From abbot to artist: The remarkable journey of Abbots Grange, Worcestershire

A house built for the Abbot of Pershore in the 14th century was restored as a studio by an American artist and later became a family home. Alan Calder describes the development of this remarkable Cotswolds building. Photographs by Paul Highnam.

Tucked away behind high yew hedges in the very heart of the village of Broadway in the north Cotswolds is a building that predates the picturesque 17th-century houses on the celebrated High Street by nearly three centuries. Erected in about 1330, this is not only an exceptionally important example of medieval domestic architecture, but the most complete house of its date built for the private use of an abbot outside his monastery in England. Restored and enlarged in stages from the 1880s onwards, the house has subsequently undergone changes that exemplify the inventive, but sympathetic spirit of the Arts-and-Crafts Movement.

'The heads of religious houses, especially, started living on these manors, building houses that were commensurate with their wealth'

The Benedictine Abbey of Pershore claimed possession of the manor of Broadway from at least the 10th century, their ownership confirmed by royal charter in 972. A manor house must have existed there from the Anglo-Saxon period, but the present Abbots Grange is a much later building that came into being as the result of a change in the organisation of the abbey’s estates during the 12th and 13th centuries.

In this period, rather than manage their assets in common, many Benedictine monasteries began to assign manors in their possession to particular officers termed Obedientaries – such as cellarer, sacristan or abbot – who would use the revenues to discharge their duties. An unintended consequence of this was that the beneficiaries of these arrangements enjoyed unprecedented independence from their communities. The heads of religious houses, especially, started living on these manors, building houses that were commensurate with their wealth.

Broadway passed into the possession of the Abbot of Pershore in the early 13th century as part of this redistribution of the community’s monastic endowment. In 1251, moreover, the abbots were granted ‘free warren’ here by the king. This royal licence to hunt expressed lordship and might also imply that the property had become a place of retreat and relaxation.

It’s not clear from the documentary record who built Abbots Grange, although to judge from the technical details of the architecture – such as the window tracery patterns, mouldings and the use of double-curve arches termed ogees – the whole was constructed at one time and probably dates to about 1330. In the early 14th century, it was a mark of exceptional expense to construct a domestic building in stone (rather than with a timber frame). This fact, not to mention the quality of the workmanship, underlines the relative ambition of the Grange.

This is a surprise because the community of Pershore was pleading extreme poverty in the first half of the 14th century. Evidently, the abbot must have built the house using his own independent resources. The most plausible patron, as identified by Edward Impey, is Abbot William de Herwynton.

He was elected in 1307 and resigned from office in 1340. Perhaps he retired here.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The house created by the abbot is unusually well-preserved, although heavily restored. At its heart was the hall, a tall interior originally heated by an open fire and covered by an open roof of two bays. The great timber braces that divide the roof formerly sprang from shafts of stone, a rare detail. Set mid way down the room, the shafts and braces probably demarcated the extent of the dais area for the abbot’s table in the more prestigious ‘high’ end of the room.

The corresponding ‘low’ end was arranged with facing entrance doors. Next to these in the north gable wall are three doors leading to the kitchen, buttery and pantry. The free-standing kitchen building may be shown in a drawing of about 1820 by Edward Blore (British Library, Add. MSS 42018, f. 15). In the later Middle Ages, it was common to screen off the entrance and service doors from the body of the hall. The Broadway building predates the period when such arrangements became conventional and, therefore, originally lacked such a screen.

To the south of the hall is a two-storey cross wing that probably comprised a parlour below and a bedchamber with a fireplace above. From the latter, there was access to a small projecting chapel. The undercroft of the chapel opens off the high end of the hall and may have been used as a domestic space to retreat from the hall.

This house continued in the possession of Pershore’s abbots without material change until 1538, when it was seized by the Crown. Over the next few centuries, the building was owned by a number of private individuals and internally adapted. During the 1800s, it was used as the parish workhouse and for housing prisoners awaiting their appearance before the Justices at Worcester. Later still, it was adapted as three cottages.

As the fabric deteriorated, the future of the building hung in the balance, until the antiquarian and romantic rediscovery of Broadway in the late 19th century.

The house was described to the British Archaeological Association in 1875 and, in 1881, The Builder published a full survey of the fabric. According to the accompanying article, the then owner, a Mr Halliwell-Phillipps, who had recently purchased the building, was so impressed by its archaeological importance that he proposed to abandon his plans (drawn up by architect John Robinson) to restore it as a residence and, instead, ‘render it safe from the effects of time and weather, for the investigation and study of all those lovers of antiquity who may desire to visit it’.

'Alarmed at reports that he intended to turn it into a house, the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings wrote to him, urging caution'

The interest in Broadway continued to grow, however. Among those charmed by the village was a circle of rich Americans, who saw it as an unspoilt rural idyll with vernacular buildings of great quality and individuality. Some passed through, staying in The Lygon Arms, which was redeveloped as a hotel of international repute. Others settled, such as the charismatic American Shakespearian stage actress Mary Anderson de Navarro, the glittering chatelaine of fin-de-siecle Broadway society. She bought Court Farm in the Upper High Street in 1894, where she played host to European royalty, prime ministers and her illustrious friends G. F. Watts, Henry James, J. M. Barrie, Lord Tennyson and Edward Elgar.

Another figure in this circle was the American artist Frank Millet, who moved into the village in 1885. He lived initially at Farnham House and then Russell House, but gained access to Abbots Grange to use as his studio. In her autobiography A Few More Memories (1936), de Navarro described her visits to the Grange, where she would witness Millet, John Sargent, Edwin Abbey, Lawrence Alma-Tadema and Alfred Parsons working on their paintings.

The atmospheric medieval interior of the building provided a backdrop for Millet’s historical paintings, including perhaps his most famous picture, Between Two Fires, vividly described by de Navarro as ‘the Puritan with pious hands and devilish eyes between two serving wenches’.

By 1892, Millet had purchased the property and set to work on its repair. Alarmed at reports that he intended to turn it into a house, the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) wrote to him, urging caution. The letter was misdirected, however, and his reply – preserved in the SPAB archives – dated more than two years later, September 10, 1894, explained that he had only undertaken essential repairs and had no intention of living in the building. He went on to assure SPAB that the grandee architect Sir Arthur Blomfield had approved his plans.

When a member from the society visited a year later, on October 13, 1895, he was shown around a building site: the roof of the hall had been removed, its internal partitions dismantled (revealing lots of architectural fragments that were subsequently reused in the building) and most of the plaster from the interior stripped off.

It was, the visitor regretfully reported, a ‘restoration’ and that he had arrived too late to do much good. Millet, who evidently directed the project, raced round the site speaking with such enthusiasm and animation that it was difficult to ‘get a word in edgeways’; he had worked with such pains to re-create the original form of the building that he believed himself ‘absolutely infallible’. He is described as having recorded all the details of the project in a diary.

In 1907, more than a decade later, Millet appointed the London-based Glaswegian Andrew Prentice (1866–1941) as his architect to extend the building. The Scotsman came on the recommendation of de Navarro, who had employed him at Court Farm.

He had also adapted nearby Orchard Farm for Lady Maud Bowes-Lyon and would subsequently design a large new house in the village called Luggershill (1911), for Alfred Parsons, and Lifford Memorial Hall (1915).

'The largest of the two new gables is pierced with a striking 24-light mullioned and transomed window that floods illumination into the painter’s studio'

Prentice designed a substantial new double-height studio wing at the northern end of Abbots Grange. It is deferentially set back from the line of the medieval hall, with gables composed to echo those of the old building. The largest of the two new gables is pierced with a striking 24-light mullioned and transomed window that floods illumination into the painter’s studio.

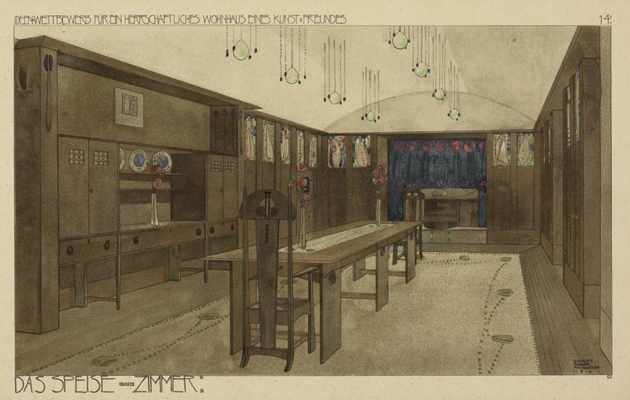

The restored house was featured in Country Life (January 14, 1911) and the architect’s original watercolour drawings of his design are preserved in the archives of the Worcestershire Archive Service.

Millet perished on RMS Titanic in 1912. He was last seen helping women and children into the lifeboats. Afterwards, his family and his many friends in Broadway had a handsome new lych-gate to the church of St Eadburgha erected in his memory.

Following his death, his widow, Lily, commissioned Prentice to subdivide her late husband’s double-height studio, creating a drawing room, now a dining room, and bedroom on the ground floor with two bedrooms above. Prentice had also designed an extension at the south-west corner of the house, comprising a single storey with scullery, pantry and stores. This extension was expanded to create a two-storey wing, including a kitchen with bedrooms above.

Twenty years later, in 1933, the versatile and talented Birmingham architect Charles Bateman (1863–1947) was commissioned to carry out further work at Abbots Grange. Bateman was admired for his clever and well-crafted Cotswold work, his flagship project being the restoration of The Lygon Arms. He also worked on a number of other historic properties in the village, as well as the substantial 17th-century houses of Tower Close (Country Life, July 16, 2014) and Green Close in the nearby village of Snowshill.

His brief at Abbots Grange was to design a two-storey entrance wing on the west side of the property, which was to provide a porch, hall and bedroom above. Bateman respectfully followed the materials, massing and design vocabulary of the existing building, but his front-gable treatment was innovative and imaginative.

He designed an open porch approached through a stone colonnade with square-end columns and two muscular central circular columns. Above the entrance, the bedroom was illuminated by a canted oriel window with a sweeping stone slate roof in the 17th-century Cotswold tradition. The bedroom was given the trademark Bateman feature of a barrel-vaulted ceiling.

For the past 20 years, the building has been owned by the Taee family, whose Cotswolds-based craft bakery and tea rooms business Huffkins supplies most of the royal palaces, as well as high-end retailers around the world. The Taees fell in love with the property, appreciating its historical and architectural importance as one of the country’s best preserved medieval, domestic monastic buildings.

Abbots Grange is the family home, but parts of it are offered as exclusive accommodation for visitors to Broadway. Here, in the centre of one of the most picturesque villages in the Cotswolds, guests can experience the ambience and atmosphere of a remarkable and rare medieval building.

For further information, visit www.abbotsgrange.com.

Acknowledgements: Edward Impey and Matthew Slocombe

Wells Cathedral, Somerset: A symphony of architecture

In the first of two articles, John Goodall describes the architectural development of Wells and the struggle of its late-medieval

Credit: ©Paul Highnam/Country Life Picture Library

Country Life's best architecture stories of 2018: Destruction, salvation and the Gunpowder Plot

Our roster of architecture writers have brought some astonishing stories of country houses which have survived and now thrive despite

Exhibition review: Mackintosh Architecture at RIBA, London

Gavin Stamp explores a show of Charles Rennie Mackintosh designs.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

London's Tate Modern celebrates its 25th birthday with the help of a giant arachnid and crustaceous telephone

London's Tate Modern celebrates its 25th birthday with the help of a giant arachnid and crustaceous telephoneArtwork by Louise Bourgeois and Salvador Dali, among others, will be on display for the gallery's Birthday Weekender event.

-

'The watch is Head Boy of men’s accessorising': Ginnie Chadwyck-Healey and Tom Chamberlin's Summer Season style secrets

'The watch is Head Boy of men’s accessorising': Ginnie Chadwyck-Healey and Tom Chamberlin's Summer Season style secretsWhen it comes to dressing for the Season, accessories will transform an outfit. Ginnie Chadwyck-Healey and Tom Chamberlin, both stylish summer-party veterans, offer some sage advice.