Benington Lordship: From medieval castle to comfortable home – and back again

The Benington Lordship in Hertfordshire started life as a medieval castle, but has been transformed over the centuries into a comfortable house with ambitious neo-Norman additions and continues to thrive under owners Richard and Susanna Bott.

When Ambrose Proctor of Ware, Hertfordshire, died in 1810, he left his considerable fortune (derived from the malting industry) to four great-nephews. The problem was that much of his estate consisted of property spread over a number of small farms in eight separate parishes, making it both inconvenient and inefficient to manage. It took an Act of Parliament, in 1824, to authorise the sale of the land in order to achieve ‘a more connected and convenient estate’.

With his portion, the eldest of the beneficiaries, George Proctor, a solicitor, purchased the manor of Benington, eight miles north-east of the town of Ware, from John Chesshyre. His three unmarried brothers took up residence at Thunder Hall, Ware.

‘Lordship’ is the name given to a number of Hertfordshire manor houses. The Saxon manor was granted by William the Conqueror to Peter de Valognes, sheriff of Hertfordshire and Essex in 1086, who made Benington his caput. It was presumably he who constructed the original earthworks, which were later fortified in stone, probably by his son Roger in the 1130s. There was a curtain wall and deep curved moat on three sides, with steeply sloping ground to the west, and an outer bailey, protected by earthworks, to the east.

In 1176–77, 100 picks were purchased for ‘levelling the tower of Bennington’ on the orders of Henry II. The foundations of the keep or tower in question – roughly 44ft by 41ft with a subsidiary entrance tower or forebuilding – survive. It’s unclear, however, whether demolition went ahead, as the castle is recorded as strongly garrisoned in 1193.

Shortly afterwards, it came into the possession of Robert Fitzwalter by marriage. He was outlawed by King John in 1212 and then the castle really was overthrown.

The manor was owned in the 14th century by John de Benstede and his heirs and, later, by the Earls of Essex, who, in 1614, sold it to Sir Julius Caesar, a distinguished lawyer and politician and son of the Italian-born physician to both Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth.

It was his descendant Charles Caesar, MP for Hertford and then Hertfordshire on five separate occasions between 1701 and 1741, who built the present house in about 1700 on the site of a Tudor predecessor. This new building was 2½ storeys high, of red brick, with a south front of chequered red brick facing the church, although, until at least the middle of the 18th century, there was a range of buildings between the two.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The Caesars did not, however, live at The Lordship, which may have been intended as a dower house, but at Benington Place, on the other side of the village. After Charles Caesar’s death in 1741, the estate became the property of John Chesshyre. Soon afterwards Benington Place burnt down and, although it was rebuilt, the Chesshyres made their home at The Lordship.

It was perhaps the castle ruins, as much as the house, that appealed to Proctor when he bought the estate in 1826. He was establishing himself as a country gentleman and landowner and may have liked the sense of history that the castle provided, which was further enhanced by his appointment as High Sheriff in 1837.

Certainly, when it came to improving the house, it seems to have been the castle that took most of his attention. No ruins are shown on an estate map of 1743 (which marks the house itself as ‘Lordship Farm’), although the outline of the moat, enclosing gardens to the south and east of the house, is clearly visible.

It seems likely, therefore, that what remained of the keep had become buried over the years; whereas most of the surviving walls, which now stand up to a height of about 8ft, are of flint rubble, there are small amounts of Barnack ashlar at the base, suggesting that these were covered over (and thus survived) at a time when the facing stone was stripped from the rest of building and reused elsewhere.

What is clear is that, in 1835–38, the castle ruins were incorporated into what Nikolaus Pevsner described as a ‘neo-Norman fantasy’ to create a new entrance courtyard to the Queen Anne house, giving the impression that much more of the castle survived than was the case.

The contractor for the work was James Pulham and it is described and illustrated in a promotional book, Picturesque Ferneries and Rock-Garden Scenery, written by his son (also James) about 40 years later. The elder James Pulham came from Wood-bridge, Suffolk, where he worked for a local builder, William Lockwood, who had developed a form of Portland-stone cement that provided a fair imitation of stone.

Pulham and his brother Obadiah continued to work for Lockwood as architectural modellers after he expanded his business in London and, by 1826, Obadiah’s work had come to the attention of Thomas Smith, from 1837, Hertfordshire’s county surveyor. When, in the 1830s, Smith came to build a folly tower in the grounds of his own house in Hertford – a mock ruin with cement ‘stonework’ – there is little doubt that the Pulhams carried out the work and it is equally likely, although not documented, that Smith was the architect for the work at Benington Lordship.

The fame of Pulham and his descendants came to surpass that of Smith: the artificial stone, known as Pulhamite, manufactured in Broxbourne until the Second World War, was renowned, being used particularly to create artificial rockeries and other garden features in country houses across England (including Sandringham and, after Edward VII’s accession, Buckingham Palace). The material was also favoured for cliff walks at seaside resorts such as Ramsgate, Folkestone and Lytham St Annes.

The choice of Norman as the style for most of the new work was, no doubt, largely prompted by the age of the castle, but, at this time, it was generally fashionable. Much of the decorative detailing seen at Benington can be found in works such as Essays on Gothic Architecture, published by Josiah Taylor in 1800, which popularised drawings of Norman architecture by William Wilkins first published in 1796.

In addition, perhaps the greatest and most ambitious of all neo-Norman domestic buildings, Thomas Hopper’s Penrhyn Castle, was nearing completion at the same time as Benington.

Near St Albans is one of the earliest neo-Norman churches in the country, George Smith’s St Peter’s, London Colney, of 1824–25, and Thomas Smith would go on to build (with the younger James Pulham) the neo-Norman church at West Hyde in 1844–45.

The work at Benington Lordship consisted of adding, along the east side of the house, a single-storey entrance corridor that opened into a staircase hall (the position of the original entrance to the house is not known, but was probably on the north side).

Opening off the north end of the corridor was a large dining hall, with a north-facing window of intersecting neo-Norman tracery, and, beyond it, a smoking room with a similar, smaller window.

To the east of the dining hall, a large gateway was constructed, with a semi-circular archway and round towers with machicolations and the ruins of battlements. Under the archway are the impaled arms of Proctor and his wife, Elizabeth Hale, and masonic emblems. Over it, on the outer side, is an obscure heraldic device and, on the inner side, a cement relief panel with a scene of monks paying homage to a king, perhaps depicting a supposed episode in the history of the castle.

The facing of all the neo-Norman work is a mix of flint rubble and cement modelled in imitation of rough-hewn blocks of stone, but, in several places, the red-brick carcase shows through; the detailing is also executed in cement. The windows and door of the corridor, by contrast, are in stone and in the Perpendicular style with rectangular tops, although some of the hoodmoulds have headstops characteristic of Pulham’s work.

The glass in these windows, and in the staircase window above, includes a picturesque assortment of old stained glass, mainly of German or Flemish 17th-century type.

The courtyard is enclosed with a fake ruined curtain wall that curves round to join up with the real ruin of the keep and partway along it is a summer house, like a ruined tower, also with a semi-circular neo-Norman arched entrance. Inside it is a marble tablet with a Greek inscription commemorating a slave, part of a tomb found on the plain of Troy by Capt the Hon John Gordon and given by him to Proctor in 1832.

Proctor did not live long to enjoy his new castle. He died in 1840 and was succeeded by his son Leonard. It is not certain which of them built the stables to the north, but the Pulhams’ continuing involvement is apparent. The west range of the otherwise unremarkable building, which contains the main stalls, has an open timber roof with tracery above the collar-beams; the principals rest on winged horses made of cement, almost certainly the work of Obadiah Pulham, who executed similar beasts at Thunder Hall.

Proctor leased out Benington Lordship not long before his death in 1899 and, in 1905, it was purchased by Arthur F. Bott, an engineer from an old Staffordshire family, who had prospered building railways in India, and his wife, Lilian.

The following year, major alterations and additions were made to the Queen Anne house by the architect E. Arden Minty, of London and Petersfield, Hampshire (he also, in 1907, restored the tower of Benington church). The dining hall was subdivided to form a kitchen with scullery and larder (the partitions have since been removed, but it still has a false ceiling) and the smoking room was converted to a servants’ hall.

The staircase hall was remodelled and the two south-facing rooms of the original house became the morning room and dining room. On the west side, a two-storey range was added, subservient to the old house, but in sympathetic style, with modillion eaves cornice, attic dormers and a small pediment on the west front.

This addition provided a large drawing room and a billiard room (now kitchen) with smoking room at one end, all opening onto a verandah with a lean-to roof on Tuscan columns – perhaps inspired by memories of India? It looks down over the gardens and ponds in the valley below and is a delightful addition to an already lovely house.

Of equal importance were the improvements that the Botts made to the gardens, which are, for many people, what Benington Lordship is best known for – it was one of the pioneer gardens that opened for the National Gardens Scheme in 1927. The gardens were enlarged, a ha-ha was built between them and the park and the drive was altered so that the entrance was from the centre of the village, with a lodge.

The gardens were sympathetically restored by the Botts’ grandson Harry and his wife, Sarah, from 1970, and continue to thrive under the care of Richard and Susanna Bott.

Benington Lordship is open to the public and holds events during the year, including a snowdrop celebration and a chilli festival – see their Instagram page or Facebook page for more information, or see their listing on the National Garden Scheme website.

The Castle of Mey: Inside the Queen Mother's beloved home

A visit to Scotland in the first months of her widowhood encouraged The Queen Mother to buy and restore a

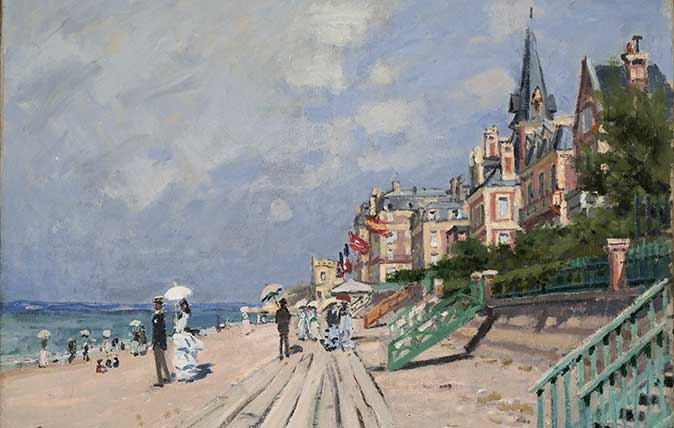

In Focus: The paintings which show Monet's genius for architecture as well as nature

Think of Monet and you think of reflections and nature, but his works included huge amounts of architecture and other

Credit: Chris Curl

A delightful 'medieval' castle for sale that was built by one of the 20th century's finest architects

You'd think it was hundreds of years old, but Castell Gyrn is actually a creation of the late 20th century

Cesky Krumlov: Inside one of Europe’s greatest castles

Cesky Krumlov Castle was extravagantly remodelled in the 18th-century. In the first of two articles, John Goodall considers its development

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric village

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric villageA romantic experiment surrounded by the natural majesty of North Wales, Portmeirion began life as an oddity, but has evolved into an architectural phenomenon kept alive by dedication.

By Ben Lerwill

-

Seven of the UK’s best Arts and Crafts buildings — and you can stay in all of them

Seven of the UK’s best Arts and Crafts buildings — and you can stay in all of themThe Arts and Crafts movement was an international design trend with roots in the UK — and lots of buildings built and decorated in the style have since been turned into hotels.

By Ben West

-

High Wardington House: A warm, characterful home that shows just what can be achieved with thought, invention and humour

High Wardington House: A warm, characterful home that shows just what can be achieved with thought, invention and humourAt High Wardington House in Oxfordshire — the home of Mr and Mrs Norman Hudson — a pre-eminent country house adviser has created a home from a 300-year-old farmhouse and farmyard. Jeremy Musson explains; photography by Will Pryce for Country Life.

By Jeremy Musson

-

Sir Edwin Lutyens and the architecture of the biggest bank in the world

Sir Edwin Lutyens and the architecture of the biggest bank in the worldSir Edwin Lutyens became the de facto architect of one of Britain's biggest financial institutions, Midland Bank — then the biggest bank in the world, and now part of the HSBC. Clive Aslet looks at how it came about through his connection with Reginald McKenna.

By Clive Aslet

-

'There are architects and architects, but only one ARCHITECT': Sir Edwin Lutyens and the wartime Chancellor who helped launch his stellar career

'There are architects and architects, but only one ARCHITECT': Sir Edwin Lutyens and the wartime Chancellor who helped launch his stellar careerClive Aslet explores the relationship between Sir Edwin Lutyens and perhaps his most important private client, the politician and financier Reginald McKenna.

By Clive Aslet

-

Cath Harries — The photographer on a 15-year quest to find the most incredible doors in London

Cath Harries — The photographer on a 15-year quest to find the most incredible doors in LondonBy Toby Keel

-

The extraordinary Egyptian-style Leeds landmark hoping to become a second British Library — and they used to let sheep graze on the roof

The extraordinary Egyptian-style Leeds landmark hoping to become a second British Library — and they used to let sheep graze on the roofThe project has been awarded £10million from the Government, but will cost £70million in total.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

Art, architecture and plastic bricks at Lego House: 'It's as if the National Gallery set up easels and paints next to the masterpieces and invited you try your hand at creating a Van Gogh'

Art, architecture and plastic bricks at Lego House: 'It's as if the National Gallery set up easels and paints next to the masterpieces and invited you try your hand at creating a Van Gogh'The rural Danish town where Lego was created is dominated by the iconic toy — and at Lego House, it has a fittingly joyful site of pilgrimage. Toby Keel paid a visit.

By Toby Keel