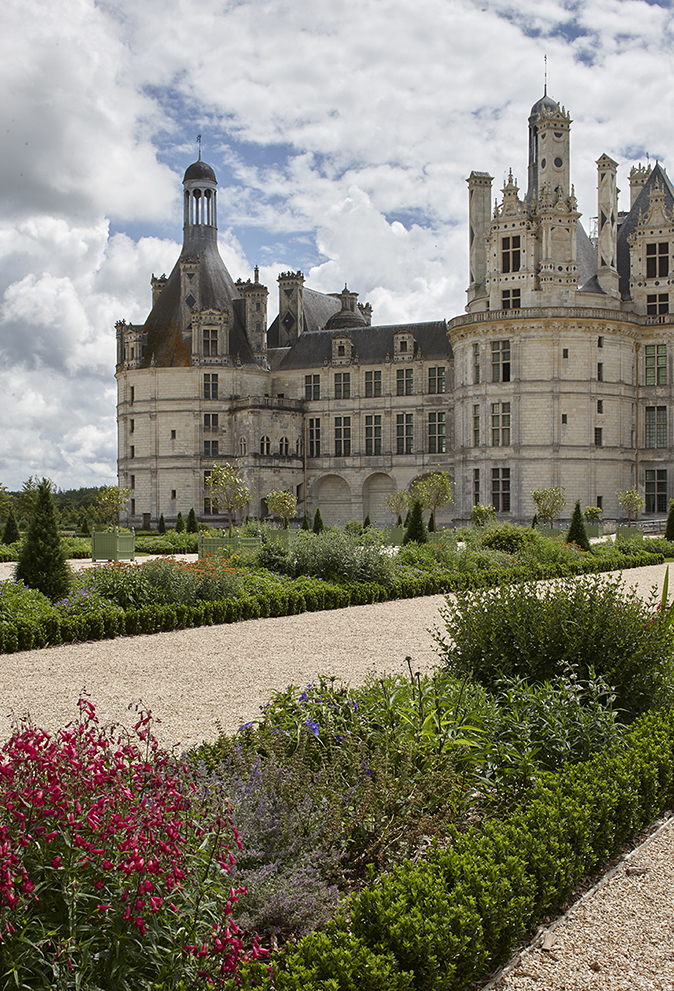

Château de Chambord: A jewel and its setting

An ambitious garden re-creation complements the architecture of perhaps the most celebrated château on the Loire and has linked it with its wider parkland. Tim Richardson reports.

Francois I’s gargantuan hunting lodge, the Château de Chambord, commenced in 1519, was conceived in the visionary sprit of the castles depicted in the celebrated pages of the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, miraculously rising up out of water in the middle of the forest, its gilded white towers and turrets gleaming in the sunlight.

At its centre is a richly carved, open-work staircase that rises up through three storeys at the core of the château. Consisting of two separate flights that never meet, the stair breaks through the roof of the central block – described as a keep or ‘donjon’ – as it soars up to dominate the roofline, a kind of skeletal dome adorned by flying buttresses.

For all the attention it receives in architectural studies, Chambord never appears in garden histories and received opinion is that that ‘it has no garden’. This was certainly true for the first two centuries of its existence, when it sat on a half-completed island, as well as for the past half century, when the terraces to the north and east of the château have been kept as simple grass plats, tabula rasae to the extraordinary architecture on view.

However, Chambord did have a garden – at least for a little while – and a new restoration, based on a parterre design realised in the early 18th century, is a convincing reassertion of the desirability of a garden at the site.

Completed in March 2017 after only seven months’ work, the restoration re-establishes a magnificent setting for this remarkable building and also effectively rebalances the estate, with château, gardens, river and surrounding forest now held in felicitous equilibrium. The budget for the restoration was €3.5 million, made possible through the generosity of the American financier and philanthropist Stephen Schwarzman. Associated projects include a grande promenade of walkways and rides through the surrounding forest, where deer and boar abound, a convenient boutique hotel on site and a winery (under construction).

Almost all the great Loire châteaux of the late 15th and 16th centuries boasted parterre gardens, several of the grandest with fountains, water tricks and central pavilions. The principal source for them is Jacques Androuet Du Cerceau’s mid-16th-century engravings. Little trace of these gardens survives today, however. At Blois, for example, they have largely been built over. At Chenonceau, the biggest of two 16th-century parterres was imaginatively remade in the 1920s by Achille Duchêne (who also designed the parterres at Blenheim). Modern visitors curious about gardens might visit Villandry, where a fantastical version of a potager was created from 1906, or Chaumont, which holds an annual contemporary conceptual gardens festival.

Now, Chambord can move to the the top of the garden visitor’s agenda. The restoration was not, however, based on a 16th-century design, for the simple reason that there was no garden there at that time, unless one counts a rectangular walled space shown at the north-west angle of the château in a plan of 1681. It is thought that this may have been a remnant of a productive garden linked to the old château of the Comtes de Blois. (There is also evidence of medieval stew ponds – now small lakes – in the surrounding woodland.)

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

A garden does appear on a Francois I’s original list of proposed appurtenances for Chambord and three gardeners are listed as employed in 1522, but it seems that nothing substantially ornamental was completed then or for several centuries.

The garden restoration is based instead on a much later tripartite parterre design whose construction is recorded in 1734, during the reign of Louis XV, and which was fully embellished and planted by the late 1740s. Before that date, an ornamental garden was apparently found to be untenable on the site, given that the grassy areas to the north, west and east of the château were more or less a marshland, criss-crossed by watercourses linked to the main River Cosson, which flows across the estate.

In Nicolas Perelle’s engraving of the château in Louis XIV’s time and in Pierre-Denis Martin’s painting of a hunting party of 1722–24, the château looks almost as if it is set on an island, with an insalubrious bog around the main entrance on the northern façade.

In fact, Chambord was more or less abandoned by the French monarchy after Francois I’s death. It was only during Louis XIV’s reign that it was ‘rediscovered’, when finance minister Colbert related that it was ‘in a pitiful state, without doors, without windows, without glass… it rained everywhere’. Nevertheless, the king enjoyed hunting there and made nine visits between 1668 and 1685.

In 1681, he engaged Jules Hardouin-Mansart to restore the building and to create earthworks with stone retaining walls. This helped to consolidate new terraces on the northern and eastern sides of the château, both to provide a firm foundation for a garden and to prevent flooding. The marshland surrounding the château was partially drained and the river itself diverted, so that it hugged the straight edges of the new terrace.

Hardouin-Mansart also submitted two parterre-garden plans to the king. It is believed that the second of these was begun, but, from 1684, he was engaged on the overhaul of the royal gardens at Versailles and, in 1686, all works at Chambord abruptly ceased.

The idea of a garden at Chambord would be revived again only after 1730, when the estate was in the hands of King Stanislas of Poland, Louis XV’s father-in-law. He successfully appealed to the office of the Bâtiments du Roi on the grounds of the prevalence of malaria around the château and, as a result, earthworks were reinforced, stone bridges were constructed to replace mud causeways and the river was dredged and widened around the château, before shooting off as a dead-straight canal to the south-east.

Finally, in 1734, a parterre garden was created to a new design, to be maintained by one Jean-Baptiste Pattard. According to a 1742 inventory, ‘the garden was then planted and the château, which had previously been sited in a swamp, was thereby made all the more impressive’.

Chambord subsequently passed to the Marshal-General de Saxe in 1745 as a reward for his victories over the British. This period saw the further ornamentation of the garden, particularly with regard to trees – double rows and a grid of chestnuts – and hedges of box and hornbeam. In addition, several hundred citrus trees in pots were introduced to the parterre; unusually, pineapples are listed as one of the main components of these pots.

A 1748 engraving by Jacques Rigaud is the best visual record of this period of the garden’s existence and has been a touchstone for the restoration. It depicts cut-turf fleurs-de-lys and double rows of young trees in the northern parterre. An estate plan dated 1756 corroborates this layout, as well as those of the eastern and north-eastern parterres. Archaeology has revealed that the positions of trees were mapped precisely on surveys, which has allowed for a remarkably accurate restoration in terms of tree placement.

The new gardens of the 1740s only lasted for 50 years. After the French Revolution, the château went into sharp decline. A condition report of 1817 stated that the moat had dried up and that the parterres, trees and hedges were overgrown and untrimmed. By the late 20th century, all that remained were some overgrown topiaries and horse chestnuts. In 1970, even these were taken away so that only plain lawns remained.

The centrepiece of the garden is its northern parterre immediately beneath the château. Two great rectangular grass plats adorned with fleurs-de-lys in gazon coupe (cut-turf figures) are flanked by double avenues of lime trees – a substitute for horse chestnut, currently blighted by disease.

Given projected visitor numbers – up to two million per year – it has been necessary to lay gravel rather than sand, which slightly reduces the garden’s delicacy close to. Narrow flowerbeds, termed plates-bandes, punctuated by yew cones surround the grass plats and also flank the wide central pathway. This begins a great northern axis that runs northwards across the canalised river and a semicircle of pasture into the forest beyond. Citrus in tubs are ranged about the garden in the summer months.

The north-eastern parterre, set at a diagonal, has been restored as a strictly geometric grid of 414 trees in four quarters, divided from the north parterre by a hornbeam hedge. The original trees used for the grid were horse chestnuts; the choice of native cherry (Prunus avium) as a replacement is not historically appropriate, but the spring blossom will undoubtedly be a crowd-pleaser.

At ground level, the simplicity of the parterre gardens creates a pleasing contrast with the fantastical roofscape of the château and the shapes of the yew topiaries seem playfully to echo the shapes of its towers and turrets. The château’s spacious roof terrace offers an unusual experience for the visitor.

Conventionally, at piano-nobile level, the view of a garden is almost static, framed by windows. From the roof of Chambord, however, the elevated visitor has the dynamic sensation of roaming through it from above. The pleasing variety of shapes, shadows and greens of the parterres and surrounding forest can also be appreciated.

The eastern parterre is not visible from the terraces open to the public and has a rather different character. It is formed of two rectangular plats of grass with plates-bandes and yew cones, as is the north parterre, but there are no cut-turf figures. The plantings do not observe the restrained tone of early-18th-century planting (which is pursued at Hampton Court’s restored Privy Garden, for example), however. Here are roses, cosmos, alliums, echinaceae, eryngium, gaura, giant fennel, cardoons and sanguisorba, with thyme used in place of box for the hedges, giving the effect of soft cushioning as opposed to crisp edging. (Elsewhere, the box hedging is being replaced with euonymus, because of box blight.) Crab-apples are being grown on supports at intervals along the flowerbeds.

The restoration team is clear that historical accuracy has been sacrificed here in the name of environmental sustainability, in that insect-friendly perennial plants have been used in place of annual flowers. The apples have been included as a nod to the fact that this parterre was converted into a kitchen garden at the end of the 18th century. In the northern parterre, the plate-bande plantings are not yet fully in place, but the plan is to follow a modern herbaceous rationale in that area, as well. This will certainly prove popular with visitors and it will not detract from the principal effect of the garden viewed from the château.

One other garden area has been restored at Chambord: an ‘English Garden’, which occupies a long and fairly narrow space along the western side of the château. Based on a garden plan executed in the 1880s when the site was in the hands of the Princes of Bourbon-Parma (the last of the Bourbons), it consists of meandering paths through lawns punctuated by large shrubbery beds. Its purpose now is to partially screen the château from visitors as they progress from the ticketing area and, in this regard, it is successful.

In a garden-history context, the 18th-century garden at Chambord was neither original nor a masterpiece, but that is not the point. Instead, it fulfils a humbler, subordinate role, sometimes befitting a garden, in that it offsets and complements a truly remarkable architectural set-piece. The garden restoration completes Chambord.

Château de Chambord, 41250, Chambord, Loir-et-Cher, France (00 33 2 5450 4000; www.chambord.org/en)

Credit: INTERFOTO / Alamy Stock Photo

'Permission to marry your daughter, sir?' – Why you still need to ask for her father's blessing to get married

Asking the father's permission to marry his daughter is hopelessly outdated yet remains an absolute essential part of the rituals

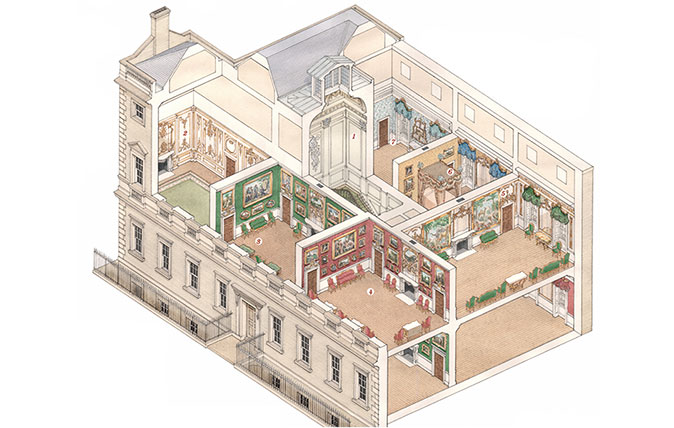

Credit: Country Life/Stephen Conlin

Norfolk House: The lost London palace that was razed to the ground, recreated 80 years on

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the sale and demolition of Norfolk House. John Martin Robinson re-creates the splendours

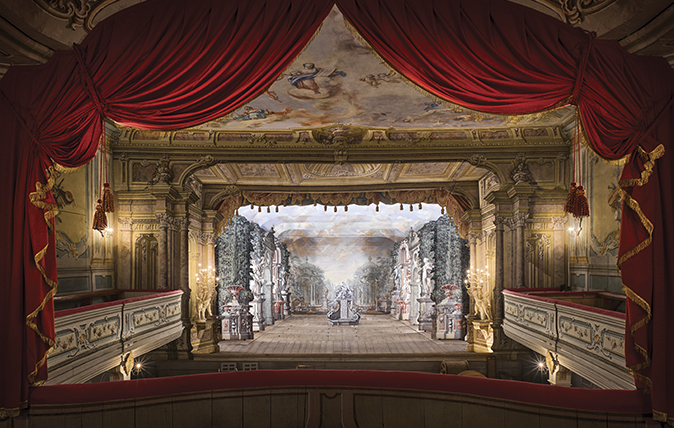

Cesky Krumlov Castle's exquisite theatre: The scene of princely diversion

The object of a heroic recent restoration, the 1760s theatre at Cesky Krumlov carries the modern visitor back into the

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attached

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attachedUpper House in Derbyshire shows why the Kinder landscape was worth fighting for.

By James Fisher

-

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025Wednesday's quiz tests your knowledge on literature, National Parks and weird body parts.

By Rosie Paterson

-

High Wardington House: A warm, characterful home that shows just what can be achieved with thought, invention and humour

High Wardington House: A warm, characterful home that shows just what can be achieved with thought, invention and humourAt High Wardington House in Oxfordshire — the home of Mr and Mrs Norman Hudson — a pre-eminent country house adviser has created a home from a 300-year-old farmhouse and farmyard. Jeremy Musson explains; photography by Will Pryce for Country Life.

By Jeremy Musson

-

Sir Edwin Lutyens and the architecture of the biggest bank in the world

Sir Edwin Lutyens and the architecture of the biggest bank in the worldSir Edwin Lutyens became the de facto architect of one of Britain's biggest financial institutions, Midland Bank — then the biggest bank in the world, and now part of the HSBC. Clive Aslet looks at how it came about through his connection with Reginald McKenna.

By Clive Aslet

-

'There are architects and architects, but only one ARCHITECT': Sir Edwin Lutyens and the wartime Chancellor who helped launch his stellar career

'There are architects and architects, but only one ARCHITECT': Sir Edwin Lutyens and the wartime Chancellor who helped launch his stellar careerClive Aslet explores the relationship between Sir Edwin Lutyens and perhaps his most important private client, the politician and financier Reginald McKenna.

By Clive Aslet

-

Cath Harries — The photographer on a 15-year quest to find the most incredible doors in London

Cath Harries — The photographer on a 15-year quest to find the most incredible doors in LondonBy Toby Keel

-

The extraordinary Egyptian-style Leeds landmark hoping to become a second British Library — and they used to let sheep graze on the roof

The extraordinary Egyptian-style Leeds landmark hoping to become a second British Library — and they used to let sheep graze on the roofThe project has been awarded £10million from the Government, but will cost £70million in total.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

Art, architecture and plastic bricks at Lego House: 'It's as if the National Gallery set up easels and paints next to the masterpieces and invited you try your hand at creating a Van Gogh'

Art, architecture and plastic bricks at Lego House: 'It's as if the National Gallery set up easels and paints next to the masterpieces and invited you try your hand at creating a Van Gogh'The rural Danish town where Lego was created is dominated by the iconic toy — and at Lego House, it has a fittingly joyful site of pilgrimage. Toby Keel paid a visit.

By Toby Keel

-

Restoration House: The house in the heart of historic Rochester that housed Charles II and inspired Charles Dickens

Restoration House: The house in the heart of historic Rochester that housed Charles II and inspired Charles DickensJohn Goodall looks at Restoration House in Rochester, Kent — home of Robert Tucker and Jonathan Wilmot — and tells the tale of its remarkable salvation.

By John Goodall

-

'A glimpse of the sublime': Inside the drawing room of the 'grandest Palladian house in Ireland'

'A glimpse of the sublime': Inside the drawing room of the 'grandest Palladian house in Ireland'The redecoration of the drawing room at Russborough House in Co Wicklow, Ireland, offers a fascinating insight into the aesthetic preoccupations of Grand Tourism in the mid 18th century. John Goodall explains; photography by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

By John Goodall