Chequers: The salvation and restoration of a house which became the Prime Minister's official country retreat

Chequers Court, Buckinghamshire, is the country seat of Britain’s Prime Ministers. By courtesy of the Chequers Trust, John Goodall paid a visit to find out more, and uses a diary to explain the circumstances of its magnificent Edwardian transformation. Photographs by Paul Highnam.

Chequers Court is popularly familiar as the country seat of the Prime Ministers of Britain. It is not, however, a public or Government-owned building — rather, it is managed by a trust set up for the purpose by Ruth and Arthur Lee, later Viscount Lee of Fareham, in 1917.

The couple first leased — and later bought — this Elizabethan house as a second home in 1909 and restored it with the help of the doyen of Edwardian architects, Sir Reginald Blomfield. When the Lees first undertook the transformation of the house in their late thirties, they had no idea of where it would lead them.

To rediscover how the Edwardian renovation of Chequers Court unravelled, it is necessary to turn to Ruth’s unpublished diaries. These are preserved in the house and run in a continuous sequence from 1906 to 1946. Each volume is bound in red leather and locked by a single clasp. Within them is to be found an unusually detailed account of how the Lees fell in love with Chequers and then went about its restoration.

As we shall discover in another piece to be published on the Country Life website on May 31, they also reveal how the decision to gift it to the nation was catalysed by a plane crash in 1912 and then came to an unexpectedly rapid fruition on New Year’s Day, 1921.

Ruth Lee, née Moore, was from New York, the daughter of a rich banker, who met her future husband when he was posted to America as a military attaché. He was the son of a Dorset rector and had joined the Royal Artillery in 1888. They were hastily married when it seemed that Arthur might be sent to the South Africa War, but, in the event, he left the army the following year to enter into politics and won the Conservative candidacy for Fareham.

They both had strong interests in the Arts and politics. With Ruth’s money, they mixed in a wealthy and influential circle. In 1902, they purchased their first motorcar, which allowed them to live between Westminster and their leased constituency home, Rookesbury. To judge from the diaries, they also lived very closely together.

The Lees’ connection with Chequers began early in 1909, when they determined to take a house in the Chilterns so as to be close to their friends, the Maxes. On January 10, Ruth’s diary notes: ‘We think it would be so delightful if they [the Maxes], the Olivars and ourselves could be all permanently settled in that neighbourhood.’ Over the next few days, they visited several houses in the area, including Chequers on January 31. From the first, it made a strong impression:

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

‘I think I like it better than any house I know, but inside it is in very bad repair and hideously inconvenient. It wd cost so much to put right that we feel it is out of the question for us.’

Chequers is a rambling and many-gabled Elizabethan manor house. The initials of its first builder, the courtier William Hawtrey, and the date 1565 are cut on one of its north gables. As the Lees first saw it in 1909, it incorporated a central courtyard and its brick walls had been stripped of Regency stucco less than 20 years previously in 1892. This cleaning work, part of a wider restoration of the property, was done at the suggestion of Sir Reginald Blomfield, who had been invited by the then owner, Bertram Astley, to advise on the gardens.

Nevertheless, for all its faults, in the final choice between Chequers and Watlington in Oxfordshire, the former clearly won out. ‘It is so beautiful,’ she wrote on February 2, ‘Wallington is like being married to a nice comfortable woman and Chequers Court like being carried off yr feet by Helen of Troy.’ The negotiations for the house were complicated because the Lees did not have the £130,000 to buy the estate outright.

Nor were they happy with a straightforward lease from the Astley family trustees, who owned the property, perhaps because they still hoped to have children.

The protracted discussions at home and between lawyers were dubbed in the diary ‘playing at chequers’ and they came to a happy conclusion when a two-life lease of the partly furnished house was exchanged on April 28, 1909.

When the game was still in full flow, the couple began to buy architectural books and they had chosen their architect by February 16, when Ruth ‘telephoned Mr Blomfield who came to see us and we had long consultations about “Chequers”’. It is unlikely that his previous involvement here in 1892 recommended him. Rather, he was a solid choice, well published and accomplished in the field of ‘Renaissance’ architecture.

Blomfield’s report on the house arrived 10 days later:

‘It is very satisfactory on the whole and he has made some most excellent plans for alterations… He purposes a good south dining room and moving the kitchen and larders away from the South side so will get the benefit of the terrace.’

The Lees, meanwhile, determined that the interiors should be furnished with historic or reproduction furniture and panelling. Accordingly, they visited antique shops, auction houses and even factories to find what they wanted. On June 18, at High Wycombe, they found, for example, Nicholls and Janes:

‘A real find… where they make the very highest grade of antique furniture!… Such a nice man Mr Jane[s]. We bought several of his “models” genuine old pieces and a few copies of chairs. We expect to have him do a good deal of work for us.’

Gill and Reigate in London became their main supplier of old furniture and panelling and Ruth plotted the possible positions of rugs using paper cutouts scaled to the size of Blomfield’s plans.

Over the same period, the Lees were also visiting Tudor houses, such as Sutton Place, Loseley and Bramshill, as well as at least one modern house in the Tudor style, Huntercombe near Henley. Detailed impressions of each were recorded in the diaries.

They additionally began scouring museums for inspiration. On June 13, for example, they went ‘to S. Kensington Museum to look at plaster ceilings for Chequers’. The galleries were not yet open and Arthur gained admission by showing his card to a policeman. The following month, they visited again with Blomfield:

‘Sir Cecil Smith [the director] himself showed us about and we found one [ceiling] from Broughton Castle for the drawing room and another that might be adapted for the hall.’

By the end of July, everything was ready and more than 200 men were ready ‘to pounce on Chequers’. There was a brief delay when it turned out that ‘young Astley’, who, as owner, needed to approve all the proposed changes, ‘has gone off and left no address!’. Work began, however, on July 23, when all the furniture in the house was marked up and inventoried.

During the inventory process, the solicitors involved discovered the death mask of Oliver Cromwell, one of several heirlooms of the house associated with the Lord Protector, locked up in a cupboard.

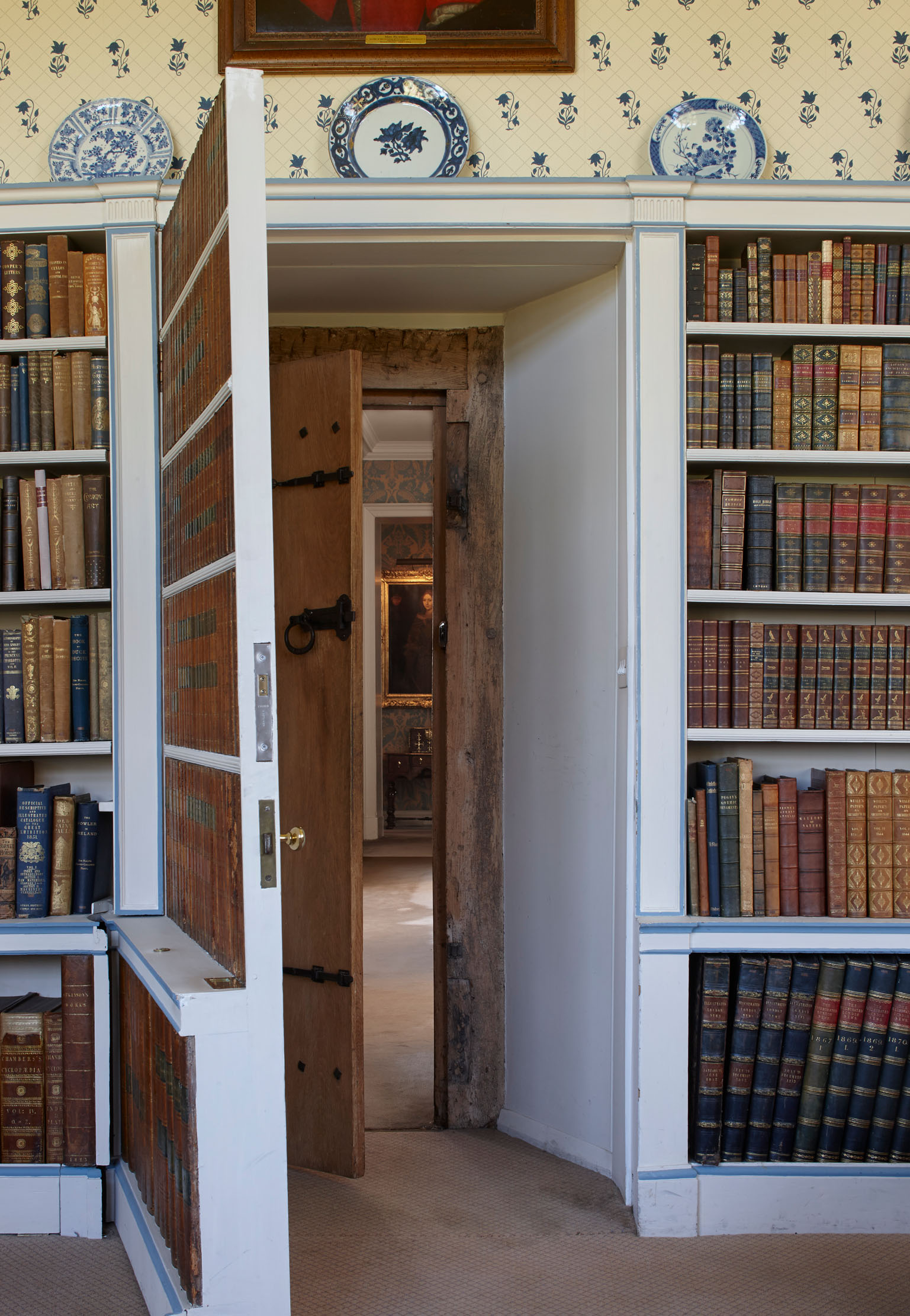

Next, the building work began. Three days later, the house looked to Ruth ‘like pictures of the San Fransisco [sic] earthquake and I can’t help feeling depressed about it’. Then, on July 28, she confided: ‘I can’t bear to think of things being pulled down at Chequers… It makes me feel an awful vandal.’ However, her customary optimism returned as the work brought to light hidden doors and features from the original house.

The Lees’ research into the history of the house redoubled in intensity. August 6, for example, was:

‘Another deliciously hot day… I read a history of the Hawley family out under the apple tree and A. and I talked about that and the Chequers pedigrees and continued to try to puzzle out in our minds the old… arrangements of the house’.

By October, the effects of Blomfield’s changes could be judged and the Lees turned their attention to the furnishings in earnest. There were repairs to historic fittings, including the heraldic stained glass, which was restored by an expert at the recommendation of the College of Arms. Practical matters such as heating, bathrooms, electricity, fabrics and paint colours also began to be discussed in the diary.

The Lees were involved in everything, consulting and overseeing all that was done. One particular bone of contention between them was the decoration of the central hall that was created by Blomfield on the site of a former courtyard, which began to take shape with its screen and upper gallery connecting the bedrooms in December.

Although the house remained uninhabitable, the Lees ate ‘dinner very grandly in the dining room with Champagne’ for Ruth’s 36th birthday on December 27. This debut meal was followed a month later by an entertainment for the whole workforce:

‘About 200 of them in the great hall at 7.30. Our first party. Done by caterers from Aylesbury. Hall quite full of long narrow tables prettily decorated with plants… A. spoke and told them history of Chequers… and healths drunk all round. Music and smoking after. All great fun.’

Four days later, on February 1, 1910, the diary states:

‘We’ve actually moved into Chequers… A. and I, Miss Mortlock and the scullery maid, Mary and one footman… Spittles and an “odd” woman make up our establishment — not of course counting the 150 workmen more or less who still remain — and likely to for a long time yet… the house looks very discouraging.’

There were more pressing money worries to face, too. The bill had doubled during the course of work and there were jitters on the American financial market, the foundation of Ruth’s wealth.

The financial crisis passed and still the work went on with at least one false completion. At the end of April, Ruth observed ‘woods full of primroses, violets and a few late anemones — but the house still full of workmen!’.

It was, in fact, late May before the house made its debut as a place of reception. Mr and Mrs Theodore Roosevelt came to stay during their visit to Britain; the former President, a great friend of Arthur, planted a cedar in the lawn on May 29.

Thereafter, there was a steady flow of glittering visitors through the sumptuous new interiors, including the Great Parlour. One of those attending on July 9 was Capt Scott, who ‘promised to think of Chequers at the South Pole’.

Then, on August 20:

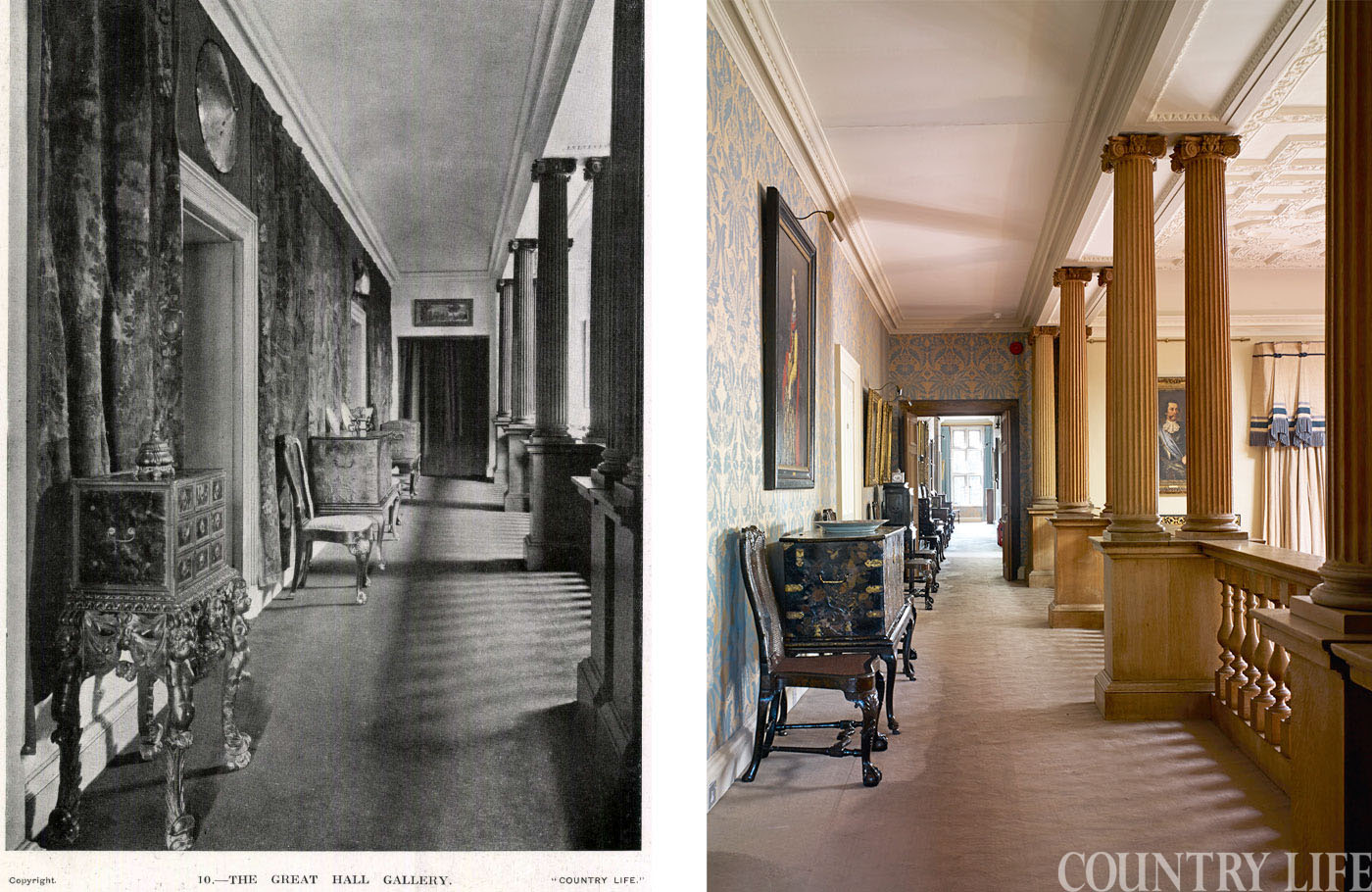

‘The editor [founding owner] of Country Life Mr Hudson also came and went very, very thoroughly over everything. He knew the house before and thought it totally uninteresting, now he says it will make a very interesting series of pictures and he seemed to approve of what we have done, was enthusiastic over much of it.’

On October 4 — ‘sunny and warm’ — Country Life’s brilliant but temperamental photographer Charles Latham came to the house:

‘I spent practically the whole morn. and all the early part of the afternoon following him around like a dog! I was able to help a good deal in arranging furniture and a little in making suggestions. I find that rooms cannot be photographed to advantage furnished as they are.’

Latham was still there the following day and stayed to lunch having ‘done the house very thoroughly’.

The article appeared on December 31, 1910, and both Arthur and Ruth were thrilled:

‘We are both delighted with it. We think it looks even more fascinating than the average and are quite thrilled to think we live in it and what we have done.’

How Chequers has changed — and stayed the same — in a century, as pictured in Country Life

We take a look at Chequers is now, and as it was 103 years ago, when Country Life visited following

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.