How Beeleigh Abbey became the much-loved home of one of Britain's great bookshop owners

In the second of two articles, David Robinson looks at Beeleigh’s chequered history in the centuries after the Dissolution, culminating with ownership by the Foyle family of the eponymous bookshop.

William Foyle (1885−1963), co-founder of Foyles, the celebrated bookshop on Charing Cross Road in London, enjoyed sailing on the tidal rivers of Essex. One day, in the early 1940s, messing about in a boat on the Chelmer, he is supposed to have happened upon Beeleigh Abbey (read the story of its creation here). Immediately captivated, Foyle was determined to live there, regardless of his wife’s initial despair. He approached the owner, Richard Thomas, who agreed to sell him the estate in 1943. Foyles still live at the abbey today.

Of course, for the origins of Beeleigh as a secular residence, we must look back much further, all the way to the 16th century. In 1536, as the suppression of the medieval abbey (the subject of last week’s article) began to look inevitable, Beeleigh was soon recognised as a potential asset. The hereditary founder, Henry Bourchier, 2nd Earl of Essex, was quick to show his hand. He was prepared to pay the Crown 1,000 marks (£666) for a grant of the site, promising that ‘it shall never be used as a religious house again’.

In spite of his family ties to Beeleigh, however, the Earl’s pursuit of the property fell on deaf ears. Instead, in 1537, it was leased to the Essex-born John Gates (d. 1553), an ambitious courtier who was known to both Henry VIII and Thomas Cromwell. By 1540, Gates was in a position to pay the sum of £300 to acquire the core of the former abbey estate outright. The grant included ‘the house and site of the late monastery… the church, steeple, and churchyard, and divers pastures’, together with various properties in the surrounding neighbourhood.

The specific fate of the abbey buildings, not only in the time of Gates, but on into the late 16th and 17th centuries, is entirely undocumented. It’s clear, nevertheless, that the early Tudor secularisation of Beeleigh mirrored a pattern found in the immediate afterlife of many of the country’s now-defunct medieval religious houses. Hundreds, in fact, were transformed — like Beeleigh — into comfortable domestic residences, of varying architectural scale and form.

Based on events elsewhere, it seems likely that Gates witnessed a degree of calculated Crown destruction at Beeleigh. At least, soon after the departure of the abbey community, the church roofs would have been removed, windows smashed and every ounce of valuable lead set aside for the King’s use. Gates himself may well have sanctioned further demolition. Even so, the east range of cloister buildings was quite deliberately retained, seemingly always with residential use in mind.

Given his definite preference for houses elsewhere, it seems doubtful that Gates ever envisaged living at Beeleigh himself. Indeed, his primary objective could well have been short-term gain. To this end, almost immediately after acquiring the lease in 1537, he appears to have sublet the property to Thomas Mapell, a yeoman of Chipping Ongar. Then, less than a decade later, in September 1546, Gates was granted licence to sell Beeleigh to a William Marche of Calais (d. 1549).

From Marche’s son, the estate passed to Thomas Franck (d. 1558), whose principal seat was at Ryse in the parish of Hatfield Broad Oak. Although his grandson, Richard (d. 1627), apparently contemplated a sale in 1593, some four generations of the family were to retain Beeleigh through to the 1630s. It is notable, however, that in all this time, the Francks showed very little interest in modernising the principal architectural spaces of their property to any significant degree.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

This said, we should certainly not overlook the timber-frame extension at the southern end of the house (Fig 3). Tree-ring dating now indicates that this was built in about 1624, only a few years before Richard Franck’s death. Structurally, it is of three storeys and incorporates a dense — and, therefore, expensive — timber frame. On the show side, overlooking the principal entrance to the house, it was enhanced with jettied (projecting) upper floors and attractive brick nogging, set largely in herringbone fashion.

Clearly, by the early 17th century, someone had decided that Beeleigh required warmer and more intimate living accommodation, presumably including further bedrooms (Fig 2), set apart from the large abbey chambers. Whether this was the Francks themselves is doubtful; a wealthy gentry family would be more likely to adapt the building in a more ambitious manner. The work is possibly more in keeping with the aspirations of a fairly well-to-do tenant family.

In fact, this same pattern of absentee landlords, most of whom we can trace, and tenants who remain anonymous, continues all the way through to the mid 19th century. Thus, in 1632, Richard Franck’s sons sold Beeleigh to a Thomas Craythorne and, some two decades later, it was acquired in turn by a London merchant, Robert Ingram. In 1698, Ingram’s son sold it for £1,700 to yet another London merchant, one John Bludworth (d. 1699), whose family held it into the early 1730s.

It was during the Bludworth period of ownership, probably in about 1710−20, that Beeleigh was visited by the antiquarian William Stukeley, who produced a sketch plan and several drawings of the house. Stukeley’s ‘East Prospect’, is especially interesting. It confirms that there was a second storey over the projecting bay of the medieval chapterhouse, an unusual arrangement that perhaps allowed for a muniment room above the ground-floor vault.

A further succession of absentee landlords held Beeleigh throughout the 18th century, until, in 1801, it was settled on Frances Shuttleworth at the time of her marriage to the surgeon, Benjamin Baker. The Bakers, initially of Maldon Hall, held the estate for the next 120 years. The house itself, meanwhile, continued to be occupied by tenants.

According to several early-19th-century accounts, the former abbey chapterhouse was then in use ‘as a hogsty’ (Fig 4), whereas the canons’ day room appears to have served largely as a farmhouse kitchen. From the 1841 and 1851 census returns, we finally learn the name of a Beeleigh tenant: Thomas Keys, described as a market gardener. He and his family appear to have shared the property with a George Hicks, an agricultural labourer. When the Revd Frederick Spurrell visited the site in 1864, he wrote of ‘a luxuriant market garden’ on the east side of the house and noted that the chapterhouse ‘at present… makes a good dairy’.

It’s somewhat remarkable, then, that, in much the same era, we can trace growing scholarly interest in the significance of the medieval abbey. Apart from Spurrell, for instance, the quality of Beeleigh’s architecture was brought to much wider attention through a set of superb measured drawings that were produced by the architect James Hadfield and published in 1848.

All the while, however, as we can see from a number of late-19th- and early-20th-century photographs and drawings, much of the external fabric had gradually been deteriorating. In particular, the entire floor over the chapterhouse vault had evidently collapsed, or had been deliberately removed, to be replaced by no more than a lean-to roof.

From about 1891, Beeleigh was occupied by John Doyle Field, a retired engineer, who seems to have begun restoring the property. Following his death, in 1912 a lease was granted to Capt Frederick W. Grantham. He was sufficiently enthralled by Beeleigh to engage the architect, Basil Ionides (1884–1950), to make substantial improvements to the property. The programme included rebuilding the floor above the chapterhouse and the addition of further living accommodation projecting into the south-east corner of the former cloister. Sadly, Grantham himself did not live long enough to enjoy his modernisations. He was killed on the Western Front in May 1915.

In 1920, Beeleigh and its immediate estate were finally sold by Samuel Sidney Baker to Jessie Harriette, the wife of Richard Thomas. Together, the couple continued the work of restoration on the property. It was Thomas, as we noted last week, who produced a scholarly volume on the abbey, with chapters by the noted historian R. C. Fowler and the architectural historian Alfred Clapham. In turn, this led to the Country Life account by Christopher Hussey of 1922.

It was the same Richard Thomas who, in 1943, agreed to sell Beeleigh to William Foyle (Fig 5a). They came to an arrangement whereby Thomas was allowed to live at the abbey as a tenant until he was ready to move, which he did in 1945. That same year, Foyle stepped down as head of his bookshop and took up residence at Beeleigh with his wife, Christina.

A generous and hospitable host, Foyle lived life to the full. His love of the abbey and its history is reflected in the small guidebook he produced under the Foyle imprint in 1950. He also commissioned the sculptor, Frederick Brook Hitch, to produce a statue of the abbey’s founder, Robert Mantell, which was erected on the lawn east of the house in the very year he and Christina had moved in.

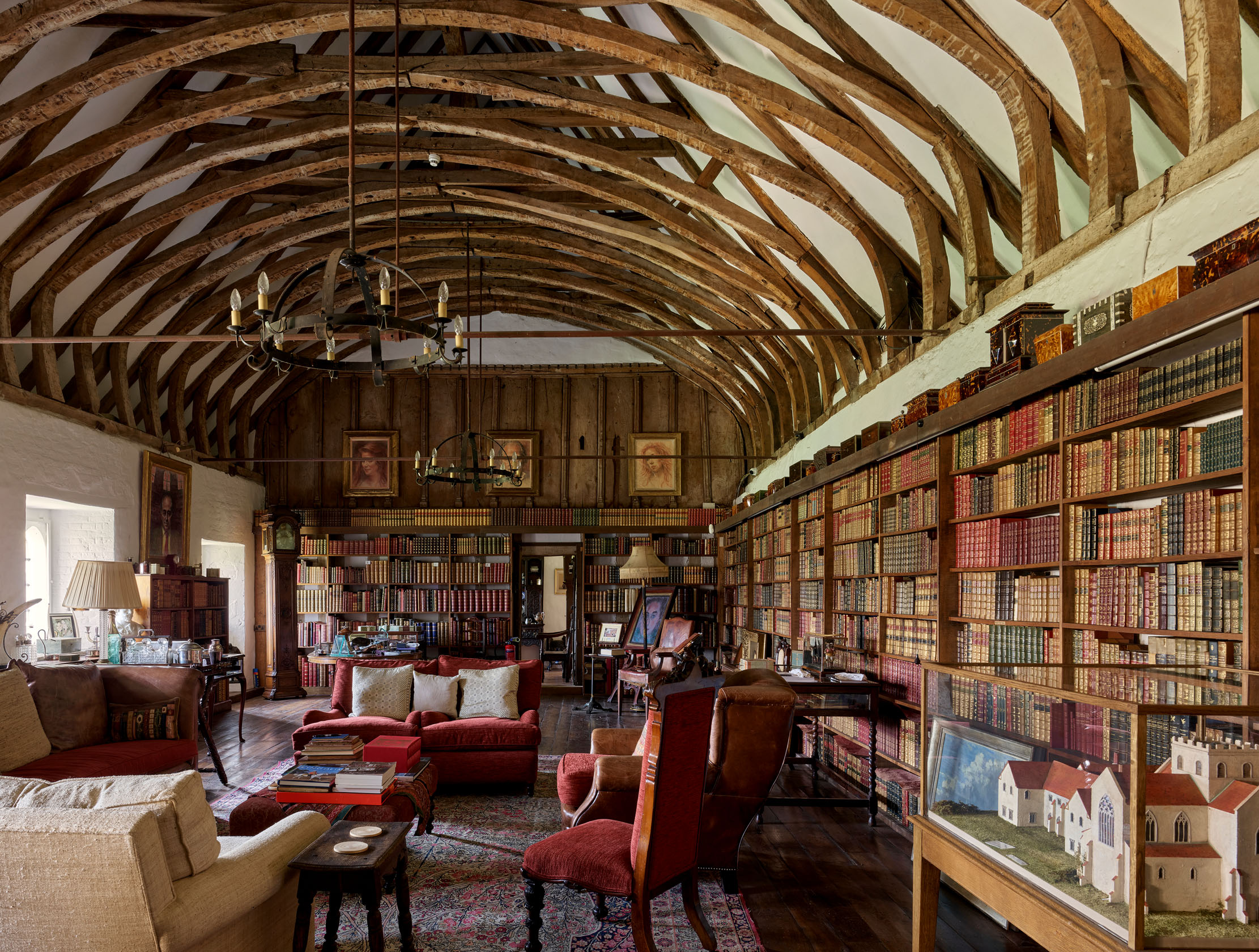

As one of the Country Life pictures of 1922 reveals, Thomas had used the former canons’ dormitory as his library. Foyle was to follow suit, but on an altogether grander scale (Fig 1). He had already developed a considerable interest in rare books, but now began to indulge his passion with even greater enthusiasm (Fig 6). At the time of his death in 1963, the library housed more than 4,000 books and manuscripts, ranging from the 11th to the 20th century. In paying tribute to Foyle’s talent as a collector, the auction house Christie’s described it as ‘one of the largest private libraries of the 20th century’.

When Christina died in 1976, the estate passed to the couple’s second daughter, also Christina (Fig 5b), who lived at Beeleigh with her husband, Ronald Batty.

Famously eccentric and autocratic (Fig 7), other than her success with the celebrated Foyles Literary Luncheons, Christina pushed the bookshop ever closer to extinction. On her death in 1999, her entire wealth was consigned to a charity, now known as the Foyle Foundation. The bulk of the Beeleigh library had to be sold, the auction realising a total of £12.6 million, a ‘new record price for a European private library’.

The house itself, together with most of its contents and many of the books, were bought by one of William’s grandsons, Christopher Foyle, together with his wife, Catherine. The couple immediately embarked on a major programme of essential conservation and sympathetic modernisation, with the quality of the work recognised in several awards. Their transformation of Beeleigh has also included significant, and ongoing, improvements to the splendid gardens under gardener Chris Cork.

Christopher, meanwhile, had been brought back into the family business by his aunt, Christina. He served as chairman of Foyles until the firm was sold to Waterstones in 2018. Sadly, Christopher died in August of this year. Generous and affable, he clearly had a deep love for the abbey, extending all the way back to regular boyhood visits to stay with his grandfather. In their own contribution to Beeleigh’s architecture and ongoing history, Christopher and Catherine Foyle have secured the future of the house.

Beeleigh Abbey: An incredible medieval house that's barely altered since Henry VIII's Dissolution of the monasteries

David Robinson looks at Beeleigh Abbey — the Essex home of Catherine and the late Christopher Foyle — an exceptional