Beeleigh Abbey: An incredible medieval house that's barely altered since Henry VIII's Dissolution of the monasteries

David Robinson looks at Beeleigh Abbey — the Essex home of Catherine and the late Christopher Foyle — an exceptional and little-known survival of the Premonstratensian canons, one of the less-familiar monastic and religious orders of medieval Britain. Photographs by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

It’s now a full century since Beeleigh Abbey first appeared in the pages of Country Life, back on September 30, 1922. Christopher Hussey, the Architectural Editor at that time, was doubtless invited to visit the house by Richard Edwin Thomas, its enthusiastic new owner. In that same year, Thomas had already published a handsome little Arts-and-Crafts-style volume on Beeleigh, under his own imprint. It was from this volume that Hussey derived much of the material in his article, but this remarkable and little-known site richly repays revisiting.

Beeleigh is no grand pile still bearing the name ‘abbey’, yet with little visible evidence of its medieval past. Nor is it one of those skeletal ruins that leave the visitor disorientated and struggling to understand what they see. It is something much more unusual: a complete and coherent fragment of a medieval religious house, where the internal arrangements — including a superb early-16th-century roof — have barely been altered since the time of the Dissolution.

The Abbey of St Mary and St Nicholas at Beeleigh was founded towards the end of the 12th century for a community of Premon-stratensian canons, named after the mother house of their order, Prémontré (Aisne), in north-eastern France. It was here, in an isolated valley in the forest of Saint-Gobain, that the movement’s inspirational but restless leader, St Norbert of Xanten (d. 1134), had settled with a small group of disciples in 1121.

Norbert was an instinctive and charismatic preacher, and a tireless proponent of church reform, but he was no administrator. Indeed, it was left to his principal follower, Abbot Hugh de Fosses (1128–64), to produce a constitutional framework for the spiritual ideals of the early community. In this regard, the Premonstratensians borrowed much from the Cistercians, although they soon emerged as a distinct and fully fledged religious order.

Popularly known as the ‘Norbertines’ or the ‘White Canons’ (after their bleached woollen habits), the Premonstratensians were extraordinarily prolific, with eventually more than 500 abbeys situated in almost every corner of the Christian West. On this side of the Channel, the first plantation was made at Newhouse in Lincolnshire, in about 1143. In line with the order’s statutes, many of the subsequent British houses — close to 40 in all — were located in secluded rural settings, such as Easby in North Yorkshire, Talley in west Wales or Dryburgh in the Scottish Borders.

Before 1172, Newhouse despatched a group of canons to establish a further abbey at Great Parndon in Essex. For whatever reason, the location proved unsuitable and, in 1180, the fledgling community migrated about 30 miles due east, to Beeleigh. With the support of Robert Mantell (d. 1190), lord of Little Marlow and sheriff of Essex, the canons were settled on the river Chelmer, a short distance upstream from the market town of Maldon.

An important charter confirming Mantell’s gifts to Beeleigh — specifically naming him as the founder — was granted by Richard I in 1189. Further endowments of property were to follow through the 13th century and beyond, both from high-born patrons and from those of more modest means. In 1253, for instance, Lady Hawise de Neville (d. 1269) and her husband, Sir John de Gatesden, made a sizeable gift to the community, in return for which a canon was to celebrate a daily Mass for them and their heirs.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

By then, Beeleigh was attracting a degree of fame through its association with a former bishop of London, Roger Niger (d. 1241), who was venerated as a saint. Perhaps born locally, Niger appears to have asked for his heart be buried in the church. Hence, in 1249, William de Fancourt and his wife, Rose, granted the canons a plot of land, in return for which — during certain Masses — they were to light a candle ‘before the heart of St Roger for ever’.

We might infer that construction of the abbey church was put in hand in about 1180, when the community moved to Beeleigh. It would be surprising, then, if the work had not been finished before the mid 13th century. There is every indication, too, given the surviving architectural evidence, that early progress was made with all three principal ranges of buildings surrounding the cloister. Alas, the church has entirely disappeared (Fig 3), although we shall look at documentary evidence for its arrangements later. The cloister, meanwhile, definitely lay to the south of the nave.

As Beeleigh is encountered today, by far the most prominent survival of the medieval abbey is the long range that flanked the east side of the cloister (Fig 1). Originally attached to the south transept of the church, at ground level it housed the sacristy, the chapterhouse, the inner parlour and the canons’ day room. Above, almost the entire first floor was occupied as the canons’ dormitory, linked at its southern end to their communal latrine.

Two of the ground-floor spaces are perfect embodiments of comparatively restrained early 13th-century architecture, namely the chapterhouse and the day room. The former was entered from the cloister by way of an unusual double doorway, featuring ‘dog-tooth’ ornament and moulded arch heads (Fig 7). Inside, three slender octagonal piers divide the room into two aisles, emphasising its east-west alignment. Springing from the piers and wall corbels, elegant moulded vault ribs form four-part bays. In four of the bays there are foliage bosses at the intersection of the ribs (Fig 5). Two of these ornament the privileged space where the abbot would have sat enthroned to preside over chapter meetings.

The handsome four-bay chamber at the southern end of the range is currently occupied as a comfortable sitting room. Variously described as the dormitory undercroft or the calefactory (warming house), it might equally be regarded as the canons’ day room (Fig 2). It is of similar proportions to the chapterhouse and is, again, arranged in two aisles, but here the central row of polished Purbeck-marble piers — including the capitals and bases — are circular. The vault ribs were of a simpler design, reflecting the hierarchy between the two spaces.

Set between these two grand rooms, a less imposing barrel-vaulted chamber ran through the width of the range. This is likely to have been the inner parlour, where the canons might speak on essential matters without breaking the silence of the cloister. Given that, in the 13th century, there were doorways at both ends, it may also have provided access to the canons’ infirmary, situated further to the east. Parts of a medieval painted frieze, with foliate scrollwork, survive on the walls.

The canons’ dormitory ran above all three spaces, continuing northwards over the now-lost sacristy, with its gable end eventually meeting the south transept of the abbey church. Now, however, we find the room curtailed by north and south partitions, introduced after the Dissolution. In its original 13th-century form, the dormitory would have been a single open chamber, with the canons’ beds positioned down either side.

Today, there is only a small surviving fragment of the range that once flanked the south side of the cloister. Primarily, it housed the canons’ refectory at first-floor level, an arrangement that occurred at many other Premonstratensian houses. Indeed, it’s been suggested that this was a deliberate evocation of the Cenaculum, the upper room in which the Last Supper took place. Following the example of St Norbert, the canons believed in an Apostolic approach to religious life.

In the later Middle Ages, although the Beeleigh community remained moderately wealthy, stability was rocked when Abbot Thomas Cokke (1384−1405) evidently became entangled in a conspiracy against Henry IV. Although pardoned, Cokke’s troubles were not at an end. In the spring of 1405, he was poisoned, possibly by one of his own canons. The unfortunate abbot took 11 weeks to die.

Discipline and order under the penultimate abbot, Thomas Skarlett (about 1481−1511), was much improved. Abbot Skarlett was aware, for example, of maintaining good relations with lay elites, notably Beeleigh’s then chief patrons, the Bourchier family. Henry Bourchier, 1st Earl of Essex, was buried in the Lady Chapel in 1483, as was his wife, Isabel. Earl Henry’s fourth son, Sir John (d. 1495), asked in his will to be buried ‘next my lord fader and my lady moder’ and for a canon ‘to singe in our lady chapell for me and for my wife’.

It was in Abbot Skarlett’s time, too, that Beeleigh was visited, no fewer than five times, by Richard Redman, Abbot of Premonstraten-sian Shap, and the order’s visitor and commissary general for Britain. The records of these visits reveal high standards of observance at the house, in spiritual and temporal matters.

In 1488, for example, Redman noted a community ‘governed for God’s praise’, with ‘perfect harmony between head and members’. The records also show that Abbot Skarlett successfully cleared his house of all debt. In October 1500, Redman was especially impressed with what was described as the beautiful construction work on the abbey church, including sumptuous new windows, again done without incurring any debt.

Throughout the building as a whole, in fact, we find evidence for various later-medieval modifications to the original 13th-century abbey fabric. The eastern windows in the chapter house, for instance, were altered in the 14th century, whereas the day room was significantly transformed in the following century, with the introduction of large traceried windows in the east wall, together with a prominent new fireplace (Fig 4).

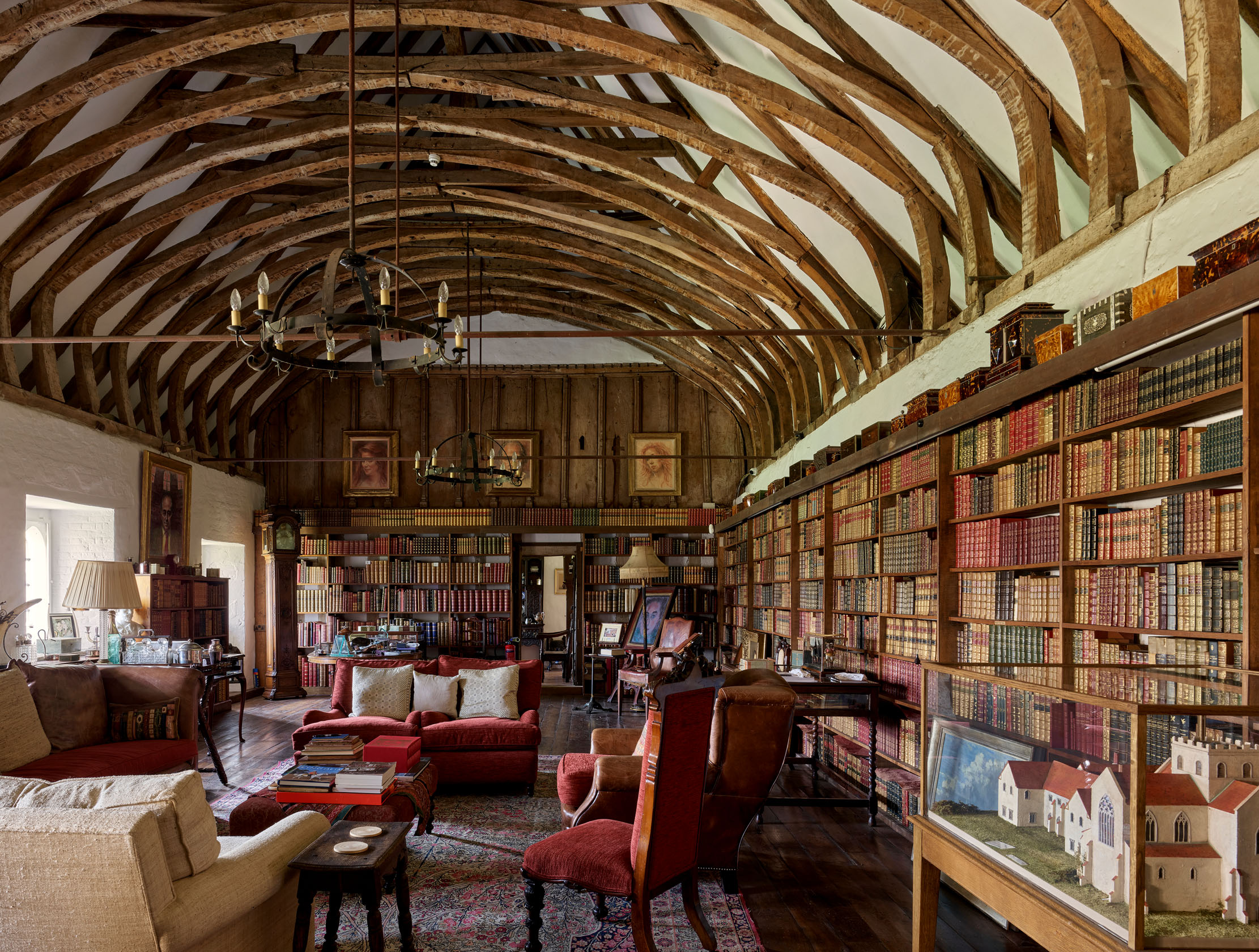

In the canons’ dormitory (Fig 6), and in their refectory, the scale of the late-medieval remodelling was also extensive, with new roofs built over both spaces. Tree-ring dates suggest that the dormitory roof was raised in the period 1511−39, whereas the refectory roof must have been constructed soon after 1513, only decades before the Dissolution.

The impressive dormitory roof comprises 32 pairs of rafters, linked by so-called collar-beams and curving braces. The resulting wagon-vault was possibly ceiled. The works here also featured new windows, at least in the east wall, with external brick surrounds. If not before this date, the interior of the dormitory was probably now divided into individual cells for each canon.

In 1535, Beeleigh’s net annual income was assessed at almost £158, which was not insubstantial, but still made it vulnerable to closure under the 1536 Act of Suppression. In June of that year, royal commissioners made a detailed inventory of all the abbey buildings and their contents, the church being of particular interest. In the presbytery, for instance, the high altar was of alabaster. Flanking this, perhaps on the south side, the Lady Chapel (where the Bourchiers were buried) housed a pair of organs. In addition, the Rood Chapel was presumably in the nave, the Jesus Chapel could have been located in a north aisle, and St Catherine’s Chapel possibly extended from the north transept.

Effectively, the compilation of the 1536 inventory marked the end of Premonstratensian life, but the story of Beeleigh itself was far from concluded. In next week’s article, we shall pick up on some of the many events in the centuries after the Dissolution.

Sherborne Abbey's stained glass: The spectacular Victorian addition to a building with 1300 years of history

The spectacular stained glass at Sherborne Abbey is only part of what makes this building one of the grandest in

Almshouses: What they are, how they were created and why they're still relevant in the 21st century

Built for the clergy, the military, retired estate workers and, most commonly, for the poor, almshouses are as important today

-

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Country Life