Almshouses: What they are, how they were created and why they're still relevant in the 21st century

Built for the clergy, the military, retired estate workers and, most commonly, for the poor, almshouses are as important today as they ever were, finds Clive Aslet.

Only half an hour’s walk from Winchester, the Hospital of St Cross, founded in 1132, could be an Oxford or Cambridge college. It stands serene in its semi-rural Hampshire setting as part of the triumvirate of great medieval foundations in Winchester, together with the cathedral and Winchester College.

The purpose that it fulfils, however, is probably rather less well understood than that of the church or the public school. For the hospital, despite its name, is an almshouse, serving a more or less identical role to the one for which it was established eight centuries ago. It is one of about 2,000 across the country, all venerable, if rarely as old as St Cross. We might, however, wonder how they are faring in this age of social change.

They come in many forms, often having been founded to serve specific groups — the clergy, the military, the poor from particular places and the not so poor, who pay (as some people have always done) for the privilege of joining. All provide a place to which their residents may retire from the wider world, but still feel part of a community, perhaps formed by people who share a common background from their working lives. This is not the case, however, at St Cross, the master of which, the Revd Terry Hemming, is proud of the social diversity over which he presides. The brothers, as residents are called, include a former bulldozer driver, as well as a retired professor of botany. One brother is about to be 100, but recruiting newcomers has been difficult during the pandemic. With a capacity of 23, numbers are down to 18.

‘I think the hospital satisfies three needs that people feel in old age,’ explains Mr Hemming. ‘There’s the need for security, as it is hard to imagine anyone being thrown out once they’re accepted. Another need is community: the brothers attend a church service every day except, curiously, Sundays and eat lunch together. The grounds are big enough for them to avoid each other if they prefer, but there’s companionship for those who want it. Thirdly, some people need the delight of living amid beautiful surroundings.’

Only men are taken at St Cross — a tradition that reflects medieval practice, although it is of surprisingly recent date in its present iteration. Within living memory, St Cross used to take married couples, but reverted to its original, all-male condition because Winchester has a second almshouse, St John’s, which welcomes women.

The oldest British almshouse still in operation is another hospital — that of St Oswald in Worcester — founded in 990. Its name reflects the meaning of ‘hospital’ in the Middle Ages, not as somewhere to (possibly) cure the sick and wounded, but a place that received travellers and pilgrims, as well as housing the needy and infirm. Inmates might be blind, insane or leprous; very often, they were simply old and unable to fend for themselves. These charitable institutions served as retirement homes, perhaps for specific groups such as the clergy — although maintained priests would usually be housed in monasteries.

When Edward III founded the Order of the Garter and St George’s Chapel in 1348, he created a college for 26 alms knights or poor knights — a romantic gesture that perhaps reflected the straits of those who had been captured by the French and forced to sell their estates to raise ransoms after the Battle of Crécy. It survives as the Military Knights of Windsor — the members are retired army officers, with a uniform of scarlet tailcoat, sword, sash and cocked hat with plume — and which proudly boasts to be the oldest establishment in the British army. In towns, prosperous merchants provided alms or charitable relief for destitute members of their guilds. Poor inhabitants of almshouses might serve as bedesmen, tasked to say masses for the founder’s soul, to hasten its passage through Purgatory.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

However, not everyone in an almshouse was badly off. Royal servants who could no longer work or favourite soldiers who had lost a limb were sent to monasteries, hospitals and almshouses. Wealthy people who had no family to look after them could buy a corrody that provided for their support. More is known about them than poorer inhabitants, as their terms of entry were written down. At the Hospital of St Mary and St Cuthbert, at Greatham in Co Durham, Matthew Lardener had a private room, meals at the chaplain’s table, a servant, fodder for a horse and a gown, renewed every year, which was suitable for a squire. His daily portion consisted of two loaves, a flagon of the best ale and a mess of food from the kitchen.

Although Henri of Blois, grandson of William the Conqueror, founded the Hospital of St Cross for 13 poor brothers, who were given black robes to wear, it was enlarged in the 15th century by Cardinal Beaufort; the new intake, dressed in red, belonged to the Order of Noble Poverty. Within living memory, the Black Brothers were expected to fag for the Red Brothers — a system that has now been abolished.

As was the case with all great medieval buildings, almshouses usually had a great hall and a chapel, which were often attached. The plan of the accommodation depended on the scale of the foundation and the buildings that were already on site. The accommodation must have varied, but, as early as the 13th century, the Hospital of St Mary Magdalene at Glastonbury, Somerset, seems to have offered each of its 10 poor men his own room.

Throughout the Middle Ages, charity had been dispensed by or through the Church. Although the Hospital of St Cross survived Henry VIII’s reign, the Dissolution of the Monasteries destroyed the infrastructure of almsgiving. Some of the most splendid almshouses were built by the richest inhabitants of Tudor and Elizabethan England. Lord Leycester Hospital at Warwick, founded by Queen Elizabeth’s favourite Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, for wounded soldiers and their wives in 1571, was a refoundation of an ancient institution run by guilds. Its half-timbered buildings, with varied rooflines, are nothing less than rhapsodic.

The Hospital of St John Baptist without the Barrs at Lichfield, Staffordshire, is another ancient foundation, the principal frontage of which was rebuilt after the Dissolution with a row of eight brick chimneys — evidence of the comforts then provided, as the new rooms had the luxury of fireplaces. (The Barrs refer to the city gates.) Despite its name, Abbot’s Hospital at Guildford in Surrey was never monastic, having been founded by the Archbishop of Canterbury George Abbot as a gift ‘out of my love to the place of my birth’ in 1619; its formal name is the Hospital of the Blessed Trinity.

In 1611, Thomas Sutton, nicknamed Croesus by his contemporaries, left a legacy to establish a school and almshouse on the seven acres of the old Carthusian monastery — the Charterhouse — at Smithfield, just outside the City of London. Although the school left smoky London for the green fields of Surrey in 1872, the almshouse remains, providing a home to 40 old men and (since 2018) women. They live as a community, able to go out whenever they like, but eating meals in the 15th-century great hall if they wish to. Unlike many almshouses, the Charterhouse can care for those brothers who can no longer look after themselves in its own infirmary.

London also boasts the Royal Hospital Chelsea, established as England’s answer to Les Invalides in Paris, with buildings designed by Sir Christopher Wren and a famous uniform of scarlet frock coat and tricorn hat. In 1802, what are now called the Friendly Almshouses were founded to help ‘aged and poor women of good character residing within 10 miles of St Paul’s Cathedral’.

Many of today’s almshouses date from the Victorian period, when they were an object of philanthropy for Yorkshire mill owners such as Sir Titus Salt and Richard Crossley. The reforming spirit of the times reinvigorated old foundations, but not before the Revd Francis North — son of the Bishop of Winchester, who became the Master of the Hospital of St Cross in 1808 — had pocketed an estimated £300,000 of the hospital’s income during his 40 years in post. An inquiry ordered restitution, yet North, not having resigned until 1855, only repaid about £4,000. The scandal inspired Anthony Trollope with the plot of The Warden.

For the past 21 years, St Cross has been home to the man of letters and John Betjeman biographer Bevis Hillier, who joined as a relative stripling at the age of 60. ‘My mother had recently died and I knew St Cross from having visited at the age of 20,’ he explains. ‘I thought, even then, that it was somewhere I would like to live one day.’

The admissions process involved — as it still does — an interview with the master, followed by two nights at the hospital, to assess whether the applicant would fit in. Once accepted, the new arrival spends six months as a postulant, before being admitted as a full brother. ‘I loved being at Oxford, living in medieval buildings,’ discloses Brother Bevis. ‘The other day, I was looking at the great row of chimneys at St Cross and thinking how lucky I was to live in such harmonious surroundings. My rooms date from 1445 and there is a graffito that one of the brothers carved in 1512.’

Time past and time present, as T. S. Eliot might have said, are both contained in the future of Britain’s flourishing almshouses.

Give, if thou can, an alms

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the Almshouses Association, which represents 1,600 of the some 2,000 almshouses still in the country. Today, 36,000 people live in almshouses, pursuing full and independent lives. The majority are of retirement age, of limited financial means and have lived for some time within the vicinity of an almshouse charity or have a family connection with the area.

Most almshouses are managed by a team of volunteers, occasionally under a warden or manager. Residents pay a weekly maintenance contribution. Recently, 57 new almshouses have been built in Bermondsey, London SE16, testament to their continued relevance.

For more information, telephone 01344 452922 or visit www.almshouses.org

Ten masterpieces of twentieth century architecture at risk from the wrecking ball

The Twentieth Century Society's annual list of at-risk buildings has been released, and — as ever — will stimulate lively

The architecture of the National Gallery, 'one of the defining landmarks of London'

In the wake of the re-opening of museums, John Goodall looks at the architecture of the National Gallery in London

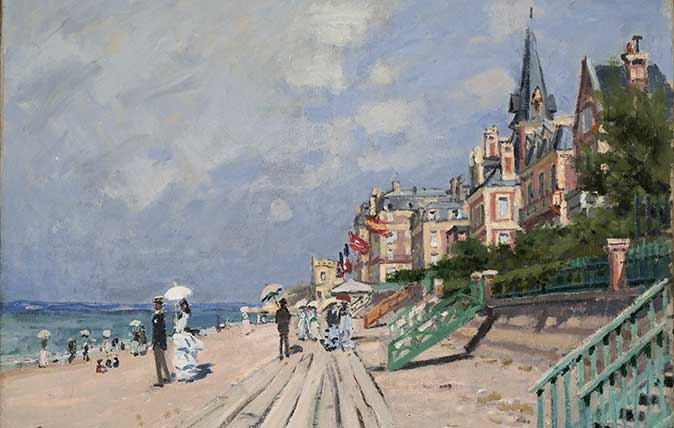

In Focus: The paintings which show Monet's genius for architecture as well as nature

Think of Monet and you think of reflections and nature, but his works included huge amounts of architecture and other