Clandon Park after the fire: The National Trust’s largest ever reconstruction project

Untangling the Gordian Knot.

It is more than two years since Clandon Park was consumed by fire. The blaze, which began on April 29, was caused by an electrical distribution board in the basement of the building and was reported to the emergency services at 4.09pm. Staff and volunteers evacuated the building, which was open to the public at the time, and, nine minutes later, the first fire engine arrived.

The fire spread rapidly, rising through the basement by way of a lift shaft that followed the line of an Edwardian predecessor. By 5.50pm, it had spread through every floor and the flames lit the evening sky (Fig 1). The following morning, the smouldering house was a roofless, gutted wreck. The fire services closed the incident on May 8.

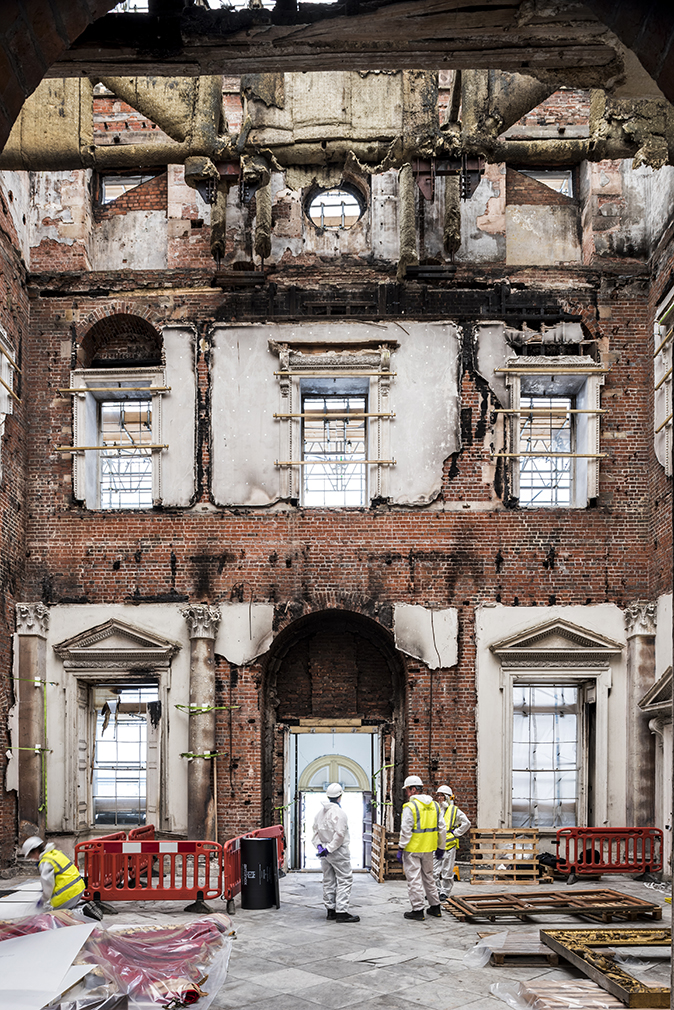

The dramatic spectacle of the burning country house, which had been rebuilt by Thomas Onslow in about 1730 (Fig 8), anticipated to the full its calamitous effects (Fig 3). As the fire report succinctly states: ‘Clandon Park was 95% damaged by fire, leading to the collapse of the roof and 95% of the internal floors.’ Despite this, some important architectural fittings have survived, including the principal fireplaces, and sorting through the debris has revealed fragments of decorative plasterwork from the interior (Fig 4).

No less devastating was the loss of its contents. Despite the crisis starting in mid afternoon, few furnishings were removed. In as far as any two emergencies can be compared, this is in striking contrast to incidents at Hampton Court in 1986, Uppark in 1989 and Windsor Castle in 1992. The contrast is, as yet, imperfectly explained. Public attention has been focused instead on the handful of objects that survived, some—such as the remains of Clandon’s state bed—almost miraculously, considering the state of the chamber it stood in (Fig 7). The architectural fragments, extant furnishings and works of art cleared from the ruins are now stored off-site awaiting conservation.

In the months after the fire, the technical difficulties of extracting steel inserted into the building in the 1960s, combined with safety concerns about melted lead from the roof, meant that the ruin remained open to the weather until the end of October 2015. Again, this seems slow, although, in fairness, changing safety standards have greatly complicated the process of securing a ruin on this scale. The scaffolding (Fig 2) will be in place for several years.

The fire has come at a fascinating moment in the Trust’s history, when there has been growing criticism of its attitude towards the properties in its care. To critics, it has become embarrassed and confused by these buildings and their contents, uncertain as to their popular appeal and even their significance. It has riposted by citing the scale of its financial commitment towards conservation and the many projects it has undertaken, most recently at Knole, Kent.

It is easy for critics to take potshots at a big institution, but, in this particular case, something has evidently gone wrong. The Trust’s curatorial branch has effectively been marginalised within the organisation. The expert panels it has long relied upon—of Arts, architecture, archaeology and gardens—have been wound up and their roles subsumed elsewhere. A recent internal review has implicitly acknowledged the problem and, in response, the body promised in October 2016 almost to double the number of curators, from 36 to 65, over the next two years, as well as to appoint a Director of Curation and Experience to lead them. In view of these changes, the treatment of Clandon becomes a bellweather for the Trust’s developing attitude to its houses.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Clandon was insured on the basis of like-for-like reconstruction, so, setting aside the option of demolition, it was almost inevitable that the building would be reconstructed in some way. However, Clandon was acquired by the Trust in 1956—it was not a direct gift from the Onslow family, but purchased as a bequest by Lady Iveagh from them—because it was a major 18th-century country house with important contents. Today, the qualities that imbued this property with significance have been almost entirely lost. As if to pre-empt the criticism that it is engaged in a vain project to replace the irreplaceable, the Trust has not plumped for a full rebuild, as it did for Uppark.

Instead, an ‘international design competition’ was launched on March 9 to identify ‘a world-class interdisciplinary design team’, led by an architect, that will bring Clandon ‘back to life through new uses’ (as yet unspecified). More particularly, the project director hopes for ‘the careful restoration of significant historic rooms with the reimagining of other spaces, on the upper floors’. There is much in these grand statements of intent that remains deliberately open to wide interpretation, but, in merely financial terms, this will be the largest project of its kind undertaken by the Trust.

Given the huge liabilities involved, it is almost inevitable that the shortlist will be led by large commercial firms of architects, who will aspire to create grand modern interiors in the upper floors. They will then co-opt the experience of much smaller firms of conservation practices, who will tackle the room restorations. Such an arrangement places the emphasis of the project on the new additions to the building; reading between the lines, it is hard not to suspect that the Trust is playing the games of many modern museums, plotting a prestige extension to a Georgian building in order to relate it to a contemporary audience. This begs the awkward question of to what purpose is this restoration really being undertaken?

On this point, the Trust apparently remains, as yet, undecided. The complexity and scale of the project present themselves like a Gordian knot and, rather than cut the tangle by assuming a clear philosophical approach, the organisation is trying to tease out the strands before committing itself. This seems sensible, but there are limits to what such an approach can achieve; at some point, the Trust as a patron needs to articulate clearly what it wants. Certainly, the vague aspiration that the house be brought to life seems inadequate in this regard. Not only would the alternative—putting it to death—be an absurdity, but even the modern additions won’t in themselves give the building a contemporary relevance unless undertaken with a clear sense of function.

There are hard decisions, too, in prospect even with regard to the restoration of the historic interiors. Take, for example, the superb Marble Hall, which survived up to the fire in broadly its 18th-century form (Fig 5). However, the hall also underwent an important 19th-century alteration. When the external porte-cochère was added to the building in the 1870s, the main external door to the room was partially filled in, losing a skylight. The outline of this doorway and its rough brick infilling are now clearly visible in the gutted interior. Probably at the same time, a shallow internal porch of timber was created inside the door to keep out drafts. The remains of this structure, which partially obscured the internal doorcase, are still visible.

When the interior is restored, should the 19th-century alterations be removed (and the porte-cochère shifted away as a garden pavilion) to take the room back to its condition at the time of its builder’s death in 1740 or do they have integrity as evidence of the development of the house? Powerful arguments can be marshalled on both sides and, at least, the issues are relatively clear cut. What happens with more nuanced discussions about changes to the plan and circulation arrangements made in the 18th and 19th centuries to the original design or with later decorative schemes? These considerations graduate almost seamlessly into the questions of how the rooms should be furnished and presented in the future.

The problem for the Trust will be that, in each case, the issue will need to be painstakingly discussed and agreed on some notionally objective assessment of ‘significance’. All this in an environment in which there will inevitably be someone who sees significance in practically everything. Ultimately, the Trust has to upset someone; the challenge will be to formulate a clear perspective that answers the offence, otherwise, it will simply end up annoying everyone. It is salutary to think of how different these problems would look if there was an owner whose tastes, delight and interest could arbitrate in such discussions (none of these words, of course, have a bearing on ‘significance’).

Another decision that is being left to the future is the whole arrangement of the setting. This is unfortunate, not least because the one authentic surviving element of the building is the exterior. Hopefully, the project will catalyse major changes to the present arrangements, all effectively inheritances from the way the property was taken into the Trust’s care 70 years ago with only a tiny amount of associated land. As a result, visitor facilities were crammed into the house, a modern road cut past the house to serve a garden centre and visitors approached not through the historic park, but from the rear of the building. For the future, and through negotiation, surely the house should be approached down the front drive through its Capability Brown park?

It would be unfair only to sketch out the problems presented by this ambitious undertaking. The restoration work to the house promises to be of enormous popular interest and the Trust is already prepared to harness this. The interior house was opened up just before Easter, with protected walkways offering access to some of the principal ground-floor rooms (Fig 6). This has already attracted large numbers of visitors. The restoration of the rooms will also provide invaluable experience for developing a new generation of skilled craftsmen. The actual process of the work will be a force for good and deserves to garner much attention.

However, the time will come when the contractors leave, the scaffolding is dismantled and Clandon begins life as a renovated building. When the reopening comes, the question will remorselessly return: to what purpose has the Trust restored this building? One answer will be supplied by the photographs published to celebrate the reopening. Will they illustrate the re-created Palladian interiors or the new conceived spaces in the house? Will they see the value of the house in terms of its history or its future? There is no right or wrong answer, because both should seem important, but the emphasis will be significant. Hopefully, too, the problem of the building’s setting will have been resolved as well. If so, visitors will once again be able to grasp the combination of landcape, architecture and art that made Clandon—and English country houses generally— such a magnificent and compelling creation.

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.

-

In all its glory: One of Britain’s most striking moth species could be making a comeback

In all its glory: One of Britain’s most striking moth species could be making a comebackThe Kentish glory moth has been absent from England and Wales for around 50 years.

By Jack Watkins

-

Could Gruber's Antiques from Paddington 2 be your new Notting Hill home?

Could Gruber's Antiques from Paddington 2 be your new Notting Hill home?It was the home of Mr Gruber and his antiques in the film, but in the real world, Alice's Antiques could be yours.

By James Fisher

-

The strangest museum in London? Dennis Severs’ House is art installation, theatre set and 18th century throwback

The strangest museum in London? Dennis Severs’ House is art installation, theatre set and 18th century throwbackTactfully revived, Dennis Severs’ House defies categorisation, finds Jeremy Musson.

By Jeremy Musson

-

The millionaire who created a real-life toy train set on a human scale

The millionaire who created a real-life toy train set on a human scaleThe astonishing assemblage of buildings, machinery and memorabilia at Fawley Hill, Buckinghamshire — the home of Lady McAlpine and the late Sir William McAlpine — is testimony to one man’s remarkable enthusiasm for the railways, as Marcus Binney discovers. Photographs by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

By Marcus Binney

-

The Castle of Mey: Inside the Queen Mother's beloved home in Scotland

The Castle of Mey: Inside the Queen Mother's beloved home in ScotlandA visit to Scotland in the first months of her widowhood encouraged The Queen Mother to buy and restore a castle. John Goodall describes the history of the building and the achievements of the trust that has managed it for the past 22 years.

By John Goodall

-

Britain’s great railway stations: Victorian eclecticism, modern genius and one that is a true work of art

Britain’s great railway stations: Victorian eclecticism, modern genius and one that is a true work of artSimon Jenkins lauds our most romantic and architecturally significant railway stations, some of the unsung triumphs of British conservation.

By Country Life

-

Sandycombe Lodge: The house that JMW Turner created, restored just as he designed it, now open to the public

Sandycombe Lodge: The house that JMW Turner created, restored just as he designed it, now open to the publicA breathtaking amount of work has gone into re-creating Sandycombe Lodge, the house that Joseph Turner designed and lived in for much of his life.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

What next for Clandon Park? Time to breathe life back into this great house

What next for Clandon Park? Time to breathe life back into this great houseSimon Jenkins, former chairman of the National Trust, considers the next steps for Clandon Park in Surrey, two years after the fire that reduced it to a ruin.

By Country Life

-

Kedleston Hall: A National Trust gem restored to its extraordinary former glory

Kedleston Hall: A National Trust gem restored to its extraordinary former gloryIt's 30 years since the National Trust raised the money to buy Kedleston Hall in Derbyshire. The work done since then is nothing short of staggering.

By Country Life

-

250 years of Bath’s Royal Crescent: From Druidic influences to big screen fame

250 years of Bath’s Royal Crescent: From Druidic influences to big screen fame2017 marks 250 years since the first foundation stone was laid.

By Agnes Stamp