Craigievar Castle, a Scottish castle full of tales of warriors and ghosts

Craigie Castle in Aberdeenshire has a rich history which we revisit here in an article from almost 115 years ago.

Our regular look back into Country Life's architecture archives has moved from Tuesday afternoons to Thursdays. Today, we turn the clock back to Peter Graham's piece from February 3, 1906, looking at Craievar Castle in Aberdeenshire. Today, Craigievar is a National Trust for Scotland property and a popular wedding venue; in Graham's time, it was still the family seat of Sir John Forbes Bart.

What power in the art of selection - for a site or a sonnet. In the days of the quarrelsome reiving lairds it was of great account to get your own abode well placed, secure for defence, handy for aggression, and Craigievar is a good example. Set in its own valley betwixt the two main ways of Dee and Don, it was easy to descend upon either - easy to retire to the castle on the hillside, whence a good look-out could he kept for an approach on any side, and where many might hesitate to follow, adventuring into a hill country, and into the heart of the clan after Craigievar had become Forbes property.

This castle was begun by others, but before its completion the lands of Craigievar were sold by John Mortymer, "with consent of Helen Symmer his spouse,'' to a brother of the famous Patrick Forbes, Bishop of Aberdeen and laird of Corse, and under him the castle grew and blossomed into the perfect example of its kind and period that it stands to this day. This brother was ''Willy the Merchant," who "made a goodlie pile merchandising at Dantzick," and, coming home with his money bags, possessed himself, in 1610, of "all and haill the lands and baronie of Craigyvar with maynes manor place towr and fortalice yrof, houses, biggings yeards orchyeards and pertinents of the samen with the corn and waulkmilns of Craigyvar miln lands multures sequels and knaveships yrof" - and a good deal besides. The lands of Craigievar "march" with those of Corse, his "old home," and the properties became united under Willy's grandson in 1681, the descendant and representative of these two important branches of the family of Forbes continuing one of the Clan chieftains. Concerning some later laird the tale runs that he was guilty of taking the slates off the older Castle of Corse in order to roof his stables at Fintray on Donside.

Corse has now parted again to a younger branch, and the old castle is quite beyond reparation; a sad pity, for it must have been a fine building, concerning the " bigging" of which there are several local tales. One of these relates that William Forbes of Corse, father of Bishop Patrick, having suffered the plundering of Highland caterans, vowed "if God spare my life, I will build a house at which thieves will need to knock before they enter." This vow he fulfilled in the erection of a strong castle, which bears the date 1581, and probably served as a model for Craigievar. It is also related that when the mason had finished his work, he washed his hands in the burn and said, ''Gin I'd he'd anither tippence I'd have been weel aft" - which shows how little money there was in Scotland at that time, and also points to the work having been done by local men.

Considered from a purely architectural point of view, Craigievar holds a foremost place amongst the examples of what is known as the fourth or L period, from the form of ground plan upon which nearly all the Scottish castles of that date - i.e., later sixteenth and seventeenth centuries - were raised up. This is of the later, more elaborate L, which gives it the tower in the re-entering angle, adding such interest of character and beauty to the whole building, from time studded entrance-door - the only one - to the bartizan or open tower on the top, surrounded by a balustraded parapet.

The castle gives one the impression of a complete, a perfect growth, rising straight and tall from the foundation rock which crops through the gravel at its base, with varying shapes of window, and flowering out in a charming richness of corralling and ornament round the turrets. These, which are two storied - gaining thereby an exceptionally elegant appearance - are a Scottish parallel to a similar blossom of the Renaissance in France. There was so much intercourse and sympathy between the two nations through all that time, and long before, that it was quite natural they should develop on the same lines in their arts, without even the flattery of imitation, although it is likely that France led an original way of suggestion.

The illustrations show how charmingly interspersed are turrets and gables, dormer windows and crow-steps, chimney-stacks, stoop-pitched roofs and parapets of bartizans. There is a true tale connected with the top of the castle and the quaint bust of a man piping on the gable-head of one window. A mason at work about the roof was walking along the parapet of the bartizan when he fell over, but was caught by his smock on the piper, and hung there until rescued from above. So is ornament sometimes well justified of her designers! The castle was doubtless originally slated with the old stone slabs, but it was reroofed about 1826, when it was to receive "a complete new roof of best Memel timber and covered with Fondland slates put on with copper nails, and to have ridges and values of lead in place of stone and slate as at present."

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The whole castle is "harled" or rough-cast in a fainter shade of the red gravel of the district, matching the mouldings and parapet of reddish granite softened with age, whereas the ornaments and gargoyles which jut out are of sandstone, and have in some cases yielded to the long stress of weather and fallen off. One such lies below, a quaint fellow, hugging his legs in his arms, or a pair of whisky bottles, say the irreverent; others still standing out from the ornament of masks and heraldic beasts among the corbelling show, when the sun makes clear tile detail, designs of thistles, twisted rope ornament, or scales worked round them.

"There was originally," wrote Sir Andrew Leith Hay in 1847, "a paved courtyard in front, enclosing stables and offices, which was surrounded by a strong and very thick wall with ramparts flanked with turrets. Only one portion of this barrier now remains, and trees of considerable size, rooted in its masonry, have usurped the station formerly occupied by the defenders of the formidable stronghold." And those trees are still growing up through the wall, where the thick ivy covers the marks of the chimney of the original kitchen which had evidently been without the main building. Very few castles of that period have any of the surround wall left standing, and here it is exceedingly picturesque on the west, between the castle and the rising ground, covered with ivy, crowned with sycamore, ash, and a gean (wild cherry) tree that flames in the autumn against the slated turret which stands complete at the southern end of the wall. Steps still lead up through the gateway that was once the only approach to the castle, where on either side in the thickness of the wall are recesses with apertures for outlook and defence.

Behind the one door, which gives entrance to the castle, hangs still the old iron yet or gate, in strength of interlaced bars with its great bolts and lock. The kitchen and cellars, which are only partially underground, are all vaulted; the well under the kitchen, in which a fiddler is reported to have been drowned, is no longer open:

"If you sit there on a windy day You'll hear the fiddler begin to play."

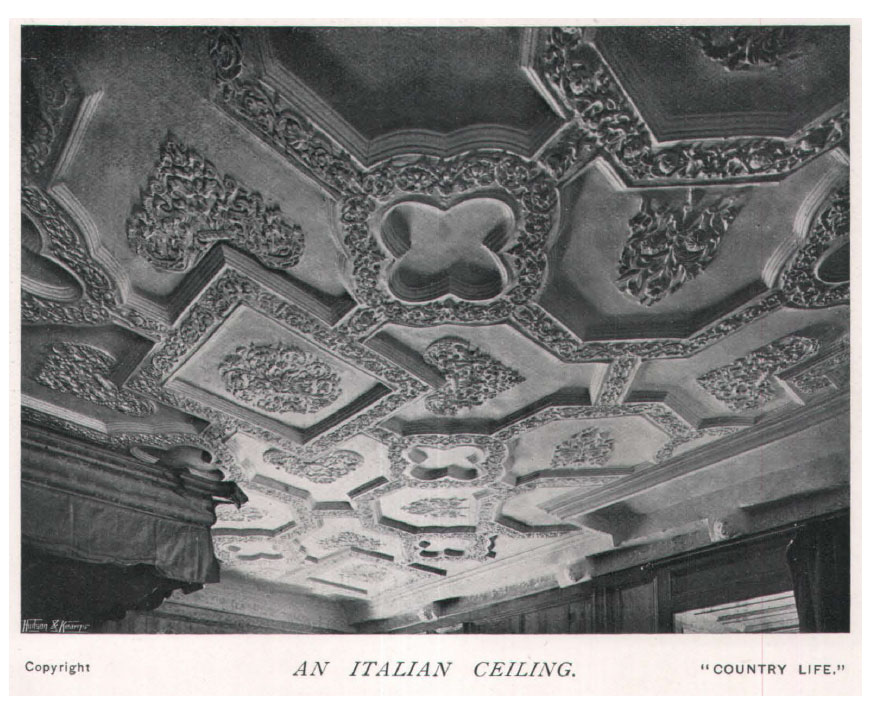

Up the wide, straight bit of stair known, as a scale-stair, the great hall is reached. "Willy the Merchant" had done more than make money in those far travels of his; he must have acquired more taste than many of the more stay-at-home Aberdeenshire lairds of that time possessed, for he was not content with a strong tower of shelter and defence - it must also be a beautiful home; so he "plastered it very curiously," summoning that band of Italian craftsmen who have left a trail of beauty all down the East Coast of Scotland.

They must have spent a long time here, for among all the houses where these men are known to have worked there seems to be no other where so many rooms were decorated. For the most part folk were content with the decoration of the principal rooms, and, perhaps, one or two guestrooms; but here ornament is lavished on bedrooms, through several landings off the winding stairs, and with such richness of effort, such variety of design, in the larger rooms flowing with fancy, quaint or really beautiful, prim or grotesquely merry, in the smaller rooms using simpler designs of flatter geometrical banding.

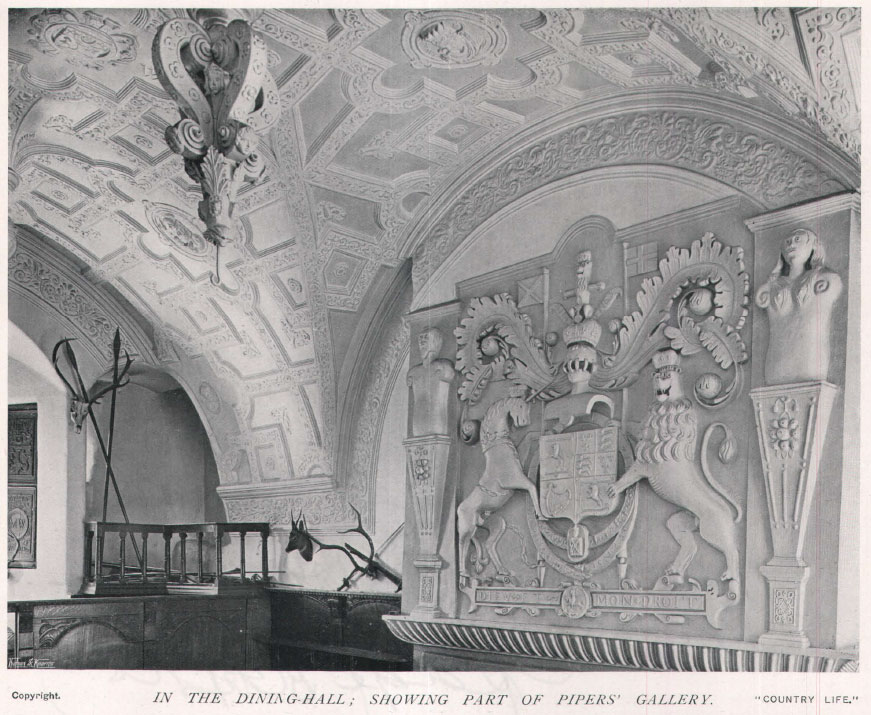

The great hall is evidently a hall of heroes, for here are "David Rex," with his harp, '' Josue Dux," with a glaive, "Hector of Troy," sadly lacking in neck, and "Ajax." A great favourite is "Alessauder Magnas," who is repeated in other rooms. This hall occupies the whole arm of the L, and has thus windows on all sides, the east one, however, only showing over the carved oak screen which runs right across that end, and upon which rest the pipers' galleries on the two sides, which are surmised to have been formerly connected in the thickness of the wall until this was cut away when the windows were enlarged to their present size. That is perhaps the only conspicuous alteration that has ever been made to Craigievar, which remains the more valuable in having suffered so strangely little at the hands of improver or restorer.

The hall is still the living-room of its first days, with great fireplace where logs roared on the hearth, and where as lately as 1842 fresh rushes were daily strewn on the boarded floor. In the stone wall inside the great chimney up 80ft. of which you can look to the sky, is a recess known as the salt-box - where the salt was kept dry and probably ravingly in the days when it was costly. The hall itself is stone vaulted, with the plaster ceiling laid upon it with much cunning; but over the fireplace upon wood is rougher work in bold relief of some composition, where are the Royal Arms with Scotland quartered twice, the supporters flanked by quaint terminal figures of Adam and Eve.

On the ceiling amidst the heroes are the arms of William Forbes and of Margaret Udward his wife, whose united initials appear in many places in the plaster - work through the castle, with dates varying from 1610 to 1626. Above the east window, and round the nearest bosses, are various writings - "LUX MEA CHRISTUS" - ''POST TENEBRAS SPERO LUCEM" - "DEUS LUMINA" - "VIRTUS VIVAT POST FUNERA." These may all he ascribed to William, who was, doubtless, a godly man. But a motto of more worldly significance finds place also on the castle walls in the words "DOE NOT WAKEN SLEIPING DOGS," coupled with the initials of his grandson, known as the Red Sir John, and origin of the saying "I'm a Craigievar man - wha dour meddle wi' me.''

The hall is wainscoted with oak; the other rooms are all of later panelling, mostly done in the native red pine, and it is not very long since the beds in some of them were just two-storey bunks against the wall, which was of rough stone, or hung with strange painted cotton that moved mysteriously in the wind and firelight. Several box-beds still exist. Between the withdrawing-room and a very small one, called the Prophet's Chamber, there have been two doors, between which it is narrated that offenders and captives were placed for judgment before being consigned to the dungeon, where food was let down to them through a trap-door. From the scale-stair a winding stair runs right up through the building, finally giving access to the smaller bartizan on the east side. The larger one is reached by a short stair from the fifth floor, and another circular stair runs through three storeys in the north-west corner straight in to the great hall.

As to the men who lived in this beautiful stronghold, "Willy" was succeeded by his son, who was made a baronet of Nova Scotia in 1630, but later, "affected by the epidemical madness of the period, rashly engaged in the cause of the covenant," and is repeatedly spoken of as a ''main covenanter" or "Cragyvar that famous man," sometimes "that famous oppressor!" He filled various posts under the Parliament, but he repented him of this covenanting zeal, and is said to have died brokenhearted because his party stripped him of all the goods he desired to carry back to his King. His son, the Red Sir John, is described as a man of great energy of character, who did much to retrieve the fortunes of his house. The Craigievar men were not all and entirely fighters, and even at home occupied themselves with other things than upholding feuds with their clan foes and holding their '' courts of baronie," as more than one of them is said to have used his pen to poetic purpose, notably an Alexander, born in 1700, who is called "a child of an ardent spirit, and of so strong and beautiful a genius that in the twelfth year of his age he has wrote poems which are read of all with admiration."

Which of these old-time indwellers is it whose spirit will not be wholly parted from the place, and returns somewhiles to wander gently through the rooms, silently and invisibly opening doors? The real "ghost" of a man murdered in his bed for revenge and flung out of a window is of the kind that may terrify, but there is something touching in the thought of this gentle home-comer. How gladly would one hold one's self, if one might, in a silence of spirits to be led by such a guide into a truer vision of the romance which is the very soul of such a place, and of which a whisper may sometimes be captured, when the night wind sounds round the turrets among the tree-tops.

The Channel Tunnel's centuries-long shift from fear of 'foreign hordes' who'd 'deface the countryside' to our magnificent link to the Continent

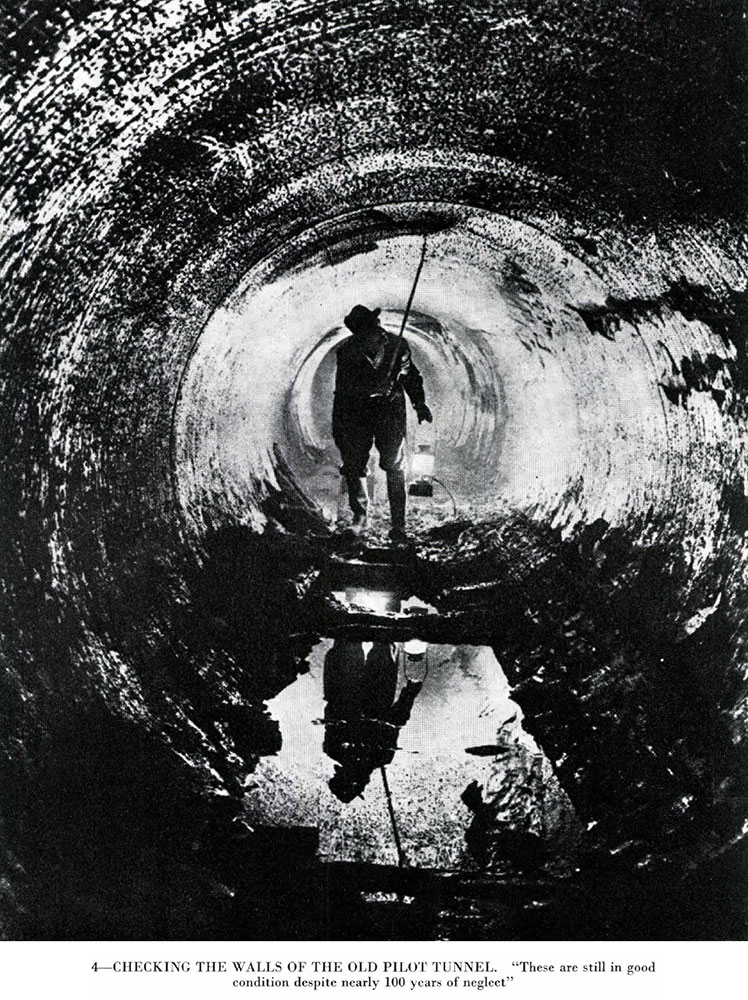

This week's architecture archive looks at the two centuries' worth of plans which eventually resulted in the Channel Tunnel between

Houghton Hall, Norfolk - II: A Seat of the Marquess of Cholmondeley by John Cornforth

From the Country Life Archive: John Cornforth discusses how the architectural decoration of the piano nobile at Houghton is complemented

Riding on Status: The Stables at Houghton by Giles Worsley

From the Country Life Archive: Sir Robert Walpole was a distinguished politician and a keen architectural patron, but when he

The immaculate restoration of the once-despised architecture of St Pancras station

'If the present popularity of the long-despised station would have struck our fathers and grandfathers as surprising, more surprises should

The oldest house in Britain — and how we were able to tell it apart from the other contenders

There are many nominations for the oldest home in Britain — in this piece from the Country Life archive, John Goodall

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Jungle temples, pet snakes and the most expensive car in the world: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 14, 2025

Jungle temples, pet snakes and the most expensive car in the world: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 14, 2025Mondays's quiz tests your knowledge on English kings, astronomy and fashion.

By James Fisher Published

-

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'A party barn is the ultimate good-time utopia, devoid of the toil of a home gym or the practicalities of a home office. Modern efforts are a world away from the draughty, hay-bales-and-a-hi-fi set-up of yesteryear.

By Annabel Dixon Published