Curious Questions: Why did London never have a building to rival the Eiffel Tower?

England and France competed fiercely for bragging rights in the 19th and early 20th centuries — but no version of France's most famous building ever came to fruition. That wasn't for the lack of trying, though, as Martin Fone discovers.

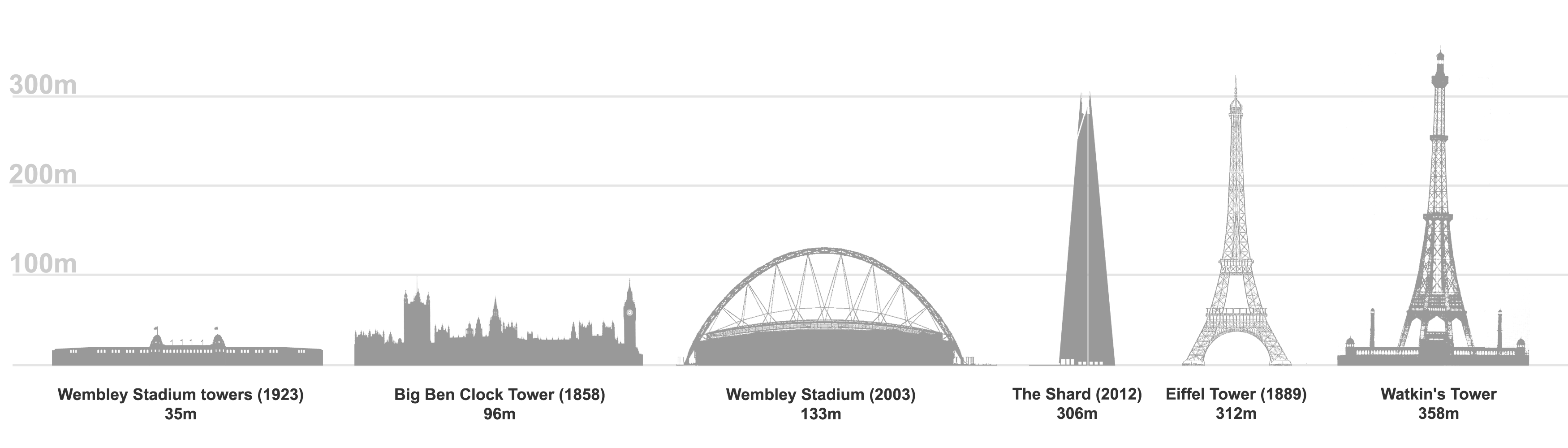

The twin towers of Wembley Stadium were an iconic symbol of English football until they were demolished in 2003 but Wembley Park would have boasted an even more impressive structure had the ambitions of railway entrepreneur and Liberal Unionist MP, Sir Edward Watkin, come to fruition. Irked by the rapturous acclaim that had greeted the opening of the Eiffel Tower, the world’s tallest structure, at the World Fair in 1889, he declared that “anything the French can do, the English can do bigger!” and laid plans to build an even taller tower.

“In another eighteen months”, Freeman’s Journal trumpeted in 1892, “London will rejoice in a New Tower of Babel, piercing the skies some 150 feet higher than the renowned Eiffel Tower of Paris. Not only will the Watkin Tower look down 150 feet on the Eiffel Tower, but it will be capable of taking up three times as many passengers at a time”.

Rather than ape the French and place it in the centre of the metropolis, Watkins chose a 280-acre plot of land that he had bought in the Wembley area, the pièce de resistance of a grandiose plan to build a new community connected to London by the Metropolitan Railway of which he just happened to be the chairman. As Sir John Betjeman observed, when telling the story of the suburbs that grew along the Metropolitan line in a 1973 TV documentary, Metro-Land, “beyond Neasden there was an unimportant hamlet where for years the Metropolitan didn’t stop. Wembley. Slushy fields and grass farms. Then out of the mist arose Sir Edward Watkin’s dream: an Eiffel Tower for London”.

The obvious designer, Gustave Eiffel, refused the commission, remarking that if he did his countrymen “would not think me so good a Frenchman as I hope I am”. Undaunted, Watkin then launched a competition in 1890 to solicit designs for the tower, which had to be at least 1,200 feet tall, topping the Eiffel Tower by some two hundred feet. A prize of five hundred guineas was offered to the winning design.

Sixty-eight designs were received from as far afield as Australia and the United States, showing a bewildering range of imagination, ingenuity, and often impracticality. Designs included a tower 2,000-feet tall looking like a multi-layered wedding cake with a working railway spiralling up it while another, described as an “aerial colony”, came with hanging vegetable gardens and a one-twelfth scale replica of the Great Pyramid on its summit. Some drew their inspiration from other notable landmarks including the spire of Bow Church in Cheapside and, appropriately as it would turn out, the Leaning Tower of Pisa.

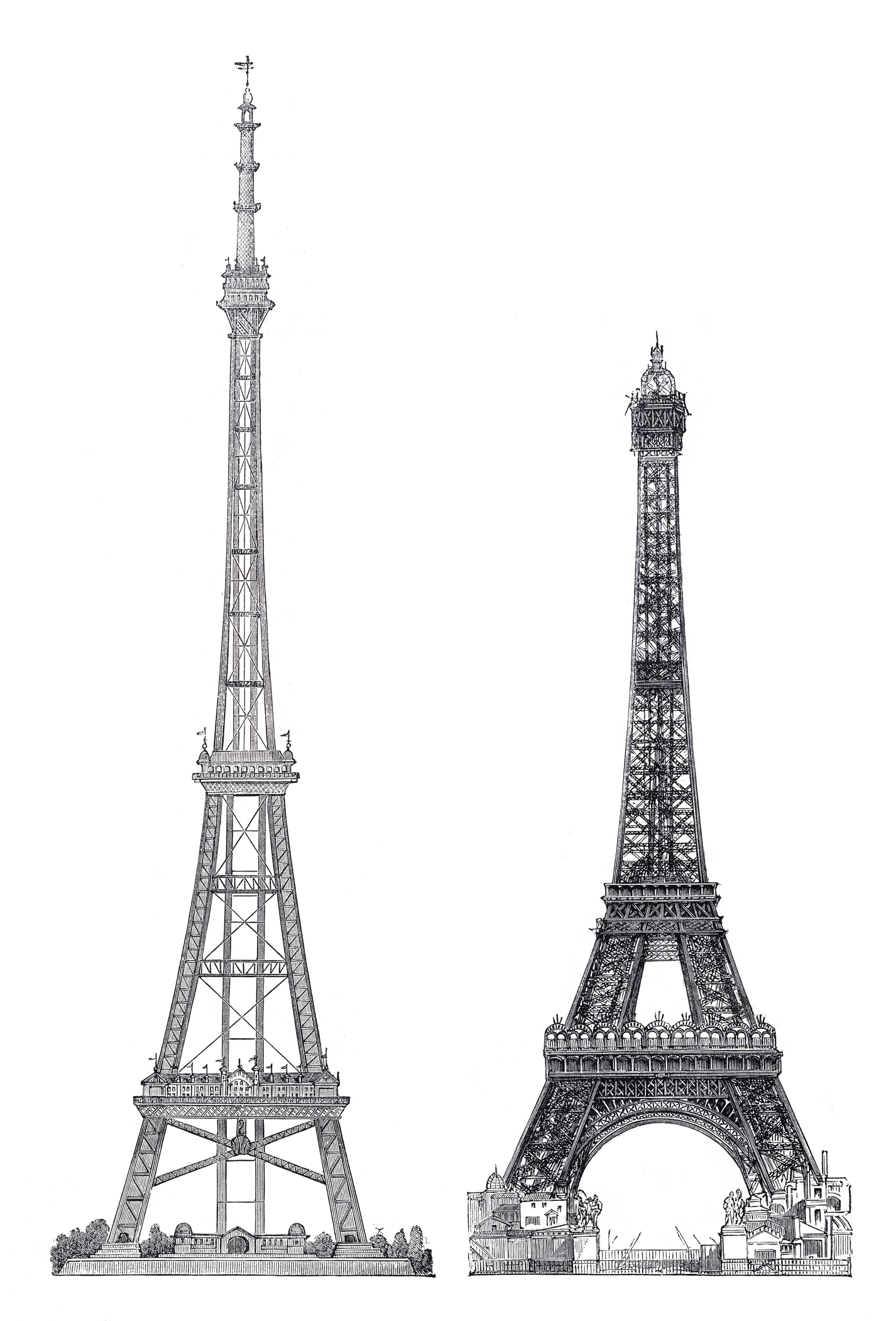

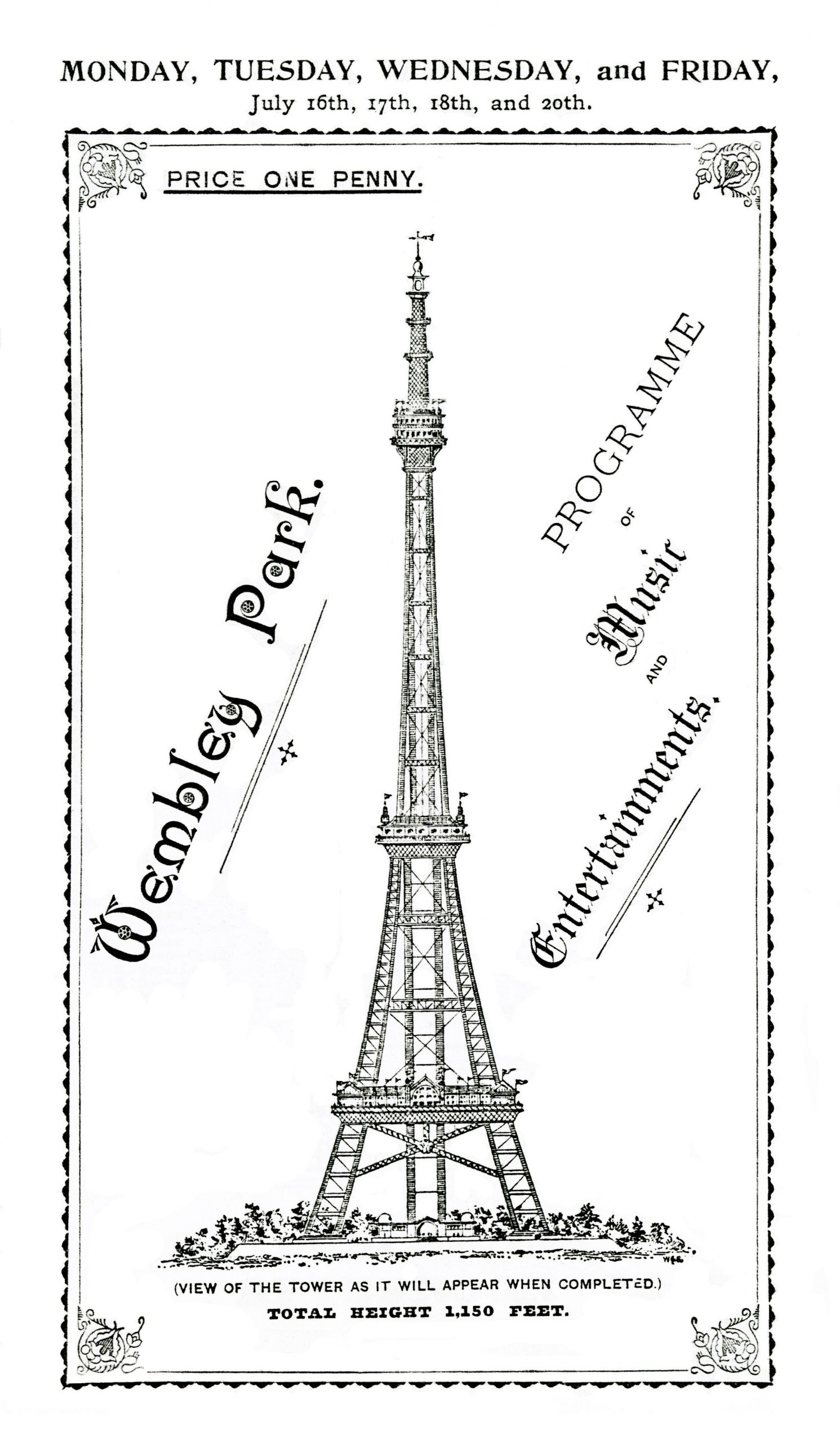

The winning design, number 37, was submitted by Stewart, McLaren, and Dunn and, in truth, looked remarkably like the Eiffel Tower, only taller at 1,150 feet, with four levels instead of three, and made of steel rather than iron.

Inside there were two observation decks containing restaurants, theatres, dancing rooms, exhibition halls, Turkish baths, and a ninety-room hotel.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The top of the tower was reached by a series of lifts where there were viewing platforms, a fresh-air sanatorium, and an astronomical observatory “because freedom from mists at that altitude would mean that the stars could be clearly photographed”.

It was nothing if not bold: if everything went to plan, the resulting creation would be so big that even as of 2023 it would still be London's tallest building.

Fired by enthusiasm for the project Watkin formed the International Tower Construction Company but investors did not match his zeal, a public subscription raised just £87,000, two-thirds of which came from his own railway company. Inevitably, this meant that the design had to be scaled back. One of consequences was that instead of being supported by eight legs, the revised design used just four, a decision that was to have ominous consequences for the structure’s viability.

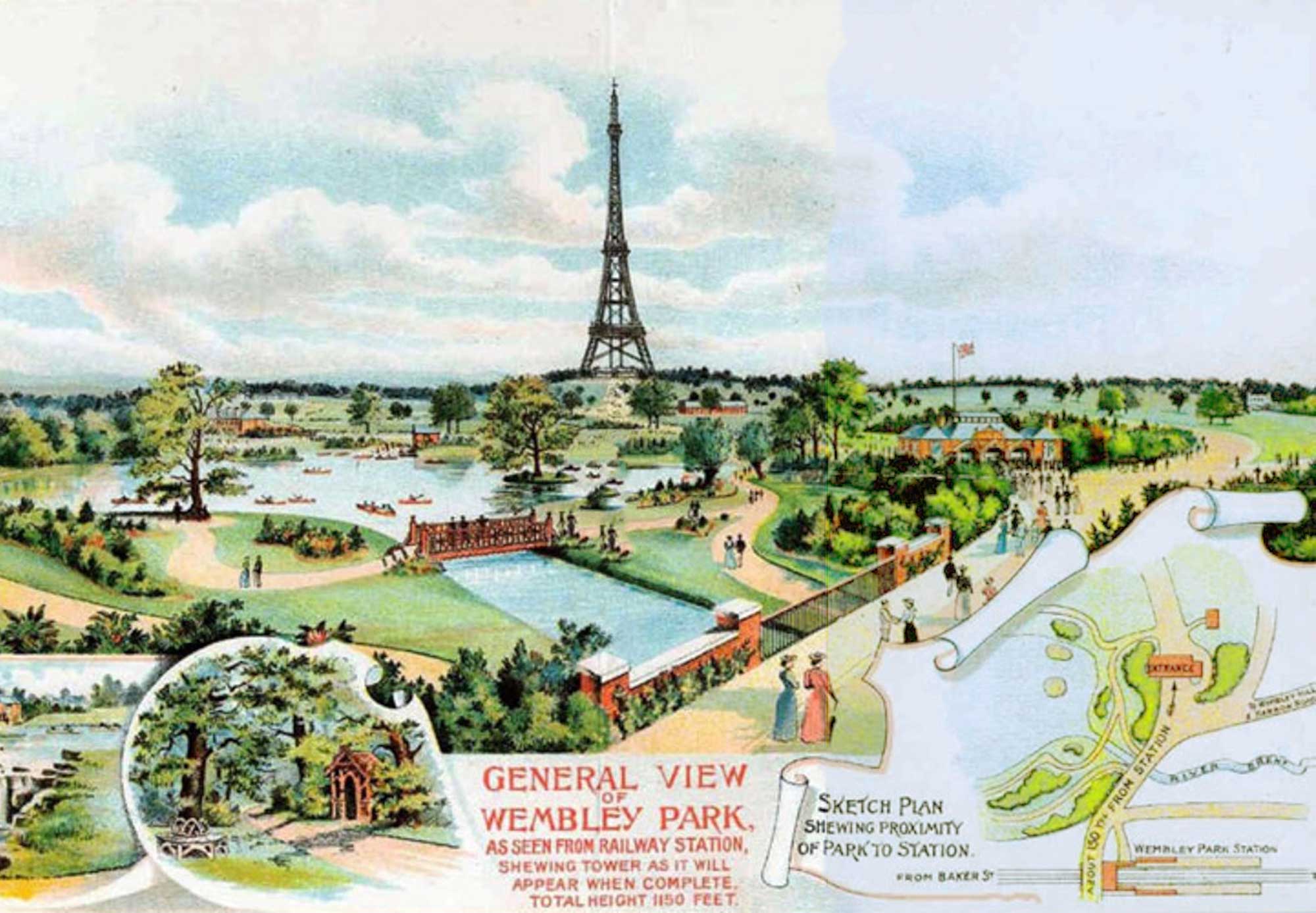

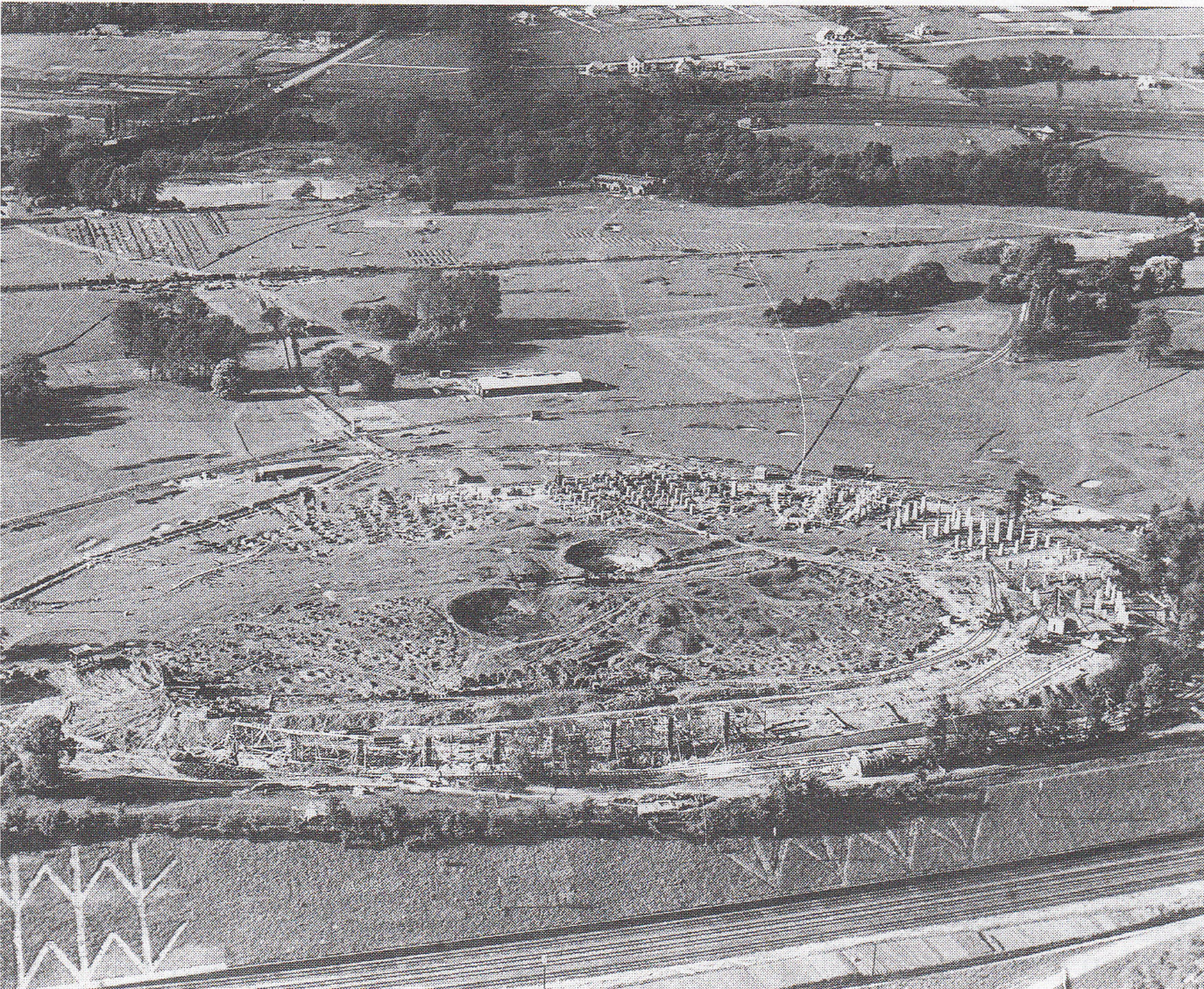

Nevertheless, the foundations were laid in 1892 and construction work began in June 1893. At the same time a park was created, boasting boating lakes, waterfalls, ornamental gardens, cricket and football pitches, and various attractions and restaurants. A new station at Wembley Park was opened on the Metropolitan line, offering a journey of just twelve minutes from Baker Street, allowing visitors to reach it with ease and boosting the railway’s revenues. Opened in May 1894 the park quickly proved a success, attracting some 100,000 visitors that year.

The tower, however, was anything but. Watkin’s company soon ran into financial problems, resulting in further compromises on the design, and, because of the marshy conditions of the site, construction work fell dramatically behind schedule. Visitors to the park had to put up with the noise of construction making it anything but a haven of peace and tranquillity and numbers dropped with only 120,000 sampling its attractions in 1895. This in turn put further pressure on the project into which Sir Edward had ploughed £100,000 of his own money.

By September 1895, against all the odds, the first stage of the tower was completed, consisting of four enormous legs supporting a platform 155 feet in the air, which was accessible by lifts. Opened to the public in 1896, it was poorly patronised with only 18,500 of the 100,000 visitors to the park that year paying to go to the top. Part of the problem was that on the outer fringes of London the tower did not offer much of a view, certainly nothing to compare with the panoramic vistas seen from the Eiffel Tower.

Watkin’s recherché and far from altruistic choice of location had done nothing to ensure the ultimate success of his project. Indeed, what was envisaged as London’s tallest structure, ten times taller than the then tallest building — St Paul’s Cathedral — quickly became an object of ridicule, dubbed variously as “Shareholders’ Dismay”, the “London Stump” and “Watkin’s Folly”.

Worse was to follow. The marshy soil on which the tower’s foundations were built coupled with the compromises in its design meant that the structure began to subside and lean dangerously. Watkin suffered a stroke and resigned his position as chairman of the Metropolitan Railway. Without his drive and vision, the project ran out of steam, the tower, still just a platform astride four legs, began to rust and deteriorate, and by 1899 the International Tower Construction Company had filed for voluntary liquidation.

In 1902, a year after Watkin’s death, the tower was declared unsafe and closed to the public and then was dismantled, the demolition team blasting the foundations to smithereens, an ignominious end to London’s rival to the Eiffel Tower.

Watkin’s ambition was no stranger to failure. His vision of linking his railway with the France via a Channel tunnel collapsed when his Anglo-French Submarine Railway Company ran out of money in 1881 after drilling tunnels from Shakespeare Cliff and Sangatte 1.2 miles and one mile long respectively.

Nevertheless, the park still attracted visitors and had put the obscure hamlet of Wembley on the map. The Tower Construction Company, now reconfigured as the Wembley Park Construction Company in 1906, concentrated on building housing in the area and the British Empire Exhibition Stadium, opened in 1923 and better known as Wembley Stadium, was built on the spot Watkin had chosen for his tower.

In 2002, when the stadium was being redeveloped, workmen found four large concrete foundations underneath the pitch, the first and last vestiges of the tower.

A nearby pub called The Watkin’s Folly commemorated his efforts, at least until it closed down in 2018. Today, only one thing remains: Watkin Road, to the east of the stadium complex, stands as a reminder of London’s Eiffel Tower that never was.

Curious Questions: Are rainbows actually circular?

Martin Fone delves into the science — and art — of the rainbow.

Credit: Getty

Curious Questions: How do you tell the difference between a British bluebell and a Spanish bluebell?

Martin Fone delves into the beautiful bluebell, one of the great sights of Spring.

Curious Questions: How does a bumblebee fly?

Scientists only discovered the humble pollinator's secret in 2005, says Martin Fone.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Curious Questions: Who invented the lawnmower?

Martin Fone delves into the history of the lawnmower and discovers a link to weaving machines.

Curious questions: Who was the first person to receive the Victoria Cross?

Martin Fone retraces the history of the order and discovers the stories of its early recipients.

Curious Questions: How fast do snowflakes travel?

Martin Fone examines the science behind snow and explores the history of snowfalls in the UK.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Curious Questions: Should you bring a snowdrop into the house?

Martin Fone delves into Britain's collective passion for Galanthus and looks at the folklore that surrounds it.

Credit: Getty Images/Image Source

Curious Questions: Why is the pork pie associated with Melton Mowbray?

Martin Fone tells the tale of a true British culinary classic: the pork pie.

Curious Questions: Did mince pies really once contain meat?

Martin Fone investigates the most traditional seasonal food of all: mince pies.

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.