Alexander 'Greek' Thomson: Glasgow's visionary architect

As we celebrate the bicentenary of Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson, Gavin Stamp considers the remarkable way in which he adapted principles of Greek architecture to the development of his native city.

In 1874, the year before his death, in a public lecture on Greek architecture, Alexander Thomson (1817-1875) asked his Glasgow audience ‘to turn and look for a moment at the Acropolis of Athens, as it appeared when Greece was the light of the world’. He described its ‘beautiful forms composed of marble of pearly whiteness, and the azure, crimson and gold with which they were partially tinted’. This, he suggested, was ‘one of the most glorious sights which the human eye has ever been permitted to behold and the like of which it will never again see in this world’.

Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson never saw the Acropolis and never went to Greece. In fact, he never crossed the Channel and almost all his work was confined to the west of Scotland. ‘Greek’ Thomson he may have been, but he was not one of the conventional, archaeological Greek Revivalists; indeed, as far as he was concerned, they ‘failed to master their style, and so became its slaves’.

Thomson’s physical insularity stimulated a fertile and inventive imagination and he dreamed of the ancient world, applying the architectural principles he discerned in the monuments of Egypt, Greece and the Near East to the modern buildings he designed for Victorian Glasgow.

In this smoky, polluted industrial city on the Clyde, Thomson managed to design, with rare brilliance and ingenuity, warehouses and commercial offices, blocks of tenements and terraces of houses, suburban villas and three great temples for the United Presbyterian Church.

Today, his achievement is generally seen to be of less importance - certainly, less fashionable - than the work of his fellow Glaswegian C. R. Mackintosh (whose 150th birthday will be celebrated with rather greater fanfare next year). However, in the words of the architect Mark Baines, his work ‘seems to be of continuing relevance in any pursuit of an urban architecture, for there is a sensibility exhibited in buildings that is able to confer an equal dignity upon all sections of society without unnecessary distinction’.

Largely self-educated, Thomson was in the best traditions of the Scottish Enlightenment. A devout Presbyterian, a thinker and a dreamer, evidently inspired by the apocalyptic, visionary images of the painter John Martin, he was nevertheless a highly practical architect. Thomson was happy to experiment with new materials, such as structural cast-iron and large windows of plate glass, and designed not only buildings, but also ironwork and terracotta chimney pots, furniture and interior decoration.

The continuing fascination of his work lies partly in an inquiring mind applying to modern conditions the architectural principles he held to, the God-given ‘eternal laws’ he understood in Ancient Egypt and Greece: ‘We do not contrive rules; we discover laws. There is such a thing as architectural truth.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

These laws governed his approach to domestic architecture, inside and out. As Thomas Gildard, his admirer and memorialist, put it in 1888: ‘With Mr Thomson, the designing of a building did not cease with the plasterwork and joinery. It extended to the coloured decoration and this was as original, beautiful and characteristic as were the groupings or the mouldings.’

Thomson began his career designing villas down the Firth of Clyde in a variety of fashionable styles: Italianate, Baronial, even Gothic, a style he argued was inherently unstable and later turned violently against (‘Stonehenge is really more scientifically constructed than York Minster’). And then, in the middle of the 1850s, he seems to have decided that just one style, the trabeated Greek, must henceforth be the vehicle for his endeavours.

As Sir John Summerson once wrote, with Thomson, ‘the Greek Revival had turned itself into a new style, still mostly Greek but also romantically abstract’. And the modern, personal Greek style that he developed can be seen as a bridge between the villas of Schinkel in Germany and the early prairie houses of Frank Lloyd Wright.

After the villas came terraces of houses for Glasgow. These are remarkable compositions in which he strove for architectural unity. Thomson did not invent the building type, of course, but, whereas the terraces in, say, Bloomsbury or Bath sometimes tried to appear as single grand palace fronts, Thomson’s were novel compositions, each unique, in which the houses were combined in different ways.

The grandest was Great Western Terrace, in which he combined two- and three-storey houses in an unprecedented arrangement, full of optical subtleties. ‘Only a genius of a high order could, with so few, and seemingly so simple, elements design a building of such composed unity,’ wrote Thomas Gildard. ‘The windows have no dressings, but Greek goddesses could afford to appear undressed.’

Unity was often achieved by having doors and windows equally spaced and of equal width, rising to the same height. This is the case with his first terrace, Moray Place in Strathbungo, with the unifying first-floor colonnade of 52 square piers, exemplifying Thomson’s belief that ‘all who have studied works of art must have been struck by the mysterious power of the horizontal element in carrying the mind away into space and into speculations on infinity’.

For him, windows were a problem that gave rise to ingenious solutions. He wished them to appear only as voids between structural elements - whether walls or piers - so he used the largest sheets of glass he could find, with few glazing bars and a minimal frame. Sometimes, he placed his windows like a curtain wall behind and detached from the structural piers and sometimes hanging his sashes so they could descend as well as rise (and making careful provision for fixing blinds or curtains).

Thomson also lavished care on his domestic interiors. His ceiling plasterwork, with rosettes placed on wide, flat surrounds, is distinctive. His joinery is unique: doorframes could be like small Stonehenge megaliths, with an overhanging lintel. The doors themselves were given a single, central pier below a transom—a form derived ultimately from the engraving of the (lost) Choragic Monument of Thrasyllus in Stuart’s and Revett’s Antiquities of Athens.

His ironwork, including balustrades and balcony fronts, creatively adapts Greek patterns cast at Walter Macfarlane’s Saracen Foundry. Then, there is colour. By the 1840s, it was widely known that Greek temples were originally brightly coloured and this may have informed Thomson’s predilection for covering internal walls in polychromatic patterns derived from Greek motifs. In some of his early schemes, he is said to have cut his own stencils; later, he worked with professional decorators.

Inside, the Queen’s Park Church, his lost (bombed) masterpiece, the spectacular decoration was carried out by the artist Daniel Cottier. ‘I want nothing better than the religion that produced art like that,’ exclaimed Ford Madox Brown when he saw it. ‘Here, line and colouring are suggestive of Paradise itself.’

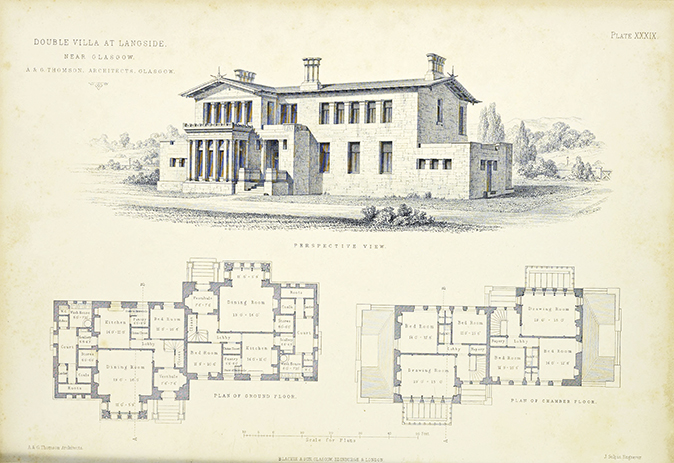

Thomson’s principles may be studied in his two most celebrated houses. The first is Maria Villa in Langside, to the south of Glasgow. Built in 1856–57, it is, today, better known as the Double Villa because it is, in fact, a pair of semi-detached houses. It does not look like it, however, because, instead of duplicating the plan of one house as a mirror image, Thomson turned it through 180° so that each side of the building presents an identical, but asymmetrically composed elevation.

Each, therefore, is something that was, in fact, novel, a Grecian villa conceived in Picturesque terms: before Thomson, Italianate or Gothic villas could be asymmetrical, but Grecian ones were designed with axial symmetry.

Maria Villa presents a brilliant composition in what was now the austere Thomson style, an affair of continuous wall planes, square structural piers and low-pitched roofs (not, perhaps, ideal in the climate of the west of Scotland).

One of these houses has been carefully restored internally and presents rooms entirely panelled in timber in a distinctive, perhaps eccentric manner, articulated by thin projecting pilaster strips. The design of the Double Villa was published by Blackie & Son in 1868 in a book entitled Villa and Cottage Architecture, in which the accompanying texts were presumably supplied by the architect.

In this case, he wrote: ‘The whole of the interior finishings are of carefully selected yellow pine, the enrichments being frets of mahogany planted upon it. The wood is varnished, preserving its natural colour and markings, no stain of any kind being used. The effect of this mode of treatment is to unite together the several parts of the room, thereby giving an effect of increased extent.’

Thomson’s finest and most elaborate villa, Holmwood House, was built in 1857–8. It was commissioned by James Couper, a paper manufacturer, and it may have been intended as a showcase for his products as well as for entertaining. Gildard marvelled: ‘If architecture be poetry in stone and lime - a great temple an epic - this exquisite little gem, at once classic and picturesque, is as complete, self-contained and polished as a sonnet.’

The key, again, to understanding the originality of this ‘adaptation of the Greek’ is its combination of the Classical and the Picturesque.

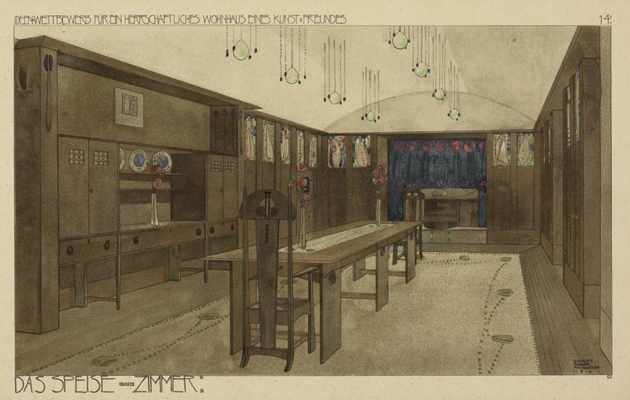

In its cleverly asymmetrical composition, extended horizontally by a long wall, each large room is clearly expressed externally. The bay window of the parlour appears as if it is a circular Ionic temple and, at the other end of the villa, three huge windows (with sashes that go both up and down) announce the tall, single-storey dining room.

This room incorporates a frieze based on John Flaxman’s illustrations of Homer’s Iliad. At the far end is a toplit recess that contained a sideboard ‘of white marble’, according to Villa and Cottage Architecture, ‘with enrichments incised and gilt; and the back and ends of the recess have mirrors in mahogany framing, decorated with rosewood frets’.

This has now been re-created as part of the exemplary ongoing restoration of the interiors at Holmwood being carried out by the National Trust for Scotland, guardians of this masterpiece since it was saved by The Alexander Thomson Society from probable destruction.

The first floor is reached by a staircase under a strange exotic lantern, rising from darkness into light. As always in Thomson’s houses, the drawing room is on this upper level. Here, the walls were once adorned with panels painted by Hugh Cameron depicting Tennyson’s Idylls of the King (long since removed). What survives are the white marble chimneypiece with incised ornament and the decorative ceiling.

Thomson’s (downstairs) dining rooms usually had a stylised sunburst in the centre of the plaster ceiling and, in his drawing rooms, the ceiling represented the night sky, with plaster stars. Here, at Holmwood, yet more stars were painted on the dark-blue plaster between the raised gilded stars, as if to suggest even more remote constellations.

In that lecture he gave in 1874, Thomson speculated about ‘the inhabitants of the distant spheres’ and about space travel as well as about the motives of his Creator. He mused about the speed of light and how there were stars so distant that their light had not yet reached us, so that, ‘if it were possible for us to fly off into space, we might, as we retire, survey backwards, as it were, all the events that have happened on our planet - that we might, by going to a sufficient distance, witness the very first act of its creation’.

Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson was not only a great and original architect, he was also a dreamer, almost a mystic.

Exhibition review: Mackintosh Architecture at RIBA, London

Gavin Stamp explores a show of Charles Rennie Mackintosh designs.

Gothic for the Steam Age: An illustrated biography of George Gilbert Scott by Gavin Stamp

John Goodall is impressed by this concise and beautifully illustrated account of Scott's achievements.

A doll's house fit for a queen: How Lutyens created a Lilliput for Queen Mary

A miniature palace designed by Lutyens and promoted by Country Life offers a fascinating perspective on the 1920s, as Gavin

-

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera season

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera seasonBy Annunciata Elwes

-

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'A party barn is the ultimate good-time utopia, devoid of the toil of a home gym or the practicalities of a home office. Modern efforts are a world away from the draughty, hay-bales-and-a-hi-fi set-up of yesteryear.

By Annabel Dixon

-

High Wardington House: A warm, characterful home that shows just what can be achieved with thought, invention and humour

High Wardington House: A warm, characterful home that shows just what can be achieved with thought, invention and humourAt High Wardington House in Oxfordshire — the home of Mr and Mrs Norman Hudson — a pre-eminent country house adviser has created a home from a 300-year-old farmhouse and farmyard. Jeremy Musson explains; photography by Will Pryce for Country Life.

By Jeremy Musson

-

Sir Edwin Lutyens and the architecture of the biggest bank in the world

Sir Edwin Lutyens and the architecture of the biggest bank in the worldSir Edwin Lutyens became the de facto architect of one of Britain's biggest financial institutions, Midland Bank — then the biggest bank in the world, and now part of the HSBC. Clive Aslet looks at how it came about through his connection with Reginald McKenna.

By Clive Aslet

-

'There are architects and architects, but only one ARCHITECT': Sir Edwin Lutyens and the wartime Chancellor who helped launch his stellar career

'There are architects and architects, but only one ARCHITECT': Sir Edwin Lutyens and the wartime Chancellor who helped launch his stellar careerClive Aslet explores the relationship between Sir Edwin Lutyens and perhaps his most important private client, the politician and financier Reginald McKenna.

By Clive Aslet

-

Cath Harries — The photographer on a 15-year quest to find the most incredible doors in London

Cath Harries — The photographer on a 15-year quest to find the most incredible doors in LondonBy Toby Keel

-

The extraordinary Egyptian-style Leeds landmark hoping to become a second British Library — and they used to let sheep graze on the roof

The extraordinary Egyptian-style Leeds landmark hoping to become a second British Library — and they used to let sheep graze on the roofThe project has been awarded £10million from the Government, but will cost £70million in total.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

Art, architecture and plastic bricks at Lego House: 'It's as if the National Gallery set up easels and paints next to the masterpieces and invited you try your hand at creating a Van Gogh'

Art, architecture and plastic bricks at Lego House: 'It's as if the National Gallery set up easels and paints next to the masterpieces and invited you try your hand at creating a Van Gogh'The rural Danish town where Lego was created is dominated by the iconic toy — and at Lego House, it has a fittingly joyful site of pilgrimage. Toby Keel paid a visit.

By Toby Keel

-

Restoration House: The house in the heart of historic Rochester that housed Charles II and inspired Charles Dickens

Restoration House: The house in the heart of historic Rochester that housed Charles II and inspired Charles DickensJohn Goodall looks at Restoration House in Rochester, Kent — home of Robert Tucker and Jonathan Wilmot — and tells the tale of its remarkable salvation.

By John Goodall

-

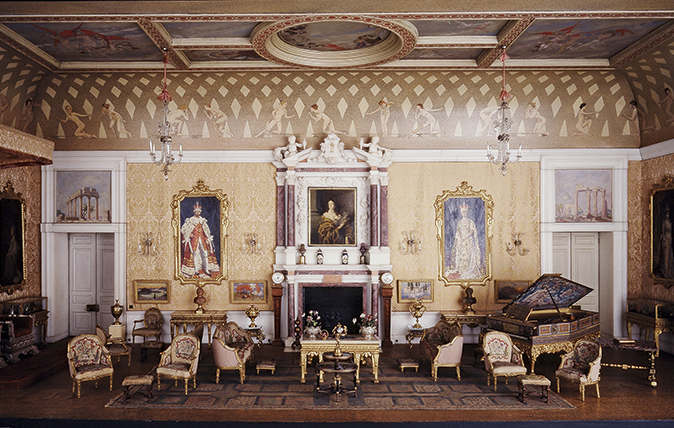

'A glimpse of the sublime': Inside the drawing room of the 'grandest Palladian house in Ireland'

'A glimpse of the sublime': Inside the drawing room of the 'grandest Palladian house in Ireland'The redecoration of the drawing room at Russborough House in Co Wicklow, Ireland, offers a fascinating insight into the aesthetic preoccupations of Grand Tourism in the mid 18th century. John Goodall explains; photography by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

By John Goodall