Australia House: The story of Australia's unforgettable outpost in the heart of London

An imposing home for the newly federated Commonwealth of Australia sought through its design and materials to celebrate themes of union with Britain and national self worth, as Prof G. A. Bremner explains.

Once seen, Australia House — occupying the eastern point of the Aldwych island site on the Strand — is not easily forgotten. Unlike the rambling Gothic pile of the Royal Courts of Justice by George Edmund Street nearby, it is not a huge building. Its powerfully articulated façade, conspicuously paraded on three sides, nevertheless makes for an impression that belies its stature. This attention-seeking demeanour, as it were, was intentional. Designed in 1911 by the Scottish architectural partnership of Alexander Marshall Mackenzie and his son, Alexander George Robertson, Australia House was designated the home of the High Commission of the recently federated Commonwealth of Australia (1901).

The architects’ goal was to create a building, ‘architecturally worthy of the headquarters of the Commonwealth in the capital of the Empire’. Being a newly independent Dominion, Australia was, indeed, keen to make its presence felt in the Imperial capital. The youthful nation believed it had much to offer and saw a magisterial piece of architecture as an effective way of advertising its importance to the continued primacy and economic prosperity of Greater Britain on the world stage. This was an entirely fitting aspiration, as the events of the First World War would prove.

By the time of the building’s completion and official opening in August 1918, the fledgling nation of Australia had voluntarily answered the call of ‘King and Country’. Having made huge sacrifices towards the Allied victory, Australia had proven its loyalty and Australia House stood as a grandiose emblem of its steadfast allegiance. The great bronze sculpture of Phoebus Driving the Horses of the Sun by the Australian sculptor Bertram Mackennal was yet to take pride of place above the main entrance, but, as the Architectural Review opined, there could hardly have been a more fitting subject in ‘this day of the fame of the Australian soldier and his crest of the Rising Sun’.

Planning the building was no straightforward task. As Australia had been six independent crown colonies before federation, a degree of rivalry existed between them. Indeed, even following political union, these states — as they became — jealously guarded their limited independence and sense of identity. This created a tension in the requirement of each state to be represented in the building, with their own office space. This was exacerbated by the fact that the government of Victoria already had its own premises at the south-west corner of the site (Victoria House), built in 1909. Tall and slender, this building was designed by Alfred Burr, with the assistance of Norman Shaw, in a heavily rusticated Baroque Classicism. It had been envisaged as the first instalment of a much larger building encompassing the other Australian states. But, with a change of strategy, it presented something of a challenge, both politically and architecturally. Ultimately, the problem was solved by removing the existing gable and turret and remodelling the roof, enabling its seamless integration with the new and larger Australia House.

The exterior of Australia House (Fig 3) is of Portland stone, on a base of light-grey trachyte from Mount Gibraltar in New South Wales. The tripartite division of rusticated lower section, rising through coupled giant-order columns, up to a strong entablature with projecting cornice, is topped with a mansard roof decorated with elaborately worked copper ridge caping and mouldings. As a whole, the ensemble makes for what was described in the architectural press at the time as a building ‘full of masculine strength and vitality’.

Such parlance was understood as signalling an architecture of intent and one replete with wider political connotation. Indeed, the combination of materials was itself significant in this regard, capturing symbolically the idea of common bond: Australia, once a collection of separate crown colonies, now independent, still cleaves happily to the ‘mother country’ in supporting shared cultural and political values. Moreover, trachyte was a stone commonly employed in Italy during the time of the Roman Empire. Thus, combined with a style of architecture described by the architects as ‘Roman’, the building certainly struck something of an imperial chord. In this sense, Australia House was a masterstroke of architectural diplomacy, at once a statement of national self worth and symbol of cooperation and union.

The pairing of British and Australian materials on the exterior is carried through inside. As visitors enter the building, they are greeted by a magnificent, elongated vestibule (Fig 7), beyond which lies a large space that once served as an exhibition hall (Fig 1). Both spaces are lavishly decked in 1,200 tons of veined and mottled Australian marbles from Buchan in Gippsland, Victoria, and Caleula in New South Wales. This marble has been beautifully worked by H. G. Jenkins & Sons of Torquay in the same, ebullient style of Classical architecture as the exterior. Its effect is marvellously enhanced through gilding and a considerable amount of bronze decoration in the form of metopes and rosettes, wreaths and trophies.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Visible here, too, are Roman shields, continuing the imperial theme from outside. In the trophies can be identified devices referent of Australian industry, such as mining picks and heads of wheat; whereas the triglyphs in the frieze surrounding the hall depict rams’ heads representative of one of early Australia’s greatest industries, wool. The keen eye will also spot other flora and fauna indicative of the country, including grapes and pearls, not to mention the kangaroo and emu, which appear on the Australian coat of arms. Indeed, Australian plants and animals are found poking out from behind almost every corner.

The public concourse — including vestibule, main stair (Fig 5) and hall — was illustrative of the abundance and fecundity of this resource-rich land. As potential immigrants and entrepreneurs came to view the exhibits and absorb their tale of antipodean opportunity, the surrounding architecture did its silent, but persuasive work. So impressive was this space that it was considered at the time to be one of the finest of its type in the country.

Opening directly above the vestibule area, on the first storey, is a glass-covered rotunda (Fig 4), drawing the eye up almost immediately as one enters the building. Apart from shedding light deep into the space beneath, this rotunda acts as a transitionary zone between the High Commissioner’s office (Fig 2), at the very front of the building, and the library-cum-conference room above the exhibition hall. The latter of these two spaces, stately in appearance, is large and quadrangular in shape. As in the hall beneath, it is decorated with Caleula marble columns, only this time in pilaster form with gilt capitals (Fig 6).

The timber panelling, as with nearly all the timberwork in the building, comprises native Australian wood, in this case Moreton Bay chestnut (Castanospermum australe), prized for its swarthy and grained appearance. The interiors of the building are also characterised by extensive use of metal and bronze componentry, such as doors, windows and balustrading, including that on the stairs and around the rotunda. In the upper levels and on the stairs, extensive use has been made of the distinctive creamy-white marble from Angaston in South Australia.

The metalwork emphasises the ‘French’ element of the design, broadly reflecting Louis XIV taste. It also provides further opportunity for ornament, with symbolism appropriate to the building’s purpose and meaning woven through. On the rotunda balustrading, for example, one can find gilt-bronze motifs of the seven-point star, which appears on the Australian flag (and coat of arms), surrounded by heads of wheat; whereas above the main entrance door in iron is positioned a gilt-bronze trophy modelled with a winged head of Minerva surrounded, among other things, by floral motifs depicting Australia’s emblematic native plant, the wattle.

Although the architecture is distinctly historical in style, the building represented thoroughly modern construction. Built by Dove Brothers of Islington, it is of steel frame with hollow brick and reinforced concrete flooring, which, by the end of the first decade of the 20th century, was becoming standard for large building projects in London. Electric lighting and inter-office telephone communications were installed throughout. In addition, two Waygood-Otis electric passenger lifts were installed, with a speed of 300ft per minute. An innovative system of heating the building was also fitted. This ‘panel’ system was effectively hidden from view behind the marble and plaster walls and skirting, from which heat radiated. The total cost of the building, as one might expect, was high, coming in at about £1 million (roughly £57 million in today’s money).

Returning to the exterior, we find the main entrance flanked by two large and conspicuous groups of sculpture. These are by the British-born Australian sculptor Harold Parker, who, upon returning to his homeland in 1896, worked with the likes of Hamo Thornycroft and Thomas Brock. The groups, executed between 1915 and 1918, are very much in the so-called New Sculpture style of the period, and depict (left, facing the entrance) The Prosperity of Australia and (right) The Awakening of Australia.

These are both pyramidal compositions, with leading female allegorical figures. The figure representing ‘prosperity’ is seated, with right arm outstretched and left holding a dove to her chest. With a cornucopia positioned directly beneath her outstretched arm, the idea would appear to be that Australia is a land of peace and plenty. The masculine figures below hold the fleece of a ram and a sheaf of wheat, indicative of Australia’s primary industries. The opposing group is represented by a youthful woman rising as if from slumber, shedding her night attire and stretching her limbs. The symbolism is clear; beneath are positioned a dying explorer and his companion (holding a map), representative of the opening up of the Australian interior or ‘outback’.

Later, in 1923, would come the magnificent Phoebus Driving the Horses of the Sun by Mackennal, Australia’s most eminent sculptor working in London during the period, placed high on the cornice above the main entrance. Here, it faces along the Strand and Fleet Street, a prominent feature of the Imperial ceremonial route — recently improved by the realignment of the Mall — that stretched from St Paul’s Cathedral to Buckingham Palace.

Australia House was widely acclaimed as a successful building and it remains the home of the Australian High Commission to this day. The model it presented at the time was replicated by Britain’s other leading colonial Dominions and territories. Nearby, on the same Aldwych island site, rose India House (1926–30), to designs by Herbert Baker. Not long after would appear South Africa House (1931–33), on Trafalgar Square, also designed by Baker (with Alexander Thomson Scott). Across from it, on the other side of Trafalgar Square, the Canadian government acquired the original premises of the Union Club and Royal College of Physicians, completing a refurbishment in 1925 to house the Canadian High Commission.

As subsequent events have shown, what this sequence of ‘dominion houses’ signalled, in fact, was the slow, but steady decolonisation of the British Empire, the first step in what would ultimately become the British Commonwealth of Nations we know today. In this sense, Australia House is an historical monument, as well as an architectural one.

Curious Questions: Why do Australians call the British 'Poms'?

With England about to take on Australia in The Ashes, Martin Fone ponders the derivation of the Aussies nickname for

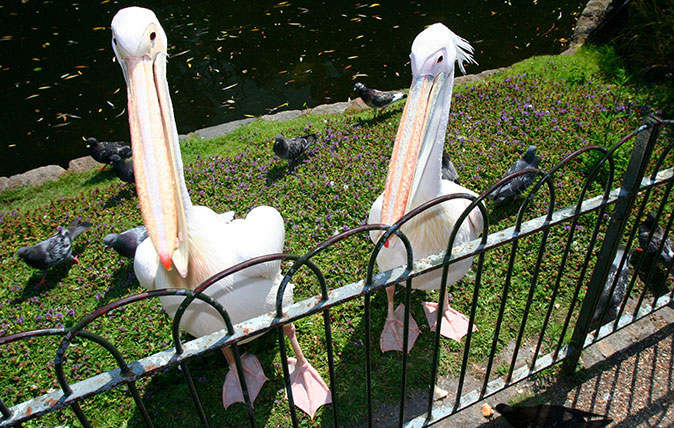

How the St James's Park pelicans sparked a Cold War stand-off between Russia and the USA

Former diplomat Alistair Kerr tells the strange tale of the pelicans that live in the centre of London – and how

Why do we all want to live in the countryside?

It's in our DNA.