Curious Questions: Why was the original Euston Station destroyed in one of the greatest acts of cultural vandalism Britain has ever seen?

One of the great masterpieces of 19th century, the original Euston Station, was built in the years after Queen Victoria came to the throne. Less than 125 years later it was razed to the ground; Martin Fone takes a look at the reasons why.

The vision of George and Robert Stephenson to link the nascent industrial hub of Birmingham with London by way of the world’s first long distance railway and thereby connecting the metropolis with the north west came a step nearer fruition in 1833. Work initially began on the London section because, as the Chairman told shareholders of the newly formed London & Birmingham Railway Company, 'the novelty and convenience of a railway contiguous to the Metropolis cannot fail to excite a general interest, and consequently to prove an early and productive source of revenue to the Company'.

The London terminus was originally a fairly rudimentary affair known as 'Euston Grove', taking its name from the Norfolk family seat of the Dukes of Grafton, Euston Hall. It consisted of a train shed with two platforms housed under sheds, one for departures and the other for arrivals, with tracks in between for carriages. The booking office and administrative offices were housed in a two-storey building connected to the departures shed.

With the London section of the railway completed, the directors invited guests on July 20, 1837, to accompany them on the hour-long journey to Boxmoor in Hertfordshire for lunch. It was not without drama, the engine derailing once and running out of water several times.

On the return journey there was an even greater disaster: the train crashed into the buffers at Euston, with the 'concussion [being] so great', according to the Bucks Herald, 'that those sitting opposite in the different carriages being thrown against each other with great violence, we are sorry to say some instances of serious injury occurred'.

Despite such an inauspicious start, by June 1838, in time for Queen Victoria’s coronation, trains were able to run from Birmingham to Rugby where stagecoaches would take passengers to Bletchley to pick up a train again. Finally, on September 17, 1838, the line was completed, allowing trains to make the 112.5 mile journey at the stately speed of 22.5 mph in 5.5 hours. Within a year there were nine return services running a day.

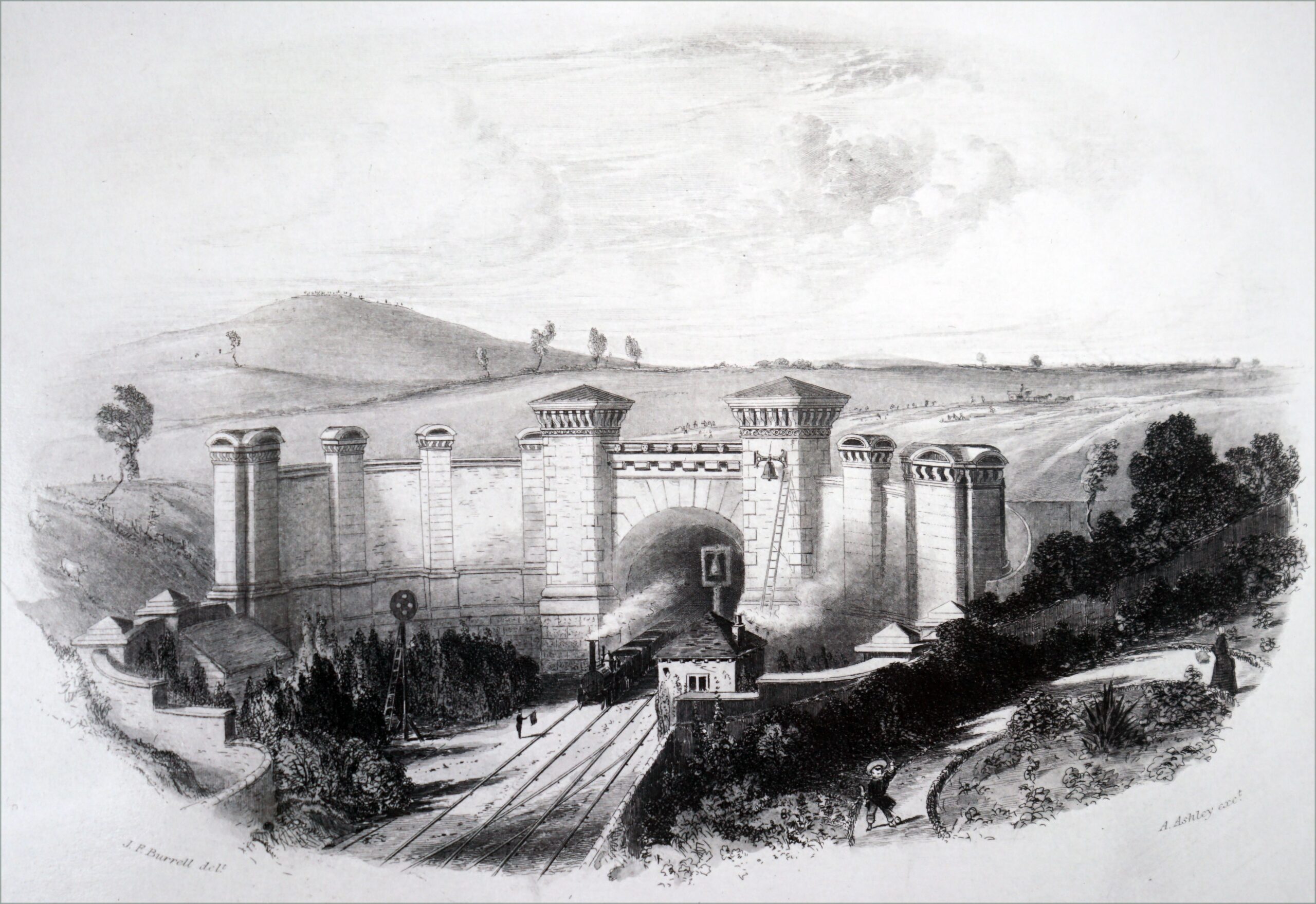

To mark the completion of the project Philip Hardwick — who had designed the original station with Charles Fox — was commissioned to design two landmark buildings, one at each of the line’s termini. Inspired by Greek classical architecture, he designed an Ionic portal building for Birmingham’s Curzon Street. It is still standing.

At the Euston end he came up with an altogether more imposing structure, somewhat out of keeping with the rest of the station, but a truly remarkable edifice: an enormous free-standing entablatured Doric propylaeum. Standing seventy feet tall, and completed in 1840, it dwarfed the capital’s other arches — by comparison, Marble Arch is just forty-five feet tall.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

It was also phenomenally expensive, costing £35,000, for which, master builder Thomas Cubbitt reckoned, an entire mainline terminus could be built. Dubbed 'The Gateway of the North' or 'Euston Arch'. And on top of that, it was not universally admired: Augustus Pugin calling it a 'Brobdignaggian absurdity', a sentiment echoed by a tourist guide to the Great Exhibition of 1851 which called it 'gigantic and very absurd'.

Either side of the propylaeum were the world’s first railway hotels which opened in 1840: the Adelaide, catering for first class passengers; and the Victoria, offering basic dormitory facilities. Such was the success of the railway that other mainline routes to the Midlands and North East were opened, emphasising the inadequacy of the existing facilities at Euston and prompting a rebuild. In 1846 the directors of the newly formed London and North Western Railway Company approached Philip Hardwick to design a waiting room for the passengers and a boardroom for the company’s directors.

What his son, Philip Charles, designed was a waiting room like no other, boasting the largest ceiling span of any building in the world at the time, 61 feet and 3 inches. Known as the Great Hall, it was surrounded by Ionic columns, sumptuously lit, with a diamond-shaped staircase at the foot of which was placed a statue of George Stephenson, walls richly decorated with carved consoles and two panels at each corner with plaster reliefs representing the key destinations from the station.

Above the entrance to the equally sumptuous Directors’ meeting room was a high-relief sculptural group, featuring Britannia accompanied by a lion, a ship, and the Arts and Sciences, while the ceiling was inspired by the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls in Rome. The walls were finished in cement to give a marble effect and the columns in red granite with white marble caps and bases.

While many used the Great Hall to while away the time before their train departed, some just came to marvel at the splendour of the architecture and others, like the writer of this anonymous piece in the Daily Mirror from 1931, sought inspiration from the quiet: 'Years ago, when hard up, I had the largest study any author had. It was the Great Hall of Euston Station, which was then set with tables and chairs; many of my early poems and stories were written there.'

The Great Hall was opened on May 27, 1849, but the constraints of the site meant that it did not line up precisely with the Arch. Worse still, as the station expanded further, to become in the words of one critic 'a ramshackle rabbit warren', the Arch could no longer be seen from Euston Road, ultimately raising questions about its future and emphasising the need for a complete rebuild of the station.

A proposed merger of Euston and St Pancras stations to create a mega-station was scotched by the advent of the Second World War but in 1959 — ironically just a few years after the Great Hall had been comprehensively restored — British Rail submitted plans to demolish all the existing buildings and completely redevelop Euston in readiness for the newly electrified West Coast main line.

The plans provoked an outcry, with focus particularly centring on the fate of the Arch. Between January 1960 and October 1961 a vigorous campaign was waged by groups including the Royal Fine Art Commission, the Georgian Society, the Victorian Society, the editor of the Architectural Review, and several backbench MPs to save Hardwick’s Arch, but, despite two discussions at Cabinet, British Rail was given the go ahead to demolish it.

Work on dismantling the Arch began on November 6, 1961. While the focus of the objectors’ campaign was on the Arch, the fate of the Great Hall, considered to be one of the finest examples of Victorian railway architecture, flew under the radar. It too was demolished.

Hardwick’s Arch, a stylised representation of which can be seen on the walls of Euston’s Victoria line station, would have stood on the southern end of what is now platforms 8 and 9. The station’s ornate iron gates, a dedicatory plaque from the Great Hall, and the statue of George Stephenson were relocated to the National Railway Museum in York while all that remains on the original site are two lodges, one of which houses the Euston Tap pub.

What happened to the remains of the Arch became clear in 1994 when architectural historian, Dan Cruickshank, discovered that some of the decorative outer stones had been used in a garden rockery, and the rest dumped into a canal off the River Lea. They have since been rescued and there are aspirations still to restore the Arch to something approaching its former glory, albeit in a different location.

The 1960s saw some of the most egregious acts of architectural vandalism, but there's no doubt that the demolition of the Hardwicks’ Euston station ranks as one of the greatest.

The immaculate restoration of the once-despised architecture of St Pancras station

'If the present popularity of the long-despised station would have struck our fathers and grandfathers as surprising, more surprises should

Britain's 100 best Railway Stations: Simon Jenkins on the gateways to our railways

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.