The photographs (and photographers) who shaped the English country house style from the 1900s up to today

To coincide with the publication of his new book illustrated from the archives of Country Life, 'English House Style', John Goodall considers the long tradition of the magazine’s peerless interior photography.

To receive a Country Life photographer into your house in about 1900 was to invite disruption. Indeed, the experience was described by one member of the family at Audley End in 1926 as being ‘worse than burglars’.

That’s partly because the magazine’s editorial team, eager to illustrate the history of interior style, began to demand that furniture in a room matched the period of its architecture.

As a result, the bric-a-brac of late-Victorian and Edwardian life needed to be stripped away. Alternatively, if a house was inadequately furnished, appropriate chairs and tables might be moved from room to room to illustrate successive photographs.

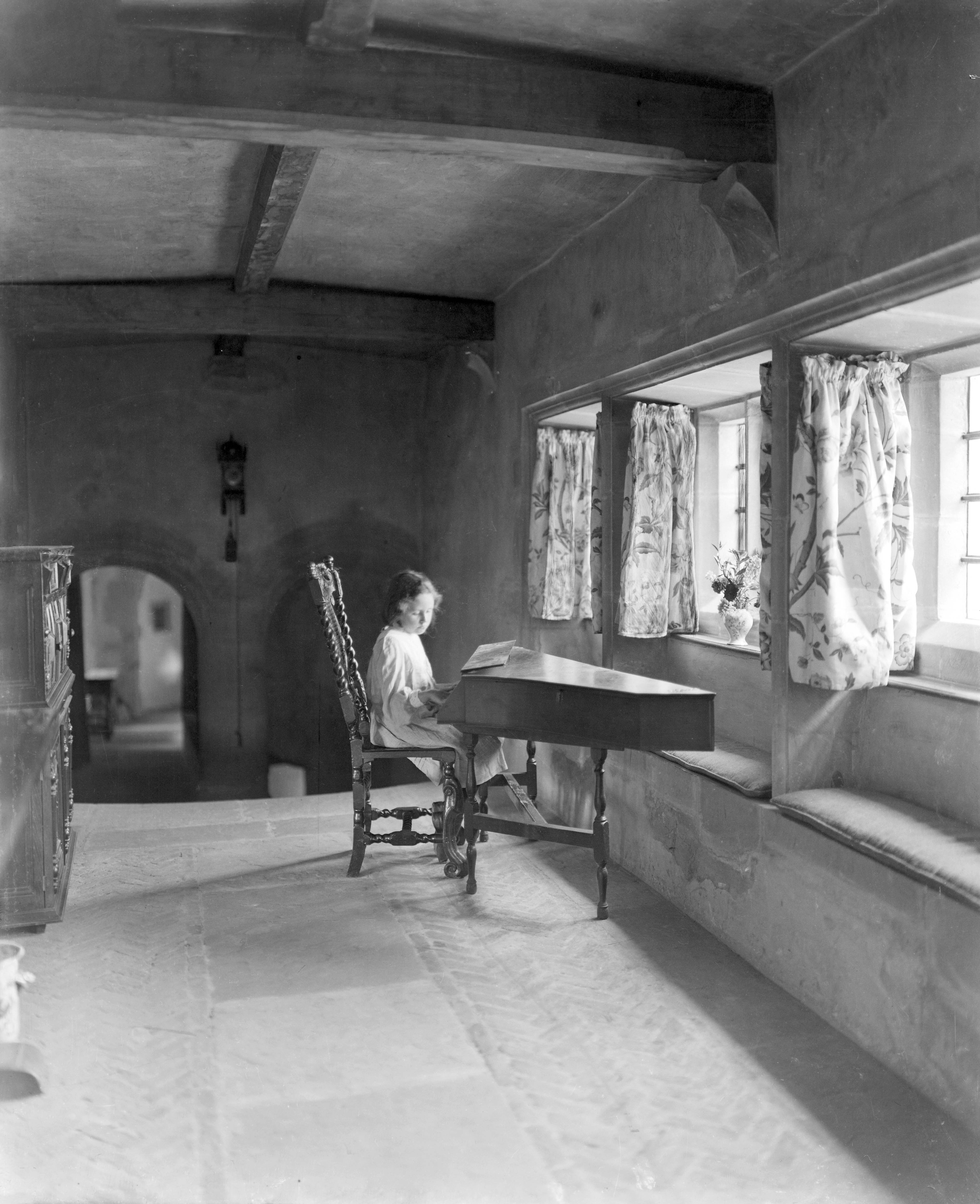

No less disruptive, however, was the fact that photographers needed natural light to work. One Scottish chatelaine reputedly rounded a corner of her drive and was horrified by the sight of every mirror in the house laid out on the front lawn to reflect light indoors.

With the capacity for very long exposures, the quantity of light was less of a problem than the need for it to be diffused. Concentrations of light risked burning out sections of a photograph and this, in turn, demanded that windows be masked.

The aesthetic ideal was of a 17th-century Dutch Old master painting, serene and timeless.

Such was the success of this photography that – despite being meticulously contrived – it has defined the popular image of the English country house. It also, as a consequence, often informs the modern arrangement of these buildings and their interiors.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Country Life photographers still work in the aesthetic traditions of their predecessors, photographing interiors with natural light. Digital photography makes it possible to obtain the same effects without such levels of disruption, but the results distinguish the magazine’s pictures from any other.

This book draws together historic and modern photographs from the archive into an over-arching history of English interior style from the Middle Ages to the present day. At the present moment, when photography has been democratised to such an astonishing extent, its contents are a powerful reminder of what the professional’s eye can achieve above and beyond that of the amateur.

It proves that Country Life’s photographers continue to produce extraordinary images that rival, or even exceed, those of their predecessors.

Stirling Castle: Renaissance of a Royal Palace

It was within sight of Stirling Castle that two of the most famous Scottish victories over the English were won.

Traquair House: The Tightrope of Power by John Goodall

A great Lowland house in Peebleshire offers a fascinating insight into the eventful history of its owning family. John Goodall

The Country House Library: Why these rooms and their collections need to be taken much more seriously

A new account of the country-house library will compel us all to reassess these rooms and their collections, says John

Chenies Manor, Buckinghamshire: The Tudor estate that encompasses the ancient oak tree beneath which Elizabeth I lost a piece of jewellery

This Tudor house was the unlikely venue for the first meeting of the founding group of The Arts Society. John

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.