Chillingham Castle: 'Curiosity and beauty' at a spectacular castle that survived ruin by the skin of its teeth

Chillingham Castle, Northumberland — the home of Sir Humphry Wakefield Bt and the Hon Lady Wakefield — is a castle saved from the brink of ruin that is now a memorable home. John Goodall reports; photographs by Paul Highnam.

The coastal strip of Northumbria between Morpeth and Berwick-upon-Tweed enjoys a concentration and splendour of castles without European parallel. In the late Middle Ages, this was the so-called Middle March, a borderland between England and Scotland. Following the Union of the Crowns under James I and VI in 1603, some of these castles fell into magnificent ruin, such as Norham, Warkworth, and Dunstanburgh. Others have survived as living buildings. One such — by the skin of its teeth — is Chillingham Castle.

The remarkable story of its recent rescue from the brink by Sir Humphry and Lady Wakefield has previously been described by Jeremy Musson in Country Life (April 22, 2004). Against the odds, they have repaired the fabric and, with a shared interest in collecting and the Arts, turned Chillingham into a castle of curiosity and beauty, every room filled with eye-catching objects. Comparing the images of this article with those taken in 2004, it is possible to see how they have further consolidated their remarkable achievement over the past two decades.

[PODCAST: John Goodall on why Chillingham is one of his five favourite castles]

Chillingham is first documented in the 12th century as a possession of the powerful Vesci family, lords of Alnwick. There is no evidence that a castle existed here at this date, but there must have been a residence by September 1255, when Henry III paused at the site on his travels. His son, Edward I, also stayed there, in 1298. The property was subsequently mortgaged in the 1320s by its then owner, one Nicholas Huntercomb, to a certain Thomas of Heton, who quickly assumed control of it. In 1329, Thomas entailed Chillingham first on his eldest son — who died soon afterward — and then on an illegitimate son, another Thomas, a settlement that was twice contested, in 1345 and 1352.

It was in the context of this acrimonious family dispute, therefore, that on January 27, 1344, Thomas of Heton sought a licence from Edward III to ‘fortify and battlement his manor of Chevelyngham with stone and lime and to make the same a castle or fortalice to be held by him and his heirs without impediment’ (the original survives at Chillingham). Such licences were principally a passport to respectability, indicating that the recipient was of sufficient status to occupy a castle, the residence of a knight. In this case, however, it is tempting to speculate that other forces were at play. Was Thomas trying to manage his inheritance and use it to secure the succession of his illegitimate son?

In early 1344, English fortunes on the March hung in the balance. Edward III was focusing his attention on France and, between 1341 and the Battle of Neville’s Cross in 1346, David II of Scotland made repeated raids into England. Despite such upheavals, the presumption must be that the licence was connected with significant building works at Chillingham. In its present form, the castle is laid out on a four-square plan with a tower at each corner. From irregularities in the masonry, it is quite clear that its plan has evolved over time and the only structure that can be confidently dated on stylistic grounds — in this case, a small traceried window — to the 14th century is the southwest angle tower. There is no reason to think of Thomas as a vastly wealthy patron and this tower might simply have been added to the existing residential buildings to dignify and protect the property.

When Thomas died in 1353, it was a legitimate son, Alan, who actually took control of Chillingham. Thomas ‘the bastard’ died a decade later, but his younger son, Henry, determined to press his claim to the inheritance by force. In February 1387, it was reported to Richard II that Henry and a group of accomplices had entered the castle of Chillingham ‘by craft’ and imprisoned Alan in ‘a tower’ there. The King appointed an escheator to release Alan, but the royal officer was refused entry and, on May 25, the Earl of Northumberland and John Nevill of Raby, the two dominating figures of the March, were ordered to enforce the royal will. Alan died before his release, however, and Henry — evidently his legitimate successor — inherited Chillingham Castle.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In 1401, Henry died without male heirs and his property passed to his three daughters, who were six times married. Under their ownership, the castle was vaguely described in 1415 as being in the possession of Alan’s ‘heirs’ and, in 1426, as their collective property. By the 1440s, however, it had come into the hands of a much more powerful Marcher family, the Grays. They were longstanding owners of Heaton (or Heton) Castle and presumably, therefore, somehow kinsmen of the Hetons. A direct link between the two families is further implied by their use of a common coat of arms — a lion rampant in an engrailed border — its background tinctured respectively in green or red. Such differencing of arms was often used to celebrate affinity or acknowledge an important inheritance. It also speaks of the significance of this acquisition to the Grays that Chillingham — rather than Wark Castle, which was acquired by them in 1398, or Heaton — became their seat.

The first evidence of this change of ownership is the astonishing monument to Sir Ralph Grey (d.1443) and his wife, Elizabeth, in Chillingham’s tiny parish church (Country Life, April 10, 2013). This is one of the finest 15th-century funeral monuments in England, encircled by images of northern saints, and the contrast with its architectural setting makes clear the stature of the Greys. It is also surely an assertion of ownership. This impression is reinforced by the superfluity of heraldry and family badges that it displays. These include the repeated emblem of a five-rung ladder, a punning reference to gre, meaning ‘a stair’ in Middle English and Old French. It also recalls a history of the Scottish wars written by Ralph’s great grandfather, Thomas Grey, called the Scalachronicon or ‘stairway chronicle’ that opens with a vision of the ladder of history, the final and fifth rung launching to the future.

Sir Ralph, whose remarkable military career was explored by Gilbert Bogner in Archaeologia Aeliana (2013), died in France and this monument was probably commissioned by his namesake son. Sir Ralph the Younger was a prominent Lancastrian in the Wars of the Roses and played an important role in the final attempt in 1464 by Henry VI and his Queen, Margaret of Anjou, to topple Edward IV. He refused to yield Bamburgh to an overwhelming Yorkist force. During the ensuing bombardment, he was wounded and the castle was surrendered. Sir Ralph’s defiance cost him his life.

During the 16th century, Chillingham is occasionally mentioned in records and wider events. A survey of 1509, for example, estimated that it was capable of accommodating a considerable force of 100 fighting men. In this period, a gated and walled enclosure around the castle — fragments of which still survive — must have greatly enlarged its area. Then, in 1537, during the popular rebellion known as the Pilgrimage of Grace, it was held against the rebels and possibly damaged. The next important round of changes, however, followed another dynastic twist that united the possessions of two branches of the Grey family in the ownership of yet another Sir Ralph. He emerged in 1590 as perhaps the greatest landowner in Northumberland, with an estimated estate of more than 250,000 acres.

Sir Ralph was wealthy and belligerent, quarrelling with all his neighbours and even attempting a duel in the churchyard of Berwick-upon-Tweed. The authorities also suspected him of being a Catholic. He did, however, have a remote relative through whom he helped Lord Burghley and his son, William Cecil, communicate with James VI of Scotland. Consequently, when the King acceded to the English throne in 1603, rewards flowed thick and fast. In particular, he played an important role in the settlement of land ownership in the debated lands between the two kingdoms. His local authority was naturally extended by the long-term imprisonment of Henry Percy, 9th Earl of Northumberland, following the Gunpowder Plot in 1605.

Across his owned and leased estates, Sir Ralph abandoned and even stripped many castles, but he modernised Chillingham. Under his direction, almost certainly between 1603 and his death in 1623, the — probably — rambling medieval buildings were augmented to create the regular, four-square building we see today. As part of this work, he rebuilt the north range as the entrance front (Fig 3) and also the southern range, detailing both externally with sculpture and heraldry. In the process, he created the present, dramatic approach to the building. This takes the visitor up a flight of stairs and through a central gateway (Fig 4) to a small internal courtyard. Straight ahead is a loggia and a second flight of stairs to the main door of the house (Fig 1), populated by six sculptures of the Nine Worthies. He also transformed the interior of the building, with decorative plasterwork (Fig 2) and large-scale fireplaces (Fig 6).

Meanwhile, Sir Ralph’s son, also Ralph, was already politically active. He was created a baronet in 1619, sat as an MP in 1621 and was made Baron Grey of Warke in 1624, a reference to the family’s other major castle. On the outbreak of Civil War, he sided with Parliament and briefly became commander in chief of its eastern forces in 1643 before serving as Speaker of the House of Lords. Correspondence with his steward reveals the damage done to his Northumberland estate during his absence with Scottish troops pillaging the locality. In a letter dated January 20, 1646, Sir Ralph was informed: ‘Your Honour’s deer and wild cattle, I fear will all die, do what we can.’ This note is the earliest unambiguous reference to the celebrated herd of wild Chillingham Cattle that remains a major attraction.

Following the Restoration, the 1st Baron successfully sought for pardon from the King. When he died in 1675, he was succeeded by two sons. The younger of these, Ford, 3rd Baron, had a tumultuous political career in which he conspired with the Duke of Monmouth against James II and was elevated to the peerage as Earl of Tankerville — the title referring back to a 15th-century French possession of the family — by William III. He also built Uppark in Sussex. Following his death in 1701, the earldom was revived in favour of his daughter, Mary, and her husband, Charles Bennet, 2nd Baron Ossulston. It then descended with the castle into the 20th century.

A survey of Chillingham Castle in 1711 by Henry Pratt, as well as an engraved view of 1726 by the brothers Samuel and Nathaniel Buck, suggests it remained in good repair. The former shows a formal garden laid out to the south of the building, probably a creation of the improvements early the previous century. This has now been restored, together with later parterres to the west (Fig 7). Further repairs to the castle were undertaken in 1753 (according to the dates on lead hoppers) and, in 1803, the east range was reordered by the Edinburgh architect John Paterson. He was trying to improve an impossible interior for fashionable living.

By this point, Chillingham was attracting a steadily growing stream of tourists. They did not come in search of a fashionable building, but a historical curiosity. There was perennial interest in one object first described in 1675 as ‘a chimneypiece with a hollow in the middle of it; wherein (’tis said) there was found a live Toad, at the sawing of the stone.’

Even by the 1750s, the stone itself had vanished from the hall (Fig 5), but a board with a verse and image remained to entertain visitors. Chillingham’s burgeoning celebrity was further enhanced by the writings of Sir Walter Scott and, in 1824, the 5th Earl commissioned Sir Jeffry Wyatville, the architect of George IV’s remodelling of Windsor, greatly to enlarge the building. In the event, only modest changes were actually undertaken. Edward Blore designed the magnificent gates to the castle in 1835.

Following the death of the 7th Earl of Tankerville in 1931, the castle was offered for lease. There was no interest, however, and its ‘Antique and Modern Furnishings, Pictures, Silver, Old China, Books & Old Tapestries’ were auctioned off between April 11 and 14, 1932. After a fire in the empty property, Sir Albert Richardson helped restore the north range — hence a lead hopper there dated 1942 — but, in the middle decades of the century, the castle began to fall into ruin.

It was offered to the National Trust, but it was not until the 10th Lord Tankerville, then resident in the US, was persuaded to sell it to the Wakefields, who themselves claim Grey ancestry, that its fortunes changed. Thanks to their heroic and ongoing labours, a visit to Chillingham Castle is not quickly forgotten.

Visit www.chillingham-castle.com to find out more and plan a visit.

Chillingham Castle: The owner writes

Following John Goodall's article first appearing in Country Life on February 7, 2024, Sir Humphry very kindly wrote a letter to add further clarification on several points, a letter which we're delighted to repeat here:

Further to your excellent article on Chillingham Castle, may I say:

- You write about Chillingham’s 13th century de Heton owners. They were Greys from their nearby Heton Castle (now usually referred to as Heaton Castle — Ed.) which was only sold by my mother-in-law for Death Duties in the 1960s. My wife, my own 4th-cousin, keeps the Grey line here after all those centuries which makes our famous ghosts happy.

- You write that the family applied for our 1344 ‘License to Crenelate’. No, it was ‘Awarded’ by Edward III and hails from the Wakefield Tower, in the Tower of London complex where, just then, my direct forbear was ‘King’s Clerk’.

- You rightly describe Sir Ralph Grey’s 1400s’ tomb as the ‘finest in England’. But it was planned for Westminster Abbey: Sir Ralph was a national hero for keeping 150,000 (sic) Scots at bay. His son, another Sir Ralph, had the tomb built, but then conquered Alnwick and Bamburgh Castles, declaring ‘Independence for the Northeast!'. Sir Ralph Junior’s head was soon gracing Newcastle Gates, the tomb sent home in disgrace.

- You write that I persuaded the Lord Tankerville (a 15thcentury Grey title) to sell me Chillingham. No, I bought a few hundred acres and was given the Castle ruin. Because the Castle had never been sold and for my having a Grey blood wife.

Very sincerely,

Sir Humphry Wakefield

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.

-

Gill Meller's recipe for a seasonal new potato omelette, with smoked garlic, onions and Cheddar cheese

Gill Meller's recipe for a seasonal new potato omelette, with smoked garlic, onions and Cheddar cheeseBy Gill Meller Published

-

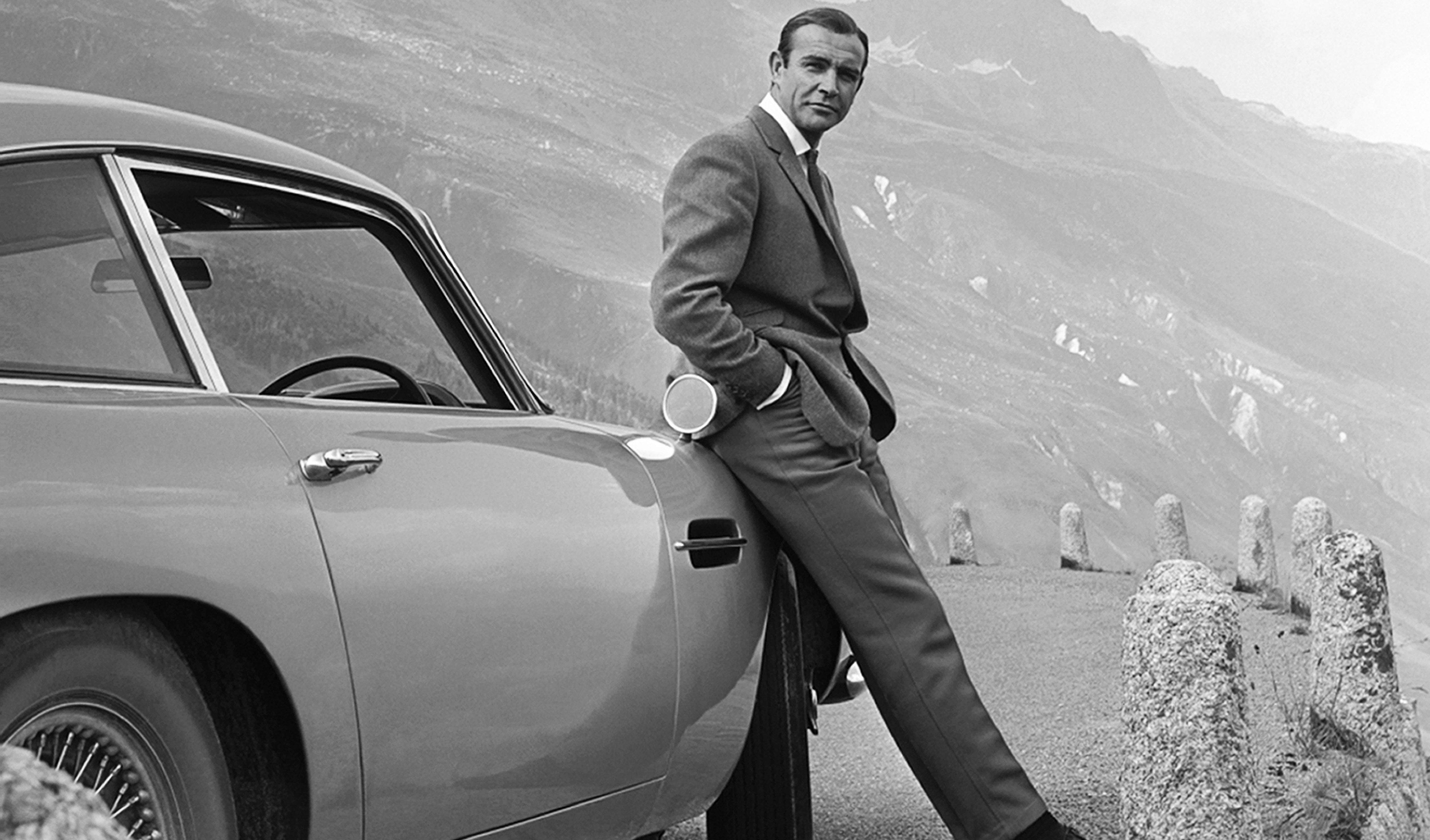

Bond's Aston Martin and Welsh rarebit: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 10, 2025

Bond's Aston Martin and Welsh rarebit: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 10, 2025Thursday's quiz celebrates pedestrian crossings and tests your language skills.

By Toby Keel Published