The Devon Mansion that dreamt it was Versailles

An outstanding, but little-known treasure faces an uncertain future. Marcus Binney looks at the notable history of this house and issues a call for help.

Oldway Mansion is a building that fully expresses the remarkable life of its first creator, Isaac Merritt Singer. Born in 1811 at Pittstown, New York, into grinding poverty, Singer ran away from home at the age of 12, never to return. He spent 20 years as a strolling player, with a flair for gadgetry and inventions. Then, in 1851, he patented the sewing machine that bears his name. In a little over two decades, it won for him one of America’s greatest fortunes.

He was a lifelong lothario, too, fathering 24 children with different wives and mistresses, all of whom were left substantial legacies.

Singer had extravagant tastes in architecture and, when his business took off, moved to a mansion on 5th Avenue in New York. There, he owned a canary-yellow carriage drawn by nine matched horses.

Despite giving free sewing machines to clergymen’s wives, his many liaisons threatened the business and he was persuaded to move to Paris to avoid scandal. There, in 1860, he met his second wife, Isabella, by whom he had six children: Mortimer, Winnaretta, Washington, Paris, Isabelle and Franklin.

In 1870, as the Prussian army bore down on the French capital, Singer and his family left for England. By this time, he was ailing, so, hearing the air was good in the fashionable Devon resort of Torquay, bought a plot of land nearby: the Fernham estate at Paignton.

The house Singer built appears to have been substantially designed by himself with plans drawn out by a prolific local architect George Soudon Bridgman.

The history of Oldway was described by Paul Hawthorne in Oldway Mansion: historic home of the Singer family (2009). The author, together with Torquay’s recently retired mayor Gordon Oliver, has been a leading figure in the crucial battle to halt the house’s spiralling decay and find a long-term solution for the mansion.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Oldway has four show fronts that might belong to completely different houses – only the stepped and bowed back of the mansion, built in cream-coloured brick, with curvaceous iron balconies and tall French windows, remains as built for Isaac. His grand new house contained a large theatre known as the Wigwam, but his energies were soon focused on another structure, the Arena, a large rotunda opposite the main entrance completed ahead of the mansion in 1873.

This was used both for exercising horses and as a private theatre. Circuses, childrens’ parties, puppet shows and pantomimes were held here and, on New Year’s Day 1874, the children of Paignton were invited through the double doors to admire a 26ft Christmas tree decked with 1,000 presents.

When Singer died in July 1875, he stipulated that the mansion was to be finished exactly as he had planned it. This took several years. Meanwhile, his young widow (said to be the sculptor Bartholdi’s model for the Statue of Liberty) spent more time in Paris. The children, however, remained at Paignton.

They loved it so much that, when Isabella took the family in 1879 to Paris, hoping to find eligible husbands for her daughters, Mortimer, the eldest, could not bear to leave and stowed away in the postman’s cart.

This reaction anticipated a collective determination to maintain a family connection with Paignton. Paris later bought Redcliffe Towers (today, a hotel) as his residence, Washington installed himself at Streatfield House (now The Palace Hotel on the seafront) and Mortimer bought the adjoining Middlepark Villa.

Oldway, now owned by Singer’s trust, was finished in time for Paris’s coming of age in November 1888. A month of festivities saw masked balls and opera singers from the Palais Garnier. By this time, a magnificent domed conservatory had been added, linking the 1870s house to the rotunda.

In 1892, the family decided to sell Oldway Mansion at auction. When it did not reach the reserve, Mortimer and Paris bought it and Paris took over his brother’s share, moving into the house in 1897. He immediately began a grand remodelling, rivalling the opulence and scale of the palatial houses built in Newport, Rhode Island, USA, for the Vanderbilts and other magnates.

The work was done with his surveyor, J. H. Cooper. First, he refronted the south façade in a French Louis XVI style, probably using Duchêne, who was then working at Versailles on the Petit Trianon. It came with French windows and balconies painted in chaste dove grey with a white trim.

Intent on emulating Versailles, Paris com-missioned copies of the marble statues in the park and built an archway into his new cour d’honneur that was modelled directly on the Porte Sainte-Antoine at the end of Le Nôtre’s Grand Allée, complete with lions’ heads on the keystones on the arch.

The east front is more monumental, with a row of nine giant Ionic columns running the full length of the front. Such colonnades are rare in English houses as they take the light from the upper windows, although there is a parallel with Nash’s Carlton House Terrace.

Paris next remodelled his father’s north front, in 1904, removing the carriage ramp that led to a first-floor entrance and the vast conservatory. A pioneer of technology, who advised on the electrics at Sandringham, he proved himself to be ahead of his time at Oldway by installing a gym in the mansard, sometimes referred to as a squash court.

The climax came inside. The new ground-floor hall led to an astonishing staircase. Paris decided to re-create Louis XIV’s renowned lost masterpiece, the Escalier des Ambassadeurs at Versailles, designed in 1672 by Charles Le Brun, but removed by Louis XV to extend his private apartments.

Free re-creations had been attempted before, with dazzling results, as, for example, by Ludwig II in his palace at Herrenchiemsee, the Bavarian Versailles, and a century earlier in Rastrelli’s Ambassadors’ staircase in the Hermitage. The Versailles stair also offered inspiration for George Gilbert Scott’s 1860s State Stair in the Foreign Office on Whitehall.

Paris’s version was a scrupulous attempt to follow Le Brun’s original design, recorded in contemporary engravings. The Oldway staircase re-creates the luscious use of rich red marbles for walls and balustrades and inlaid floors and perspective ceilings celebrating the four continents with panache.

Paris’s painters were allowed to erect scaffolding to examine the technique of the Versailles ceilings. Both the foreshortening and the figure painting are accomplished, with figures leaning over balustrades in the Veronese manner.

All this was prompted partly by Paris’s acquisition, in 1898, of a version of one of the great icons of French art, Le Sacre de Napoléon, Jacques-Louis David’s vast painting of the Emperor crowning Joséphine in the Cathedral of Notre Dame in 1804.

David’s masterpiece was completed in 1808, but never found a permanent home during Napoleon’s life. As soon as it was finished, moreover, a group of American businessmen commissioned a new version, which David painted from memory (aided by his assistant, Georges Rouget) and only completed in 1822 when living in exile from the Bourbons in Brussels.

The second version was exhibited in the USA to great acclaim before returning to the French capital, where, in 1898, Paris outbid the French government, which had been planning to install it in Versailles. In recognition of its importance, he devised a trough beneath it, filled with water into which it could be lowered if fire broke out.

At the south end, the staircase leads into a ballroom with a parquet floor à la Versailles, with boiseries in French Régence style. The main rooms on the first floor are designed to form a continuous promenade for entertaining, with pairs of double doors connecting adjoining rooms. Access to it is through a lobby in homage to the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles.

There is evidence that, as American publisher William Randolph Hearst and others did, Paris was buying up boiseries and fittings to install at Oldway and other houses.

Soon after he embarked on his rebuilding work, Paris had an affair with one of the most glamorous women of the age: the California-born dancer Isadora Duncan. She came to stay at Oldway, but expressed a distaste for the wet English weather and the enormous, interminable dinners.

In assessing this remarkable house, it must be noted that the Singer Company was itself an adventurous patron of architecture, with a 47-storey headquarters building in New York, completed in 1908. The spectacular Singer showroom and offices in St Peters-burg in Russia survive as the House of Books, with an ornate tearoom on the ground floor.

When war broke out in 1914, Oldway was transformed into a hospital for wounded soldiers entirely financed by American money. Queen Mary was patron and visited in 1914 with the Duchess of Marlborough and other American heiresses who had married English aristocrats; Paris was in attendance.

After the hostilities, the Singer family retreated to an older house behind Oldway and the mansion was leased to a country club. Requisitioned by the RAF in the Second World War, it was bought by Paignton Council in 1946 for £46,000, with a loan from the National Health Service.

The French government bought the Sacre in 1946 and installed it at Versailles, where it now hangs in splendour. For years, it was replaced by a yellow curtain, creating the impression of a cinema, but, in 1996, a convincing Scandachrome copy of the painting – the largest of its type – was installed.

By this time, Oldway was enjoying a revival as a wedding venue and cafe, but it was not paying its way and the lease was sold to a commercial company, Akkeron, which had plans to make it into a luxury hotel. The inevitable problem was that the rooms of parade far exceeded the bedroom space and the company paid to surrender the lease.

In 2018, The Victorian Society placed the house on its Most Endangered List and the Friends of Oldway Mansion (FOM) commissioned a business plan aimed at securing a Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) grant, on the basis that new income could be generated from events, weddings, a cafe and visitors.

Commendably, the FOM was planning a series of open days, beginning last month, but council safety officers ruled that the house will not be suitable for opening until repair works have been carried out. The situation is now dire, as two outbreaks of dry rot have damaged plasterwork.

I believe that Oldway’s astonishing architecture, interiors and history have potential appeal for a much wider audience. It could become a must-see place. Some Singer furniture survives at Torquay Town Hall and could be returned, but not so much that it would inhibit use for events on a grand scale.

Rescue is dependent on recruiting American and French friends, as well as support from the HLF. The National Trust is enjoying a runaway success nearby with the opening of Greenway, the home of Agatha Christie. If the Trust were to agree to promote Oldway in its literature in return for half-price admission for its members, as it has done elsewhere, it would be a major boost. Oldway is too remarkable to lose.

Orthopaedic shoe-making: The bridge between architecture and podiatry

John Goodall meets Bill Bird, who, having studied architecture at the Bartlett, now makes orthopaedic shoes.

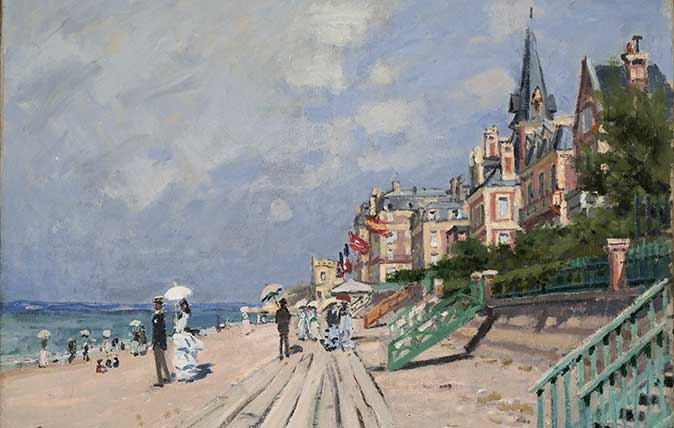

In Focus: The paintings which show Monet's genius for architecture as well as nature

Think of Monet and you think of reflections and nature, but his works included huge amounts of architecture and other

Credit: ©Paul Highnam/Country Life Picture Library

Country Life's best architecture stories of 2018: Destruction, salvation and the Gunpowder Plot

Our roster of architecture writers have brought some astonishing stories of country houses which have survived and now thrive despite

An Isle of Wight 'super-cottage' built by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert is up for sale

Queen Victoria's children and guests lived for years in the exquisitely detailed Osborne Cottage, which offers its buyer the opportunity

Osborne House: Victoria and Albert’s Italian getaway on the Isle of Wight

The search for privacy and peace encouraged Queen Victoria and Prince Albert to create an Italianate seaside villa. It offers

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Why British designers dream up the most desirable hotels

Why British designers dream up the most desirable hotelsWhen it comes to hotel design, the Brits do it best, says Giles Kime.

By Giles Kime Published

-

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication'The Great Gatsby' sold poorly the year it was published, but, in the following century, it went on to become a cornerstone of world literature.

By Carla Passino Published