At last, a new chapter for the Reading Room at the British Museum

The British Museum’s Reading Room — where Sylvia Pankhurst and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle once worked — has reopened at last. Richard MacKichan celebrates.

Opened by the late Queen in 2000, the Great Court of the British Museum quickly became an icon of the capital’s cultural landscape. If you’ve ever wondered what used to fill that gleaming space before it was a courtyard, well, it formed most of the British Library. From 1997, three storeys and several centuries’ worth of books were removed to their purpose-built St Pancras site, allowing Foster + Partners’ glass-covered creation to take shape. Some of that library, however, never left.

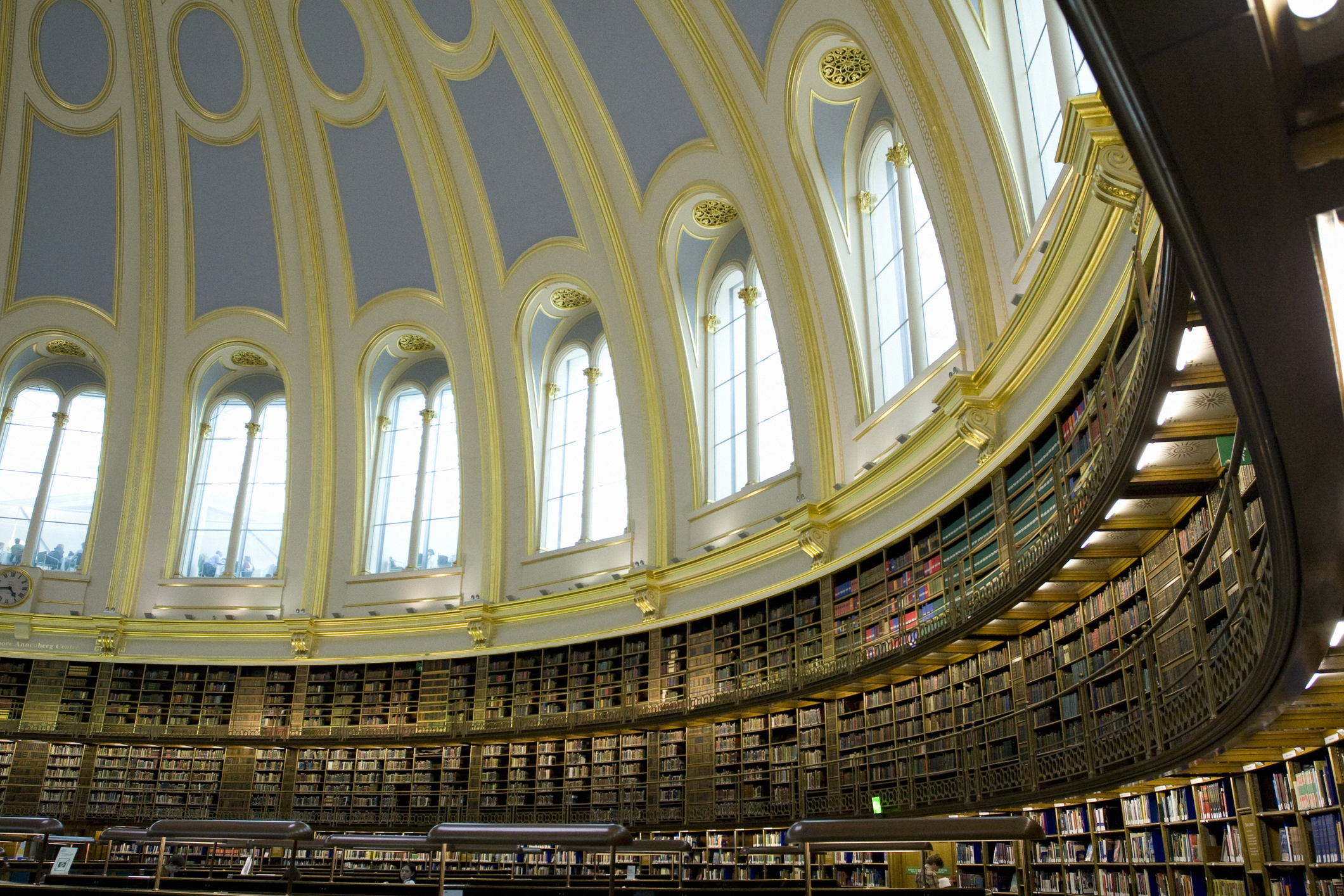

The cylindrical centrepiece to which all that tessellated glass is affixed is the original round Reading Room, which has spent much of its new life off limits. Until now.

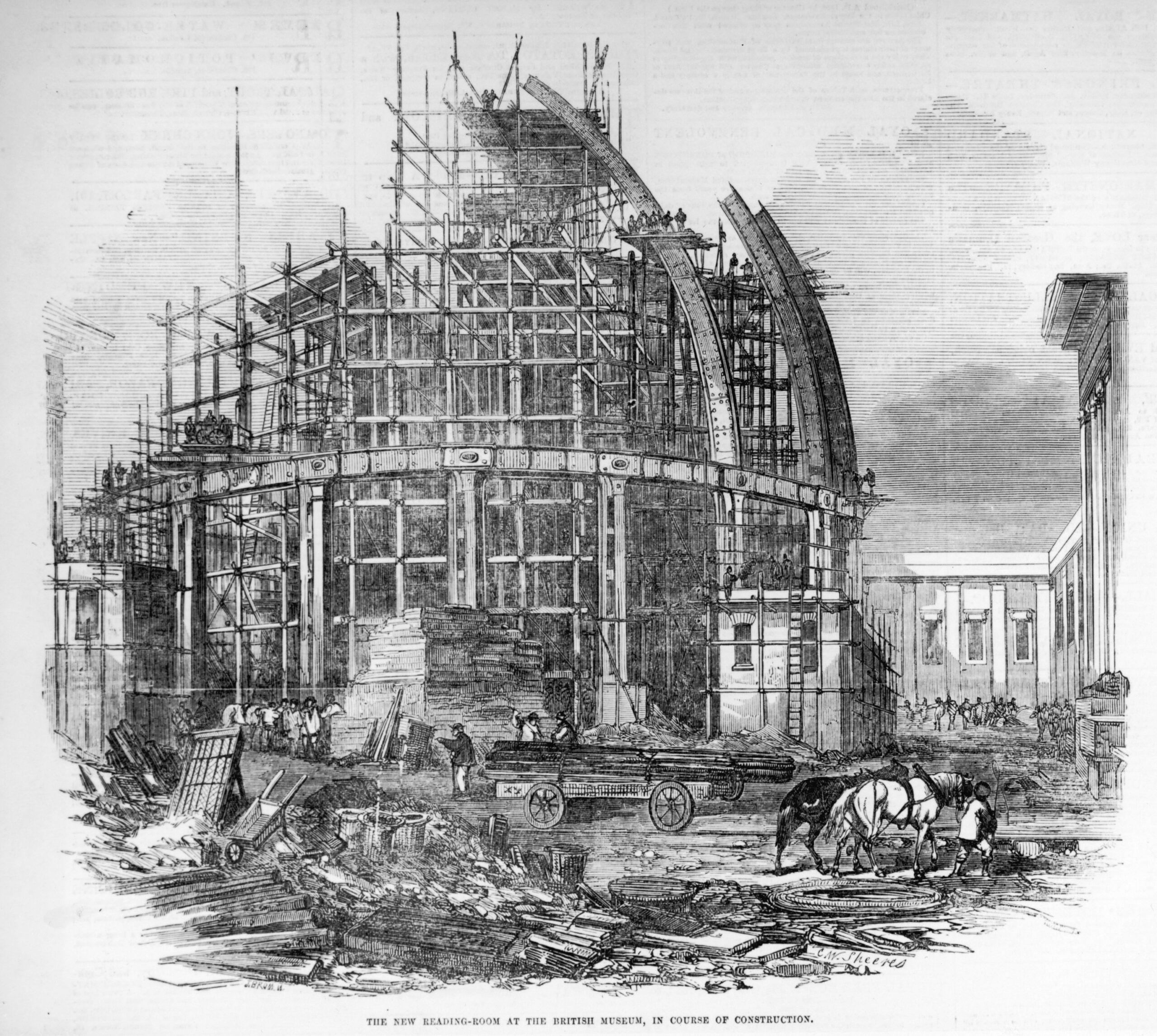

The domed Reading Room first opened on May 2, 1857, designed by architect Sydney Smirke (another of whose famous domes sits atop the Imperial War Museum), after principal librarian Antonio Panizzi suggested a round room would help with storage. More than 60,000 people visited in its first 10 days.

It had been open again for only a fortnight when I entered 167 years later, yet was already thronged with people, curious Londoners keen — thrilled, even — to see behind these long-closed doors.

The vast turn-of-the-millennium revamp saw the Reading Room become a visitor centre initially and, from 2007, it was the museum’s main temporary exhibition gallery, hosting, among other things, China’s Terracotta Army.

However, save for a few private tours, it’s been largely shuttered to the public since 2013 and clamour had been growing for its reopening. Former museum director Hartwig Fischer said in 2018 that the round Reading Room ‘needs to be an integral part of the museum’. The chairman, former chancellor George Osborne, said in 2022 that its closure was ‘not acceptable’.

As the sign on the left of the door now proclaims, the room is finally ‘as it was when it was freshly painted in 1857’, which can’t have been an easy task. The ceiling itself is papier mâché (bolstered by iron struts, lest you fear for its sturdiness), which required a delicate touch-up. Thankfully, the ‘peculiar’ smell of old leather and musty overcoats that was recorded in many dispatches from its 19th-century visitors lingers no longer.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

One downside of the room’s 1857 iteration was the light. Librarians and readers had to rely on natural light from the dome and a few gas lanterns, so London’s smog could rule out whole days. Twenty-two years later, it became one of the first buildings in the capital to have electric lighting installed.

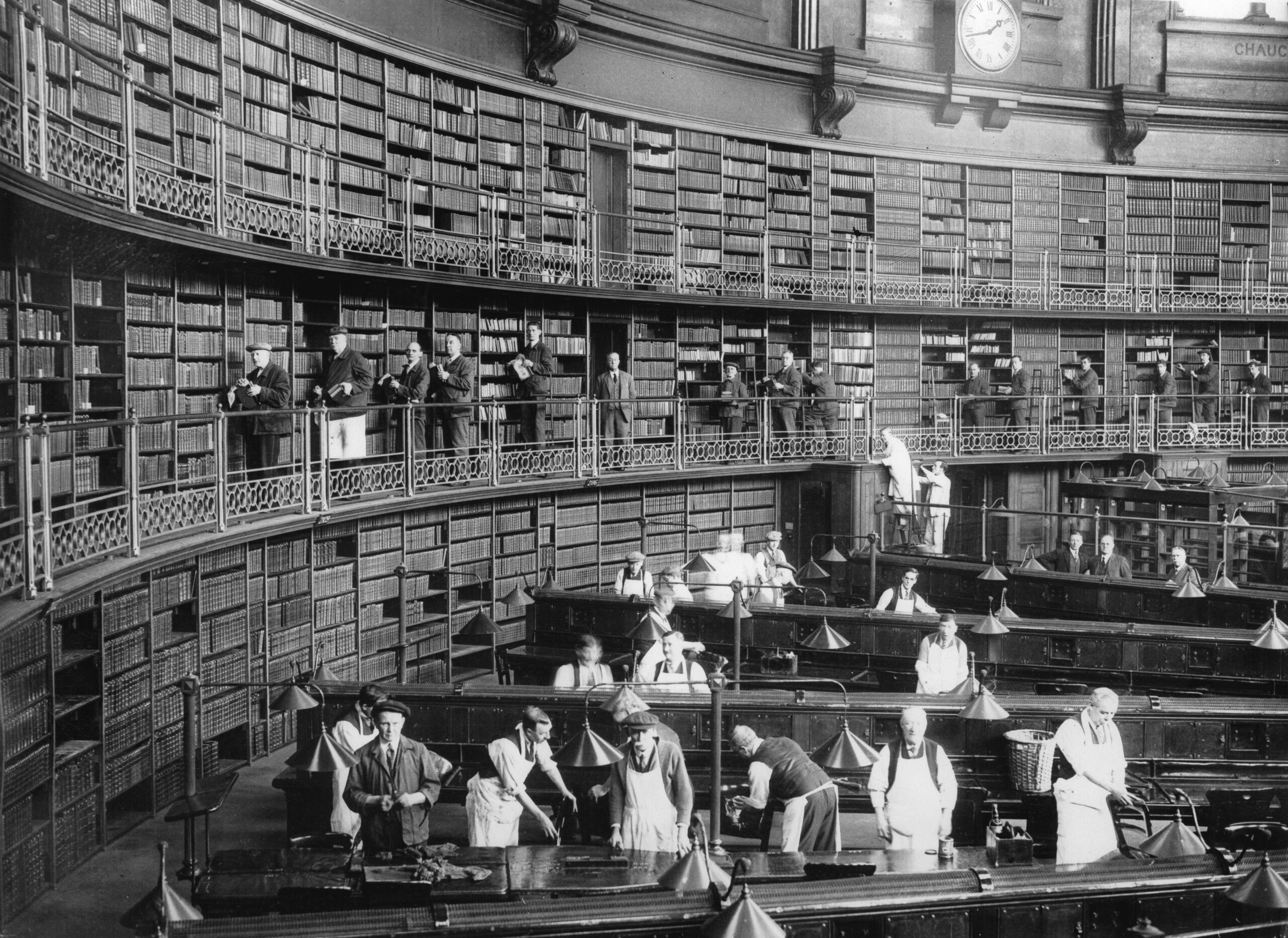

Visitors can’t sit and read in the namesake room’s new guise, but they can watch the archive team at work. Methods have hardly changed; books may still not be taken outside the Reading Room and it can take a while for the team to track down a single title among its three miles of bookcases and 25 miles of shelves.

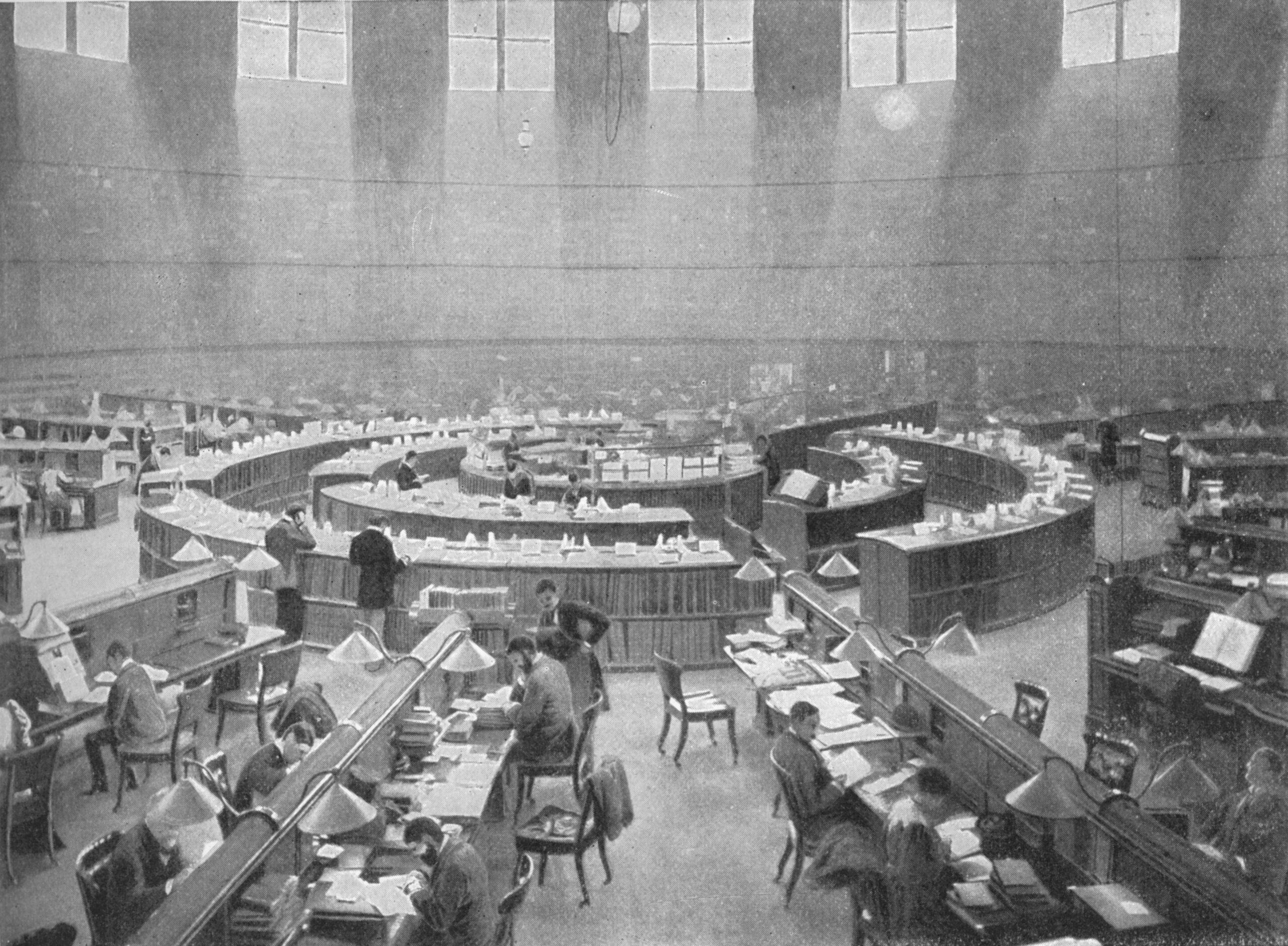

It must take some adjusting to having the public descend on their workplace, but the configuration of the viewing space means much less chance of the staff nodding off, a phenomenon mentioned in a few of the room’s new displays. A 1926 report in The Star recorded it thus: ‘Long tables radiate like the spokes of a spider’s web; and here sit hundreds of human flies… some digging hard in pursuit of knowledge and scratching their heads at the hard words; others curled up and sleeping like babes.’ Perhaps it was the underfloor heating?

Some of the room’s most notable visitors are highlighted, from ‘father of the Chinese nation’ Sun Yat-sen to Sylvia Pankhurst (who came to research women’s employment) and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (who made Sherlock Holmes a frequent Reading Room visitor). Granted, visitors will be more staring in wonder than researching in earnest, but it is splendid to have the jewel restored to the architectural crown of the British Museum at last.

Visit www.britishmuseum.org

The British Museum is at a nadir in its fortunes — it's a brave person stepping up to take charge

Our cultural columnist Athena on the challenges — the many challenges — for Nicholas Cullinan, the new director of the British Museum.

Credit: Stephen Millership

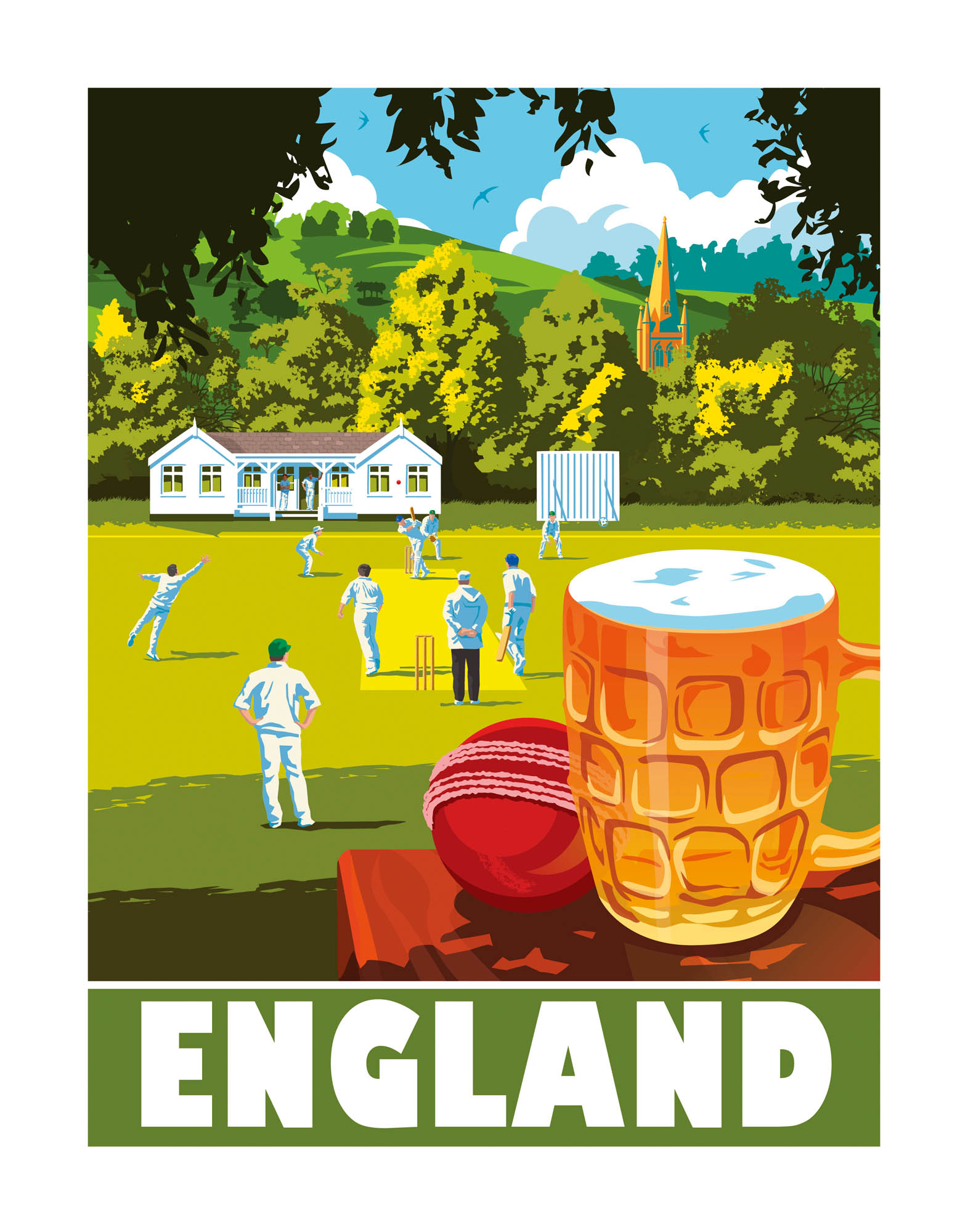

Stephen Millership: The man whose classic posters distill the spirit of the British countryside

From the mauve sky of Waterloo Sunset to the pastoral Arcadia of rolling fields in God’s Own Country, Stephen Millership’s

The strangest museum in London? Dennis Severs’ House is art installation, theatre set and 18th century throwback

Tactfully revived, Dennis Severs’ House defies categorisation, finds Jeremy Musson.

-

Seven of the UK’s best Arts and Crafts buildings — and you can stay in all of them

Seven of the UK’s best Arts and Crafts buildings — and you can stay in all of themThe Arts and Crafts movement was an international design trend with roots in the UK — and lots of buildings built and decorated in the style have since been turned into hotels.

By Ben West

-

A Grecian masterpiece that might be one of the nation's finest homes comes up for sale in Kent

A Grecian masterpiece that might be one of the nation's finest homes comes up for sale in KentGrade I-listed Holwood House sits in 40 acres of private parkland just 15 miles from central London. It is spectacular.

By Penny Churchill