Fawley Court: A house by the Thames bearing the fingerprints of Wren and Wyatt

Two of Britain’s greatest-ever architects, Christopher Wren and James Wyatt, have been linked with the creation of Fawley Court.

‘Magnificent House’, ‘fine assembly’ and ‘sure we are in London’: according to Mrs Philip Lybbe Powys, these were the expressions on guests’ lips during a party at Fawley Court in 1777. Visitors to the Henley Royal Regatta will know it from the elegant fishing lodge that James Wyatt built in the form of a temple.

Ever since the Regatta began in 1839, Temple Island has marked the start of the course and, for many years, served as the Leander Enclosure. The house itself, a few strokes upstream and connected to the river by a long-water, is less familiar. Country Life is visiting it for the first time, to celebrate a nine-year campaign of restoration.

In its present form, Fawley Court was built by one Capt William Freeman, the son of Col William Freeman. The Colonel was one of the earliest settlers on the West Indian island of St Kitts, where he was granted 500 acres in 1628. Having cleared the land, he was able, by 1666, to build up an estate that boasted (according to an inventory) a dwelling house, two sugar houses, refineries, mills, furnaces, coolers, 260 sugar moulds, vinegar houses and three indigo vats, in addition to at least 20 slaves and sundry animals.

That year, however, the Freemans were dispossessed when St Kitts was seized by the French. Capt Freeman had already settled on Nevis, where he would own plantations; he also obtained a large grant on the volcanic island of Montserrat. His fortune was reinforced by a position he secured with the Royal African Company, which he advised on the market for slaves and took a commission on sales.

Then, in 1674 or 1675, he transferred his operations to London. To modern eyes, Freeman’s career does not look attractive, but we know an exceptional amount about it, because of the letter books that he kept from 1678 to 1685, edited by David Hancock and published by the London Record Society in 2002.

The 686 letters that they contain provide a rare and vivid insight into the world of a London agent, whose work combined that of a ‘seller, shipper, buyer, governor, marriage counsellor, teacher, caretaker, wine steward, outfitter, accountant, banker, funds-manager, and money-lender’ for friends, relations and business contacts in the West Indies.

By September 8, 1683, Freeman had had enough. On that day, at the end of a long business letter to Thomas Hill, Deputy Governor of St. Kitts, he sought to be excused for having neglected his correspondence, on the grounds that he had ‘lately purchased a small seate 30 miles from London on the Theames neare Henly where I now spend most of my time in order to the settlinge of myselfe, beinge resolved to withdraw from London’.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Although only in his late thirties, he had been suffering from ‘hott rumes’ and incipient blindness. A business contact on Montserrat was asked to send cedar and locustwood for use as ‘wenscott’. The old Fawley Court, a Jacobean building, was demolished.

The Wren connection

The new mansion, on a nearby site, is confidently described as ‘one of the few country houses designed by [Christopher] Wren’ by Oliver Hill and John Cornforth in the Caroline volume of the ‘English Country Houses’ series (1966).

Wren’s domestic architecture is notoriously difficult to pin down and the first reference to Wren at Fawley is in 1797, when Thomas Langley published The History and Antiquities of the Hundred of Desborough.

What can be said, however, is that Fawley arose at a time of confidence for the country house and developing ideas. England had got over the dislocation of the Civil War and overseas trade and commercial prosperity were rising, with the result that (as Charles Saumarez Smith has shown) twice as many country houses were begun in the 1680s than in the previous decade.

Several of these, like Fawley, are on the compact, square model that emerged under the Commonwealth in Thorpe Hall, was continued in Melton Constable and reached perfection in Winslow Hall and Nether Lypiatt; Wren was probably the architect of Winslow as well as Tring Manor.

Fawley’s consanguinity with this group is less obvious now than formerly, because the mullion windows were replaced with sashes in the 18th century and the dormers altered by James Wyatt in the 1770s.

However, there is nothing surprising in the client. The new house form suited mercantile aspirations, as can be seen from Honington Hall, in Warwickshire; its builder, Henry Parker, had inherited a fortune made from trading with the Levant.

Of particular interest is Eye Manor in Herefordshire, a house just five bays across, but with a rich interior: the owner, Ferdinando Gorges, known as the King of the Black Market, was another slave trader, this time from Barbados. Many of these houses, including Fawley, were built of red brick.

The plan of Fawley is symmetrical, with an entrance hall to the west and a saloon to the east of the ground floor being balanced by wings of three rooms each on either side, projecting slightly; the staircase, with barley-sugar balusters, occupies the south-west corner. The offices were contained in basement vaults.

Today, the star of the interior is the sumptuous ceiling to the saloon, a joyful explosion of foliage, fruit and birdlife, as well as a bat in a cartouche and the arms of Freeman and his wife, Elizabeth Baxter.

This appears not to have been in place for William III’s unexpected visit: the date is 1690. A hint of what the decoration may have been like in one of the upstairs rooms exists in a series of faux marble panels.

Freeman died in 1707, bequeathing Elizabeth £300 a year for life as well as plate, jewels and ‘my best coach and pair of horses’. His natural son William, ‘an infant at nurse’, got £30 a year and the rest went to his nephew John Cooke, on condition he took the name of Freeman. This John Freeman, as we should now call him, occupies an interesting position in the history of taste for the flintwork grotto that he built between Fawley Court and the Thames.

Finished in 1732, it is credited with being the earliest Gothick folly to evoke a ruined abbey or church. This is all the more remarkable, given that the inspiration was a visit to Cuper’s Gardens, Lambeth, that Freeman made with his friend Edmund Waller, a grandson of the poet, in about 1719.

Twenty-seven years earlier, the Duke of Norfolk gave a battered remnant of the Arundel Marbles to a former family servant called Boyder Cuper – it was he who founded the gardens and needed ornaments for it. In 1719, John Aubrey’s posthumous Natural History and Antiquities of Surrey lamented the ‘very ill usage’ they received from being exposed to ‘the open Air, and Folly of Passersby’. Freeman and Waller bought the statues for £75 and made a division between them.

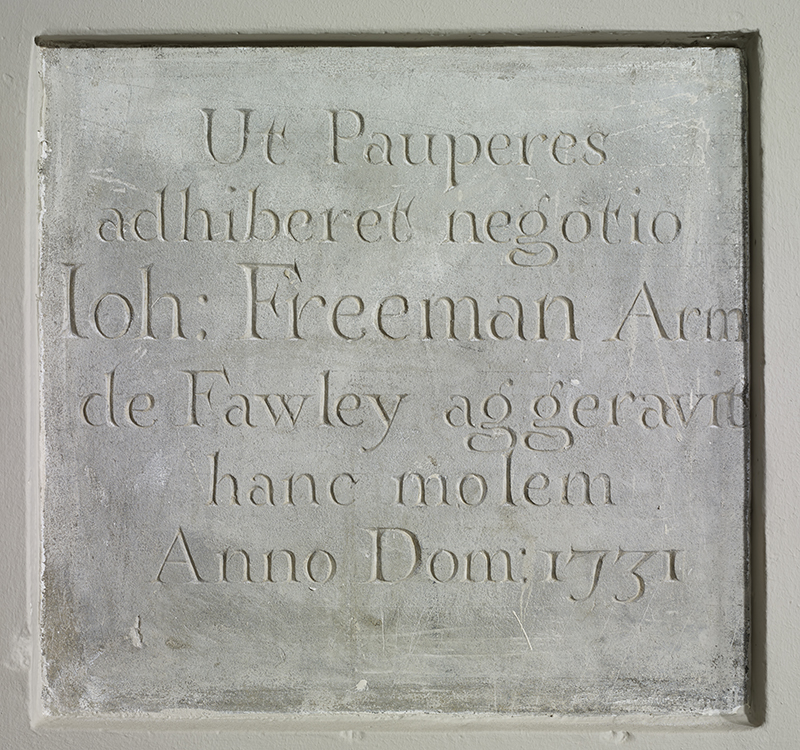

Those in Freeman’s half were displayed (still in the open air) on his folly, where some remained until the 1980s. The much-decayed Arundel Homer was acquired by the Ashmolean Museum (Michael Vickers’s ‘Mangled Statues from Pergamon,’ Country Life, November 13, 1986). A stone in the basement of Fawley declares that Freeman’s building work – unspecified in the mansion itself – was undertaken to give the poor employment.

In 1771, Freeman’s son, Sambrooke, became one of James Wyatt’s earliest country-house clients, employing him to remodel the house and build the Temple. Wyatt was only 24, but the brief was comprehensive and the budget large: £8,000. As John Martin Robinson describes in James Wyatt, Architect to George III, almost every room was transformed.

According to the diarist Mrs Philip Lybbe Powys, the ‘very fine old stucco’ saloon ceiling was spared because ‘Mr Freeman thought [it] too good to be destroyed’, but even that was improved with a new central panel of stucco – a neo-Classical pattern of vine leaves and thyrsi or Bacchic staves (presumably to replace a painting).

Parts of the Wyatt scheme survive, such as the drawing-room ceiling in an unexpectedly sharp palette of yellow, pink and green. According to Mrs Lybbe Powys, the walls of this room were hung with striped crimson damask: it was just becoming fashionable to hang pictures against stripes.

The bookcases of the library stand behind a screen of scagliola columns – a favourite Wyatt device – and the breakfast parlour contained more cases, this time for Freeman’s collection of curiosities. A relief from this rich fare was provided by the eating room, decorated in ‘a Quaker brown… I almost prefer this to any room at Fawley Court’.

Upstairs, the late Mrs Freeman’s ‘ladies’ work’ was on display in the best room, which Mrs Lybbe Powys judged ‘peculiarly fine… The dressing-room to this is prettier than ’tis possible to imagine, the most curious India paper as birds, flowers, &c., on a peagreen paper’.

Further notes of proto-Regency exoticism were added by bedrooms in the Chinese and even Persian tastes. However, one of Fawley’s most remarkable rooms does not lie in the house but in the Temple. ‘Ornamented in a very expensive manner’, it is the earliest known example of the Etruscan style in decoration, derived from the plates in Sir William Hamilton’s Collection of Engravings of Ancient Vases, published in 1766 and 1770, and Josiah Wedgwood’s Etruscan wares, being manufactured from 1768.

By 1777, Freeman had married again and could throw a party for 92 people, with card games, the ‘fine wines’ for which ‘Freeman is always famous’, hothouse fruits and ‘everything in the confectionary way… everything,’ noted a replete Mrs Lybbe Powys, ‘conducted with great ease – no bustle’.

An image of Fawley Court in the early 19th century survives in J. P. Neale’s Views of Seats, 1823: nestling in a landscape designed by Capability Brown, as boats and swans drift serenely past, the house was now stuccoed – the red of the brick walls would certainly have been too bright an accent for Brown.

The stucco was removed during a campaign of work for a Victorian owner, William Mackenzie, by, strangely, the Lancashire church architect Paley and Austin, which included a new service wing.

During the Second World, Fawley became a training school for the wireless operators of the Special Operations Executive, who shared the house with 300 cabinets from the entomological department of the Natural History Museum as well as various members of staff. In 1952, it came into the hands of the Marian Fathers, who ran it as a Catholic boarding school for the Polish community.

There was, however, almost a predestination in Fawley’s attraction for its new owner of Iranian heritage. Although the fittings of the Persian bedroom were dispersed, along with the rest of the Wyatt furniture at Fawley, in 1952, something must have spoken to her.

The house has not only been restored and decorated as a private home in a manner as bold as Wyatt’s, but the striking church of St Anne, built by the Polish architect Wladislaw Tadeusz Jeorge Jarosz using immense structural timbers, has been converted to a concert hall and event space.

After half a century of uncertainty, Fawley Court has recovered the confidence it had when the Regatta was first launched from the Temple.

The magnificent puzzle of Crichel, one of Dorset’s grandest Georgian houses

John Martin Robinson is your guide to a place where peeling away one layer only ever seems to reveal several

Credit: Simon Jauncey

Torosay Castle: The Hebridean shooting lodge that stayed in one family for 150 years

Mary Miers tells the story of a Victorian shooting lodge owned by the same family for 147 years – with

-

What should 1.5 million new homes look like?

What should 1.5 million new homes look like?The King's recent visit to Nansledan with the Prime Minister gives us a clue as to Labour's plans, but what are the benefits of traditional architecture? And can they solve a housing crisis?

By Lucy Denton

-

Having a ruff day: Kennel Club exhibition highlights the plight of vulnerable spaniel breeds

Having a ruff day: Kennel Club exhibition highlights the plight of vulnerable spaniel breedsPhotographer Melody Fisher has been travelling the UK taking photographs of ‘vulnerable’ spaniel breeds.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

High Wardington House: A warm, characterful home that shows just what can be achieved with thought, invention and humour

High Wardington House: A warm, characterful home that shows just what can be achieved with thought, invention and humourAt High Wardington House in Oxfordshire — the home of Mr and Mrs Norman Hudson — a pre-eminent country house adviser has created a home from a 300-year-old farmhouse and farmyard. Jeremy Musson explains; photography by Will Pryce for Country Life.

By Jeremy Musson

-

Sir Edwin Lutyens and the architecture of the biggest bank in the world

Sir Edwin Lutyens and the architecture of the biggest bank in the worldSir Edwin Lutyens became the de facto architect of one of Britain's biggest financial institutions, Midland Bank — then the biggest bank in the world, and now part of the HSBC. Clive Aslet looks at how it came about through his connection with Reginald McKenna.

By Clive Aslet

-

'There are architects and architects, but only one ARCHITECT': Sir Edwin Lutyens and the wartime Chancellor who helped launch his stellar career

'There are architects and architects, but only one ARCHITECT': Sir Edwin Lutyens and the wartime Chancellor who helped launch his stellar careerClive Aslet explores the relationship between Sir Edwin Lutyens and perhaps his most important private client, the politician and financier Reginald McKenna.

By Clive Aslet

-

Cath Harries — The photographer on a 15-year quest to find the most incredible doors in London

Cath Harries — The photographer on a 15-year quest to find the most incredible doors in LondonBy Toby Keel

-

The extraordinary Egyptian-style Leeds landmark hoping to become a second British Library — and they used to let sheep graze on the roof

The extraordinary Egyptian-style Leeds landmark hoping to become a second British Library — and they used to let sheep graze on the roofThe project has been awarded £10million from the Government, but will cost £70million in total.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

Art, architecture and plastic bricks at Lego House: 'It's as if the National Gallery set up easels and paints next to the masterpieces and invited you try your hand at creating a Van Gogh'

Art, architecture and plastic bricks at Lego House: 'It's as if the National Gallery set up easels and paints next to the masterpieces and invited you try your hand at creating a Van Gogh'The rural Danish town where Lego was created is dominated by the iconic toy — and at Lego House, it has a fittingly joyful site of pilgrimage. Toby Keel paid a visit.

By Toby Keel

-

Restoration House: The house in the heart of historic Rochester that housed Charles II and inspired Charles Dickens

Restoration House: The house in the heart of historic Rochester that housed Charles II and inspired Charles DickensJohn Goodall looks at Restoration House in Rochester, Kent — home of Robert Tucker and Jonathan Wilmot — and tells the tale of its remarkable salvation.

By John Goodall

-

'A glimpse of the sublime': Inside the drawing room of the 'grandest Palladian house in Ireland'

'A glimpse of the sublime': Inside the drawing room of the 'grandest Palladian house in Ireland'The redecoration of the drawing room at Russborough House in Co Wicklow, Ireland, offers a fascinating insight into the aesthetic preoccupations of Grand Tourism in the mid 18th century. John Goodall explains; photography by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

By John Goodall