Columbine Hall: A medieval, moated manor house that's been transformed into a perfect country home

Columbine Hall is a medieval moated manor house, lovingly re-imagined as the beau idéal of an English country home. Jeremy Musson reports on this remarkable achievement, with photographs by Paul Highnam.

Along, L-shaped timber-frame house, set within a wide moat, Columbine Hall is a very English and beguiling house. From its late-14th-century origins, it has evolved, as manors do, modestly adjusting and adapting over time. But the building’s medieval character still predominates, the gabled form reflected in the encircling water.

Columbine Hall has been subject to a tactful and well-informed programme of restoration since the house and 30 acres were acquired by Hew Stevenson, formerly chairman of a large group of regional newspapers, and his wife, Leslie Geddes-Brown, a writer with a long association with Country Life, not least as a gardening correspondent.

They have worked to provide a fitting degree of modern comfort, as well as bringing out the best of the house’s historic character. In 2014, for example, modern cement render that was damaging the ancient timbers was entirely replaced by traditional lime.

It is not only the house that has been transformed; the surrounding gardens, outbuildings and landscape have all received careful attention. The large timber-frame barn, its walls painted in a terracotta wash, is now used as a function room and for wedding receptions; the next-door gig house has been converted into a comfortable cottage.

Most impressive are the changes to the farm office overlooking the moat on the north side. A workaday 1960s brick box now reads like an elegant late-17th-century building with sash windows and a jaunty cupola. Within the moated site itself, a new semi-formal garden has been created, giving the house a fitting background and frame.

An intriguing survival from the late Middle Ages, Columbine Hall documents a particular strand of interest in British history and the nature of its rural domestic architecture, long associated with publications such as Country Life. Indeed, it could be argued that this interest has shaped the British idea of architectural heritage throughout the 20th century, as well as the nature of influential institutions, such as the National Trust.

Within the house, renovations to the interiors have been tempered by the owners’ interest in family history and by their collections of antiques. Displays reveal a confidence about the mixing of formal and informal and a keen sense of the importance of colour, texture and patina. This same confidence is found in the gardens around the house — in short, Columbine Hall is an expression of the civilised pleasures of a well-ordered and managed country retreat.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The hall’s manorial records are some of the best preserved for any manor of late-medieval Suffolk. Held by the Suffolk Record Office, they have been researched by Mr Stevenson to identify the owners and occupiers. He has published their stories, together with accounts of later residents, including wartime evacuees, in Columbine Hall: the Story of a House and its Transformation (Dove Books, 2018).

The moated site is likely to be considerably older than the house and there must have been an older manor. However, the jettied timber-frame ranges we see today are clearly late 14th century in character and were probably erected by Robert Hotot, a prominent Suffolk judge who held the property from 1377 until his death in about 1402. The original house, which stood on the north-west corner of the moated site, was perhaps nearly double the size of the building today.

What has survived was probably the gatehouse range, through which the main courtyard was approached (across a bridge) via an opening still visible in the wall. A distinct range to the east contained the great hall and solar, perhaps linked to the north range.

Anne, the granddaughter of original owner Hotot, was the sole heiress and married James Tyrrell, a younger son of Sir James Tyrrell of Gipping Hall, supposed murderer of the Princes in the Tower.

The house remained with the Tyrrells until 1557, when its mortgagee, London merchant Thomas Stanbridge, acquired it. He sold the property to another Londoner, John Gardiner, in 1559, and it is suggested he reduced the house by demolishing the great hall, as well as the medieval kitchen and service range.

Although the hall range may have come down later, these alterations point to an updating of accommodation. The brick chimney serving four hearths must have been inserted at about this time, as well as the two-storey porch that sits in the southwest corner of the approach court.

The Gardiners seem to have arranged to leave the manor to William, a younger son of Henry Carey, 1st Baron Hunsdon, but, after a complex legal battle, it came into the hands of his brother, Sir Robert Carey (who recorded the tiresome litigation in his memoir). Sir Robert leased the manor to one Giles Keble and, in 1608, Columbine Hall was acquired by Sir John Poley, a retired soldier. It is likely that Poley installed the main staircase and the carved overmantel in the north-west bedroom.

The house remained with the Poleys, passing to Sir John’s son and then his cousin, Lady Gipps, together with nearby Badley Hall. It was sold in 1735 to John Crowley, who hailed from a family of wealthy iron merchants.

A large-scale estate map, commissioned by Crowley in 1741, now hangs in the staircase hall. It shows the house already reduced to its L-shaped plan, but before it was slightly extended to the east.

On Crowley’s death in 1754, his property was inherited by his sister, the Countess of Ashburnham, and the hall became one of many tenant farms on their extensive estates. For much of the 19th century, it was tenanted by the Boby family. There were some alterations in the 1820s, including creating a new parlour and master bedroom above, on the east side of the house, and a hall passage to add a spacious link between the two ends of the house. The property was sold freehold in 1918 and remained a working farm for the next eight decades.

When the current owners acquired the hall in 1993, it had barely been altered in four decades and had stood empty for seven years. There were acres of concrete hardstanding, many farm buildings of jarring redbrick and asbestos, various Nissen huts and six rusting grain silos. The new owners joked that the only way to tackle this ‘project’ was to imagine they had been left it unexpectedly and could not sell it, and so were forced to ask themselves how could they make it work.

Miss Geddes-Brown’s work, as Arts correspondent on The Sunday Times and deputy editor of Country Life and World of Interiors, had given her considerable exposure to the best of English interiors during this period of re-discovery of the English look. After repairs, the interiors were transformed with the assistance of Melvyn Smith, whose work on his own house, Strines Hall in Derbyshire, had impressed her. He helped the new owners reveal three 16th-century brick hearths, reconstructing the upper part of the one in the dining room.

Mr Smith’s particular talent is the invention of interiors. He fitted out the 1820s drawing room with painted MDF panelling in a 1710 style, complete with overmantel and antique Delft tiles around the fireplace.

He also created the clock tower (‘a long way after Wren’) atop the old farm office, transforming a nondescript building into a eyecatcher within the garden vista.

In the first-floor rooms, wide elm floorboards were rediscovered and the timber roof structure revealed, together with the remains of blocked mullion windows and a 14th-century internal doorcase. As well as new, comfortable bedrooms, a first-floor library-sitting room was created, with shelves that look Georgian, but are actually made of MDF, with little enamel shelf numbers taken from an old French clock.

The northern end of the main range contains a light, double-height writing office, where Miss Geddes-Brown works on her many garden and interiors books and Mr Stevenson on his publications and genealogical research. One of the original, late-14th-century, mullioned windows are set in the east face of this room.

The kitchen on the western range eschews the ultra-modern. This is an English country kitchen in every sense, its bare walls unspoiled by modern units. The interior is composed like a Dutch still life and overflows with produce from the kitchen gardens. It connects to an intimate dining room on the south-west corner of the house, which provides a perfect setting for part of a cherished collection of oak furniture inherited from Miss Geddes-Brown’s parents. The character of this room and the adjoining moat room are constantly changing according to the time of day and weather, as they register the intensity and tone of light reflected up from the moat.

Historic portraits hung throughout the house relate to both its history and that of its new owners, featuring Stevensons, Garretts and Runcimans especially. Relative newcomers to the house, they sit here happily, providing a rich seam of visual and human historical reference. The hall has a fine 1816 portrait of James Stevenson by Andrew Henderson of Glasgow; he was the founder of the family newspaper business and an entrepreneur who revived a chemical factory on Tyneside. A John Pettie portrait of Newson Garrett shows the man who built nearby Snape Maltings and was father to even more famous daughters: the suffragist and women’s rights campaigner Millicent Fawcett and pioneering physician and surgeon Elizabeth Garrett Anderson.

The garden around the house resonates with the same appreciation of history and feeling for aesthetic discipline. It was mostly laid out in 1993–94 by designer George Carter, who has worked on historic sites such as Burghley House and the Royal Hospital, Chelsea.

To enhance the sense of arrival at the hall, Mr Carter planted yew hedging to stagger the approach. He also suggested the idea of treating the moat effectively as a ha-ha, dividing the internal space through hedges and planting, creating an echo of the intimacy of rooms in the house. There is an allée of pleached hornbeam aligned to a window from the drawing room and a series of poetic walks create vistas and views orientated towards the house and out over the landscape beyond.

The overall effect is contemplative and architectural, managing to convey a sense of poetry and allowing for a consideration of the attractions of rural life. There is also a hint of the Italian, with Miss Geddes-Brown mentioning early-17th-century La Gamberaia, near Florence, as an influence, where designers ‘try and have a bit of everything in a few acres’.

More than 1,000 native English trees have been planted around the fields of the site, creating shelterbelts and groups of field trees to give the impression of the lost park.

Now in a good state of maturity, the garden is maintained by Kate Elliott, who arrived at Columbine more than 20 years ago. The large walled vegetable garden was inspired by the Château de Bosmelet in Normandy and is planted out by colour. Outside the moat, a bog garden planted with ferns and wild garlic winds its way along a former ditch, now a running stream. A Mediterranean garden is filled with drought-tolerant plants such as lavender, cistus, eucalyptus and ivy.

Together, house and garden express a sense of history, an attention to detail and an aesthetic balance. Reflecting the knowledge and experience of their owners, they contain an almost literary evocation of other family houses, encompassing their histories and stories. This seems only fitting in what might be called a ‘well-read’ house and which is certainly a well loved one.

For more information, visit www.columbinehall.co.uk

Things we never knew you could do with garlic... from jam to vodka

Leslie Geddes-Brown has discovered all manner of things to do with garlic.

London has never been this quiet in 2,000 years — here's what it looks like, and what we can learn

In all of its 2,000-year history, it seems unlikely that the City of London has ever stood so silent as

Rosie and Jim: 'The robin has probably been here for years; I’ve only just noticed him. He’s probably as curious as I am'

Country Life's Rosie Paterson and James Fisher are — as we all are — in isolation, entirely alone except for

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Mary Greene

-

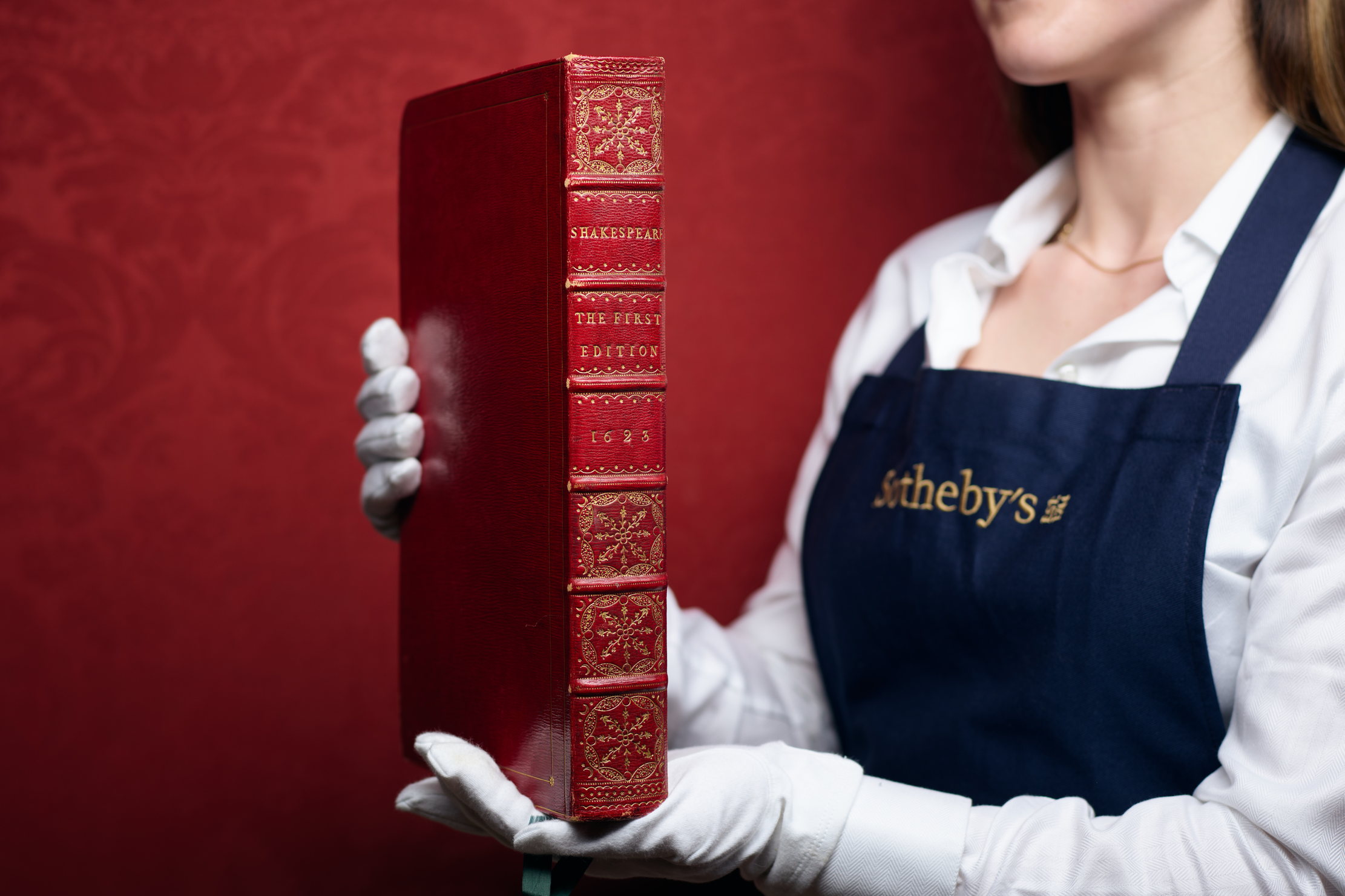

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby's

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby'sFour Folios will be auctioned in London on May 23, with an estimate of £3.5–£4.5 million for 'the most significant publication in the history of English literature'.

By Lotte Brundle