Founders' Hall, London: The witty, sensitive, post-Modern building that emerged in the wake of the City's post-war orgy of destruction

Founders’ Hall — at Cloth Fair, London EC1 — is a post-Modern livery hall that is a striking home for The Worshipful Company of Founders, and a building that can teach us something about sensitive development in London. John Martin Robinson reports; photographs by Will Pryce for Country Life.

Founders’ Hall, situated in Cloth Fair in the Smithfield Conservation Area, is less than 40 years old, but already has some of the character of an established historic building. Its elevations make an intended foil to the ancient structures surrounding it. As well as being the headquarters of a medieval livery company, the building also contains income-producing flats and commercial offices.

The Founders decided to move here from their previous Victorian home in St Swithin’s Lane (near the Bank of England on Threadneedle Street) and acquired the site at the east end of the venerable Norman church of St Bartholomew the Great in 1983. The new building was completed in 1986, the date being recorded in a cast-brass foundation roundel inset into the floor of the hall staircase, in a ceremony led by the Lord Mayor of London. That plaque was cast by a member of the Founders’, a City livery company that, as do the Goldsmiths’ and Fishmongers’, still retains close working links with its original craft, including all types of metal founding, especially brass and bells.

The new livery hall was designed by the late Sam Lloyd of London architectural firm Green Lloyd and Adams. He was the grandson of the distinguished Edwardian architect Curtis Green (whose masterpiece is now the Wolseley Restaurant, Piccadilly). The firm flourished for three generations and the Founders’ Hall is its swansong, as well as an example of the City’s astonishing knack of manifesting unbroken antiquity in modern dress.

At the time of its completion, the hall was written up by the late Roderick Gradidge (Country Life, November 3, 1988), as an example of the more thoughtful post-Modern architecture then seen as a welcome departure from the bleak concrete commercial Modernism manifested in the ill-planned shopping centres and high-rise offices of the post-war decades. Gradidge enthusiastically described Founders’ Hall as ‘an excellent example of the lively courteous street architecture that all our cities so badly need’.

Gradidge’s optimism four decades ago seems rather poignant now, from the perspective of the 2020s, when destructive large-scale construction — often funded by unaccountable, off-shore interests — seems so widespread. The subtle Regency landscaping of St James’s Park has been over- shadowed by over-scaled surrounding office blocks; the views from the World Heritage site at Westminster are diminished by the high-rise construction upriver at Vauxhall/Battersea; and the City itself grows steadily taller with buildings that claim ever more massive building plots.

In the circumstances, it seems appropriate to revisit some of the schemes — such as Founders’ Hall — carried out between the 1970s and the millennium, which enhanced London and did much to reinstate the capital as a beautiful European city after wartime destruction and poor post-war planning. These three architectural conservation decades have much to teach contemporary architects, planners and bureaucrats.

In any study of architectural planning in the last third of the 20th century, the key development was the Labour government’s 1967 Civic Amenities Act, which was the brainchild of Lord Kennet and carried into effect by Richard Crossman when Minister of Housing and Local Government. It made provision for the ‘protection and improvement of buildings of architectural or historic interest and of the character areas of such interest’, as well as the preservation and planting of trees. It was this Act that introduced the need to apply for consent to demolish listed buildings, which stopped the post-war orgy of destruction of country houses and town centres at a stroke.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The main innovation of this legislation was the protection of whole townscapes by designating conservation areas, as well as individual buildings, an idea pioneered in New Orleans across the pond in the 1920s, but only taken up in England 50 years later, where it proved hugely popular.

The 1967 Act instituted a requirement that new buildings in a conservation area should enhance it, not spoil it. This transformed the architectural approach to urban planning, encouraging sensitive neighbourliness and better urban design in general.

The first conservation area in the City of London was designated in 1971 around the church of St Bartholomew the Great, Cloth Fair and the adjoining old streets and alleys. The Founders’ Hall was a new building erected on the most sensitive site in this new conservation area at the east end of St Bartholomew’s church (Fig 3). The elevations were carefully designed in relation to the setting, with tall, narrow, gabled elevations and projecting square bay windows making playful allusion to the jettied medieval houses that once lined Cloth Fair (Fig 4).

It is executed in two shades of red and brown brick, with much cast-metal detail in the form of grilles and monogrammed medallions representing the livery crafts, so it both blends into the street and expresses its purpose. It is thus a model of the type of architecture encouraged by the Civic Amenities Act: original and characterful, but respecting the surroundings by reason of scale, materials, and architectural handling.

The Founders’ Hall is characteristic of a whole series of admirable new developments in London in the 1970s and 1980s that showed understanding and respect for their historical context. These included Richmond House (for the Department of Health) in Whitehall, designed by William Whitfield, which deployed red brick and Portland stone in the manner of Norman Shaw’s New Scotland Yard and paid tribute to the lost Holbein Gate of Whitehall Palace; Paternoster Square next to St Paul’s, with ingenious spaces and vistas and careful Wren-inspired detail in brick and stone; and the Comyn Ching triangle in Seven Dials by Terry Farrell, which completed a group of 17th- and 18th-century houses around a new inner courtyard. It is difficult to think of any construction in 21st-century London that displays such knowledge and visual sophistication.

A significant role in the revival and development of London in those years was played by the GLC Historic Buildings Division (transferred to English Heritage in 1986, but subsequently emasculated and dismantled). This was a multi-disciplinary team of historians, architects and surveyors, forming part of the GLC architects’ department, which had powers of direction over local planning authorities with regard to listed buildings and conservation areas. It was active for more than 30 years, recording, reviving, controlling development and making positive design-input into whole areas, including Covent Garden, Spitalfields, Islington, Notting Hill and stretches of Bloomsbury. That these areas retain decent-looking and properly functioning mixed-use streets is due to what was achieved in those years.

The GLC Historic Buildings Division was the British equivalent of the Commission du Vieux Paris (founded in 1897), which has protected the centre of Paris for more than 100 years. As was the Paris Commission, the London Historic Buildings Committee was not only composed of elected councillors, but also had specialist advisory members who, in the 1970s, included national figures such as John Summerson, John Betjeman and Nikolaus Pevsner.

Founders’ Hall is a witness to the beneficial planning environment in the 30 years after 1967. It is also an example of enlightened private patronage on the part of a livery company. Its former premises in St Swithin’s Street did not include a hall for dinners, only offices and a parlour. The aim was to take advantage of the ground value of the previous hall, a not very distinguished building acquired in 1844 and rebuilt in 1877, and to move to a more spacious site, where it would be possible to create a more imposing home that would include a hall. This would allow for livery dinners and better display the accumulated treasures of the company, such as manuscripts, heraldry, objects, bells and, most notably, the cast bronzes of sculptors who had been members. The latter included a group by Charles Sargeant Jagger (1885–1934) given by his sister, including miniature castings for figures on his war memorials at Paddington Station and Hyde Park Corner (Fig 6).

The principal interior is the hall (Fig 1), which is ingeniously contrived on the lower ground floor, lit by oculus windows from the churchyard garden of St Bartholomew’s. It survives at medieval level, lower than the present-day street. The hall is an array of witty post-Modern tropes and allusions to metal-founding. The keystones of oculi are at the bottom, not the tops, of the windows, for example, and form bases for small bronzes silhouetted against the light (Fig 2). The ceiling is a grid of cast aluminium. There are correctly detailed Doric columns with gilt capitals and the space is exaggerated by cunningly sited mirrors, a Soane trick. The Jagger war memorials are displayed on ebonised plinths as dramatic side-pieces. A gilded wall with decorative (if not entirely genuine) heraldry of past masters forms a polychrome backdrop. The livery hall is approached via a lobby with early-20th-century stained-glass heraldry from the old hall (Fig 5).

The entrance hall at present ground level has stone panels carved with the names of all the masters from 1369 to the present day and a painting of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, which cast the company’s bell. Off the north side of the entrance hall is the parlour, also at street ground-floor level. It has a carved neo-Georgian chimneypiece and other fittings from the previous hall’s parlour (Fig 8). Some of the company’s treasures are displayed here, including the Royal Charter granted by James I in 1614 and the Grant of Arms to the Company from Clarenceux King of Arms, Robert Cooke, in 1590. The crest is an amusing example of Elizabethan heraldry, with the hands of God holding pincers and casting a brass vessel in a fiery furnace.

The spacious main staircase leads down to the livery hall and is full of light from a large bay window overlooking Cloth Fair (Fig 7). On the lower landing is a painting of Hephaestus by the artist and creator of Captain Pugwash John Ryan.

The Founders’ Company was inaugurated in 1365 when the Lord Mayor and Aldermen of London granted it livery status and enrolled its Ordinances. The 1980s hall is a living demonstration of this long company history, as well as being a witty and sensitive post-Modern architectural response to the positive planning and architectural conservation policies of the decades in which it was erected. The building is an appropriate enhancement of one of the most evocative historical streets in London.

For more details, visit www.foundersco.org.uk

A City of London walking tour: 10 centuries in one day

The City of London offers an extraordinary contrast to the visitor: it's simultaneously the oldest, most historic part of the

London has never been this quiet in 2,000 years — here's what it looks like, and what we can learn

In all of its 2,000-year history, it seems unlikely that the City of London has ever stood so silent as

The best and worst of London's bridges, from the sheer elegance of Albert Bridge to the utilitarian solidity of Wandsworth

London's bridges are integral to an appreciation of the character of the city, as well as being great feats of

-

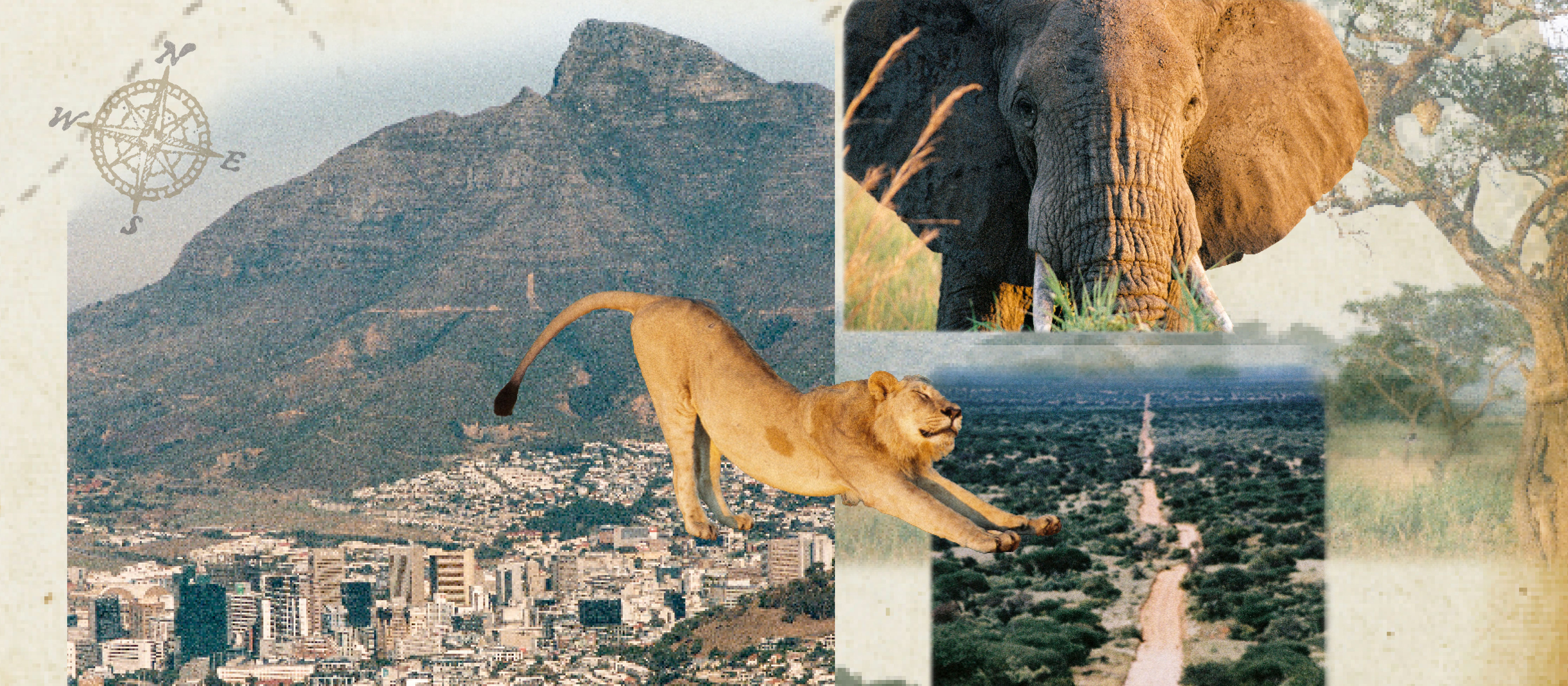

Vertigo at Victoria Falls, a sunset surrounded by lions and swimming in the Nile: A journey from Cape Town to Cairo

Vertigo at Victoria Falls, a sunset surrounded by lions and swimming in the Nile: A journey from Cape Town to CairoWhy do we travel and who inspires us to do so? Chris Wallace went in search of answers on his own epic journey the length of Africa.

By Christopher Wallace

-

A gorgeous Scottish cottage with contemporary interiors on the bonny banks of the River Tay

A gorgeous Scottish cottage with contemporary interiors on the bonny banks of the River TayCarnliath on the edge of Strathtay is a delightful family home set in sensational scenery.

By James Fisher