Civic splendour: St Mary's Guildhall, Coventry

The guildhall built as a symbol of Coventry's 14th-century prosperity and self-government has recently undergone restoration.

On May 20, 1340, Edward III issued a royal licence authorising ‘the men of Coventry to have a guild merchant with a fraternity of brothers and sisters’. In this licence are to be traced the origins of the great medieval Guildhall that almost miraculously survives next to the great spire and ruins of the former parish church of St Michael’s in the heart of the city. The Guildhall has recently undergone a £6 million restoration project that highlights the interest of this building and its outstanding collections.

Brotherhoods that drew together individuals in a shared trade were a commonplace of late medieval urban life and Coventry’s ‘guild merchant’, dedicated to St Mary, was conventional in form. Its membership, the licence continues, could draw up governing statutes and elect a master or warden. Religious observance was always central to the lives of these incorporated bodies and the guild, therefore, was also given permission ‘to found chantries, [dispense] alms and [undertake] other works of piety’. Typically, a guild adopted a chapel in a convenient parish church, paying for priests to say divine service and financing improvements to them.

Almost immediately, St Mary’s Guild began to secure property to create a home for itself. In architectural terms, guildhalls resembled grand residences, typically comprising a great hall — for feasts and gatherings — a kitchen and services, as well as withdrawing chambers. A deed dated April 14, 1347, described a tenement, screened from the street by a row of five cottages and next to St Michael’s church (as well as the former site of Coventry Castle), as having ‘become the site of St Mary’s Hall’. The great hall was probably of timber frame and was raised above a surviving vaulted undercroft of stone.

St Mary’s Merchant Guild was the direct product of a power struggle in Coventry. The 14th-century wealth of the city was largely derived from the wool and cloth trade and its burgesses were increasingly impatient for a degree of self-determination. Standing in their way was the Benedictine priory of Coventry, which had long dominated the life of the city and exercised authority over a large section of it termed the Prior’s Half. The priory church was the joint cathedral of the Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield and, curiously, the only English cathedral destroyed at the Reformation.

In 1330, the determined figure of Queen Isabella, wife of Edward II, was granted the other part of the city, known as the Earl’s Half, and, by 1336, had entered into a protracted legal dispute with the prior over their relative rights. She enlisted the support of the city burgesses, for whom she secured valuable trading rights. The licence to found St Mary’s Guild, which stood in the Earl’s Half of the city, presumably had her tacit support and represented an attempt by the merchants to articulate their collective interests. Others in the Earl’s Half quickly followed suit: a Guild of St John the Baptist was founded in 1342, a Guild of St Katherine in 1343 and, a little later, the Guild of the Holy Trinity in 1364.

In the meantime, the Earl’s Half obtained various privileges, including the right to appoint a mayor and bailiffs. The first mayor, John Ward, was installed in St Mary’s Hall in 1349, evidence that the guild was inextricably associated with the developing institutions of civic government. Six years later, in 1355, Isabella, then Queen Mother, and the prior formally patched up their differences. Despite the devastation of the Black Death from 1348, Coventry now enjoyed a period of exceptional prosperity; in 1377, it was reckoned the fourth wealthiest city in the kingdom.

The burgesses of the town, partly through the medium of guilds, poured money into the expansion of their parish churches and particularly that which commanded the Earl’s Half of the city, St Michael’s. In the 1370s, two brothers, Adam and William Botoner, both former mayors, began work to the aggrandisement of the church with a gigantic tower. As work to its battlements — the famous spire is a slightly later addition — was completed, a new initiative to consolidate the power of the guilds was already in train.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

On June 30, 1392, Richard II issued a licence uniting all the guilds in the Earl’s Half of the city to form the ‘fraternity and guild of the Holy Trinity, St Mary the Virgin and St John the Baptist’. They were permitted to acquire additional property, too, to an annual value of nearly £100 in order to support nine chaplains and undertake other ‘works of piety’. This exceptionally wealthy guild effectively constituted the city’s governing body. As a consequence and to mutual advantage, it henceforth attracted a glittering circle of royal and noble figures into its membership.

It was almost certainly in response to this union of the guilds that the decision was taken to rebuild, with guild subvention, St Michael’s as one of the largest parish churches in the kingdom. It may be no coincidence either that the celebrated Mystery Plays of the city are first documented in 1392. More certainly, plans were immediately set in train to create a new guildhall on the site of St Mary’s Hall. According to the city annals, construction began in 1394 and was completed by 1414 (although work actually seems to have continued into the 1430s).

The timber-frame hall was cleared and its vaulted undercroft extended northwards by demolishing the line of cottages that had previously separated the old building from the street. This allowed for the creation of a splendid new hall gable immediately facing St Michael’s Church with a large three-part window externally framing a line of niches for sculpture. The composition evokes the backdrop to an altar in a church turned inside out and it’s unfortunate that there is no record of what the lost sculptures represented (Fig 3). Perhaps incongruously, the extension of the undercroft was leased out in the 15th century as a tavern.

Entrance to the Guildhall from the street is through a gatehouse built probably in the early 15th century, immediately to the left (east) of this gable. Its vaulted passage leads to a small internal courtyard with a stair — once roofed for shelter, but now fully enclosed — rising to the hall on one side of it. The visitor would originally have entered the hall via a so-called screen’s passage, a corridor created within the main volume of the room by an internal timber partition. Also opening onto this passage were three doors to the original services: the kitchen, buttery and pantry. The screen has long vanished, but a minstrel’s gallery now exists over the passage and, during the recent works, has been made accessible up a new spiral stair.

This splendid interior has in some important details been altered from its 14th-century appearance. The original encaustic tiled floor, for example, was replaced by boards for dancing in 1755 and most of the roof, apart from its carvings, was renewed by the city engineer, Granville Berry, after serious bomb damage in 1941 (a similar roof begun in 1391 has survived unscathed in Holy Trinity Church nearby). That said, it’s still possible to understand why this interior would have surprised and impressed a 14th-century visitor (Fig 2).

At this date, halls were usually covered by open roofs of high pitch. Often, too, they were divided internally by supporting posts or arcades and possessed tall side windows (often partially unglazed) incorporating window seats. Here, by contrast, the internal space is open, the roof low-pitched and its surfaces panelled. No less remarkably, the upper two-thirds of the walls dissolve into a grid of windows. The closest parallel for the whole composition is not another domestic hall, but the chancel of a church. In its original form, the interior of the great hall must have possessed a central hearth and a roof louvre to release smoke.

At the far end of the room is a dais for the high table hung with one of the treasures of the city, a tapestry that was woven in Tournai, Belgium, in 1505–15 specially for the guild. In the centre were images of Christ enthroned at the Last Judgement above the Assumption of the Virgin. To the left and right are male and female groups, the saints of Heaven above (with particular prominence given to the patrons of the guild) and a royal court below. The king and queen depicted are probably Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou, the former a member of the guild with close ties to the city and a posthumous reputation for sanctity that was promoted by Henry VII. The figure of Christ in Judgement was reworked after the Reformation as a figure of Justice. Both figures related to the use of the interior as a court.

The privileged space of the dais was lit to the side by a projecting oriel window and to the rear by the gable window overlooking the street. Within the window is a gallery of kings, a common iconography from the mid 14th century that proclaimed loyalty to the crown. Here the usual line of English kings is augmented by the figures of Constantine and King Arthur (Fig 1). The glass was almost certainly made in the workshop of Coventry glazier John Thornton, who contracted in 1405 to glaze the great east window of York Minster. This is only part of a huge display of early-15th-century figurative glass that once filled the entire room and of which many fragments remain. According to 17th-century antiquarian William Dugdale, the side windows depicted ‘divers eminent persons that were admitted of this fraternity’.

One family that received particular emphasis in the glass was the Beauchamps, Earls of Warwick. It is probably no coincidence that in some technical details — such as the tripartite form of the dais window — the architecture of the hall bears comparison to the ambitious works they were concurrently undertaking to the castle and collegiate church at nearby Warwick. It’s likely that the master mason they employed at this time, Robert Skillington, was the designer of this exceptionally ambitious building in Coventry.

During the Reformation, the guild was dissolved in 1547 and, in 1552, the hall passed to the City Corporation. Opening off the hall are four chambers that reflect the long use of the Guildhall in the administration of Coventry. The Draper’s Chamber opens off the dias and has been variously used as a council chamber and courtroom.

At the opposite end of the hall, the original services have been reconfigured to create what are known today as the Old Council Chamber (Fig 4) and Prince’s Chamber (Fig 6). Both rooms are furnished with architectural salvage from local historic buildings inserted after the civic functions of the Guildhall had been transferred to the neighbouring Council House, completed in 1920. The former also includes the Great Chair of about 1400, ornamented with the elephant and castle that was the emblem of the city, and the latter opens into the treasury, a vaulted chamber within ‘Caesar’s Tower’, which was partly rebuilt after bomb damage in 1940. Above these rooms is a spacious withdrawing chamber now known as the Armoury.

A stair from the hall also descends to the medieval kitchen, a space magnificently reconstituted in the recent works and, next to it, a vaulted muniment room of 1894. The kitchen interior gives a sense of the scale of the hospitality offered by the guild, which was enjoyed by monarchs (Fig 5), including Elizabeth I and James I. In 1861, it briefly served as a soup kitchen. Between the roasting fireplaces are narrow arches, possibly for storing fuel, a detail shared with the great kitchens of nearby Kenilworth Castle.

In 2022, a new working kitchen was extended from the building, allowing St Mary’s Guildhall to function today — after nearly 700 years as the seat of Coventry’s government — as a Cathedral Quarter tourist attraction and events venue, complete with a restaurant in the 1340s undercroft.

John Goodall is Country Life's Architectural Editor

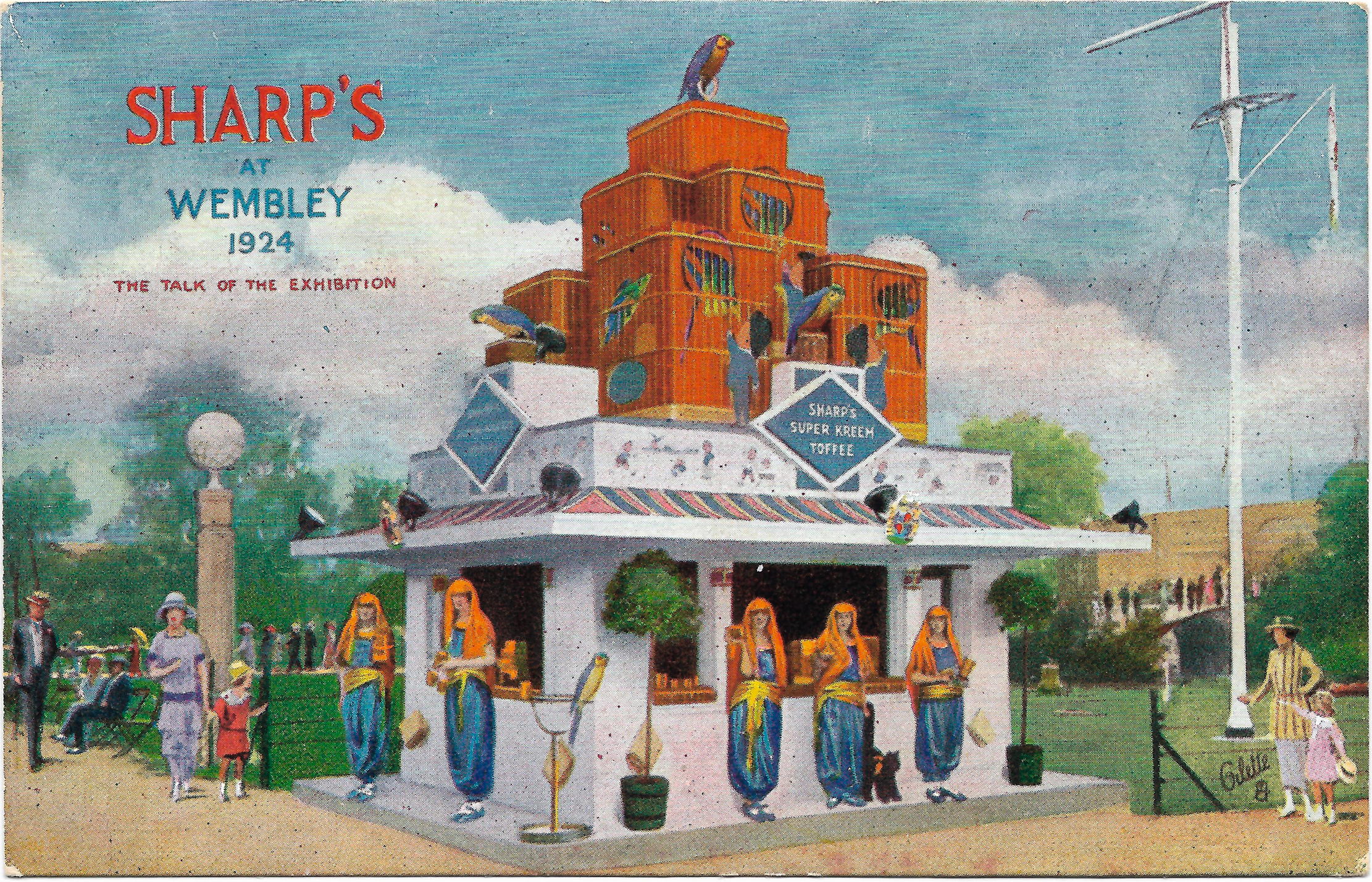

Wembley isn't just a stadium — it was a vision abd a pioneering adventure in the history of architecture

The 1924 Wembley Empire Exhibition was conceived on a vast scale, with a bewildering variety of displays that united such

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.