Broadwoodside: A farm steading in the heart of a magical Scottish landscape

Broadwoodside — the home of Robert and Anna Dalrymple — is a modest farm steading in East Lothian that has been stylishly transformed into the heart of a magical landscape and garden. John Goodall admires the sympathy and humour of the project. Photographs by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

'Ore stabit fortis arare placeto restat’ exhorts an inscription in English — the word divisions wittily bestowing on it the appearance of Latin — in the garden at Broadwoodside. It’s good advice.

The gardens created here over the past 25 years by Anna and Robert Dalrymple are, indeed, a rare place to rest and have become justly celebrated in their own right, attracting a steady stream of visitors and articles. What remains less well known is the house at their heart, which is no less remarkable or delightful.

Broadwoodside is in origin a modest farm steading, formerly part of the Yester estate of the Tweeddale family, set in rolling agricultural land just outside the village of Gifford in East Lothian. The site was anciently occupied and the place name can certainly be traced in the documentary record at least as far back as the 16th century. It’s difficult, however, with the limited evidence available, to say anything about the early form of the steading, which today comprises small buildings of many different dates integrated around a central courtyard.

The earliest surviving structure that can be confidently identified here is a huge ziggurat of stone, the chimney stack of a so-called ingleneuk. The word literally means an ‘ingle’ or fireplace that incorporates ‘nooks’ or seating recesses for warmth within its structure. Ingleneuks are a feature of 17th- and 18th-century Scottish domestic architecture, although they are usually attached to much larger buildings. This example may have been used both to heat the principal living room of an attached house and also for cooking.

It’s likely that the ingleneuk at Broadwoodside was erected in about 1700, when the wider estate was in the process of architectural transformation. Yester House itself was rebuilt from 1699 by John, 2nd Marquess of Tweeddale, after his father, a leading figure in Scottish politics, had toyed with similar plans for at least two decades. One or other of these men, therefore, might well have paid for improvements to Broadwoodside. Whatever the case, the subsequent development of the buildings was closely tied to the changing needs and fortunes of the estate.

This enjoyed a period of particular prosperity in the mid 19th century, when the 8th Marquess of Tweeddale energetically experimented with new agricultural techniques. A large-scale estate map of 1843, made during his period of ownership, delineates Broadwoodside as two rambling lines of buildings to the north and south of a central farm track. His changes included the installation of a steam-driven threshing machine with its own chimney, the latter long demolished. The engine house, added to the south side of the steading, was of cut stone in contrast with the rubble masonry and dressed facings of such other practical agricultural buildings as the granary and cart shed.

Broadwoodside might have been redeveloped in this period with a single, large farmhouse to accommodate a managing family. Instead, the land around it continued to be farmed directly by the estate and it preserved its form, therefore, as a cluster of small buildings.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

These were divided between farm and domestic use and, in 1871, the census records the names of 23 adults and children living here. It was probably to accommodate multiple families that new buildings were added to the east and west, closing off the line of the road that ran through the site in 1843 to form a courtyard.

By 1900, together with the home farm at Yester Mains, Broadwoodside was generating a handsome annual profit of £2,682. This prosperity came to an end during the 20th century, however, with falling agricultural revenues and changing methods of farming. In 1967 the Yester estate was sold, but the tenant family living there, the Bathgates, stayed on. The last of the family, Mrs Bathgate, remained here until the mid 1990s in a cottage without electricity or telephone. In 1997, the empty farm was on the market.

It was at this point that the Dalrymples entered the scene. Mr Dalrymple, a graphic designer, had a long-standing family connection with the area, having grown up nearby at Leuchie (Country Life, January 23, 2023). What follows is so neat that, were it in a novel, it might be condemned as improbable.

Mr Dalrymple had bought a book, Living by Design, in which the designer John Stefanidis describes his stylish transformation of a farmyard in Dorset into a country house in the 1970s. Later that week, driving to Gifford, Mrs Dalrymple saw a for-sale sign on the road that led to Broadwoodside. Undaunted by the extreme dereliction of the buildings, they decided to undertake a similar restoration and bought the property. They had not even been looking for a new family home at the time.

The project that followed, undertaken with the Edinburgh architect Nicholas Groves-Raines, consciously preserved the character of Broadwoodside as a courtyard steading that had evolved over time. Two well-judged additions, however, have helped give presence to its cluster of modest historic buildings.

The first of these was the addition of a corner pavilion with a bell-shaped slate roof, a form beloved by the Scottish Arts-and-Crafts architect Robert Lorimer. With its ochre walls and crowning weathervane, this forms an eye-catcher within the wider landscape. Second, Mr Groves-Raines dignified the entrance to the courtyard with a gatehouse. Over the gate is a dovecote and cupola.

Stepping through the gate, the visitor enters an internal, courtyard garden divided into two distinct compartments by a low wall and steps. These feel like additional rooms to the house, with the character of each space loosely relating to its adjacent buildings. The area closest to the gate is like a garden hall, laid out with a bold chequerboard of cobbles, lawn and topiary in yew, box and maple (Fig 1). Incorporated within the chequer pattern is a timber-frame birdcage, the home of the family’s pet African grey parrot, William (Animal magic, October 16, 2019).

There is also a homemade sculpture of oak cubes and glass rods supporting a sphere of crystal. When the sun shines, the crystal focuses its beams on the oak pedestal, gradually burning it away. Sculpture — sometimes simply in the form of an object presented in a striking way — is an important feature both of the house interiors and the garden.

To the right of the courtyard are the principal rooms of the main house and the front door, sturdily built of oak with iron studs. The doorway itself is a historic opening, but it incorporates a new lintel inscribed ‘Broadwoodside 2000’, the lettering picked out in gold. To either side are the initials of the Dalrymples. The second of these initials, ‘AD’, is thereby turned into a pun, referring both to Anna Dalrymple and to the date, as the abbreviation of ‘the year of Our Lord’, anno domini. It’s one of countless playful details that are a feature of the inscriptions found throughout the house and which reflect Mr Dalrymple’s experience as a graphic designer.

The front door leads into a staircase hall, an upper floor having been contrived within part of the courtyard. Beyond is a dining room and kitchen (Fig 3), the latter occupying the shell of the building that once housed the steam threshing machine. It enjoys views both outwards over the countryside and up towards the garden compartments above the house. Clearly visible from it is a gate in brilliant vermillion that leads to the understated burial area of the family’s pets. Cut in the gate piers, which support small urns, are the explanatory words ‘going to the dogs’.

Opening from the dining room (Fig 7) through the length of the south side of the courtyard is an enfilade of the drawing room, library and nursery beyond.

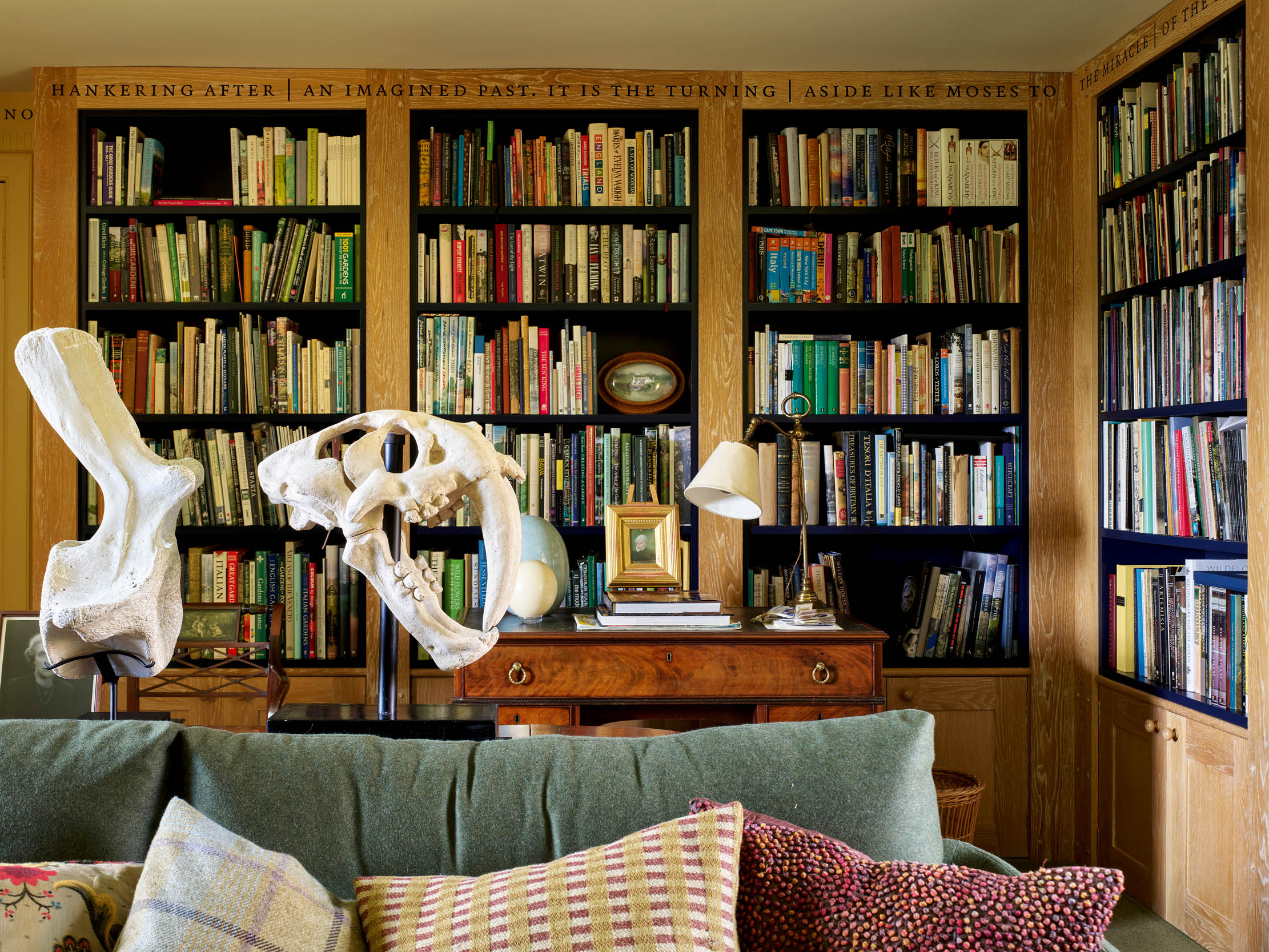

The use of colour and materials is striking throughout. In the drawing room, for example, the fireplace is made visually dominant by the use of blue and gold tiles and the scale of the interior with its open roof is softened with Madagascan shawls draped over the cross-timbers (Fig 4). In the library, the shelf frames are of limed oak lined in black-painted wood. This gives the illusion that the books they contain hang in the air (Fig 6). Around the cornice runs the text of The Bright Field by R. S. Thomas.

Returning to the central courtyard, the second garden compartment comprises a lawn enclosed by flowerbeds. At the intersection of the paths that divide it into quarters is a large copper (Fig 5). The enclosing buildings are subsidiary to the main house and include Mr Dalrymple’s office in the upper floor of the new pavilion, guest rooms and also an open hall for events. The roof over this latter space facing into the courtyard is covered in a chequerboard of terracotta and black tiles. There is also a passage (or pend) through the range that closes off the courtyard to a kitchen and cutting garden beyond. This area has as its centrepiece a pool enclosed by willows. The gardens were described for COUNTRY LIFE on February 22, 2007, although they have continued to mature since then.

One of the most magical qualities about the place is the way the garden connects to the landscape beyond. An avenue of hornbeams descends from the new pavilion and there are walks through the surrounding woods and fields. These are again dotted with sculptures and inscriptions that intrigue or amuse and there is a lake with a timber sitooterie. To the south-west is the rescued portico of Strathleven House, Dumbartonshire, which presides in the landscape like a temple. The view back to the house from the portico bestows on the composition the spirit of a Roman villa nestling in the landscape (Fig 2).

Broadwoodside is a remarkable achievement. It is a country house that is both memorable and noteworthy, without ever falling into the trap of architectural pretension. That is perhaps because the humble origins of the steading still shine through the transformation to lend texture and interest to the buildings. No less remarkable is the way that the house graduates into the garden and the garden into the landscape. This is a house that feels not merely at home in its setting, but born from it. Finally, there is the delight of the place, enlivened with colour, inscriptions and beautiful things. If Arcadia possessed a country house, surely this would be it.

Broadwoodside, East Lothian, opens for Scotland’s Gardens Scheme on July 9 and by appointment (www.broadwoodside.co.uk)

Leuchie: The house and garden where the 1960s meet the 1690s

A Modernist home created during the 1960s within the walled garden of a historic house stylishly blends the contemporary and

The WW2 naval base set to become an incredible clifftop home near Edinburgh

Gin Head, near North Berwick, was instrumental in our success of the D-Day landings.

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.