Simon Jenkins: Europe's cathedrals are the true wonders of the world, and were once daubed in colour — it's time they were once more

Our cathedrals were once filled with colour, argues Simon Jenkins, and today's monochrome restorations are a historical travesty.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Imagine a visit to the National Gallery in which every picture you see is black and white. The faces, the landscapes, even the dramas are all clear. They are simply devoid of colour. Fine, you might say, but something is missing. That is how I react to a medieval cathedral.

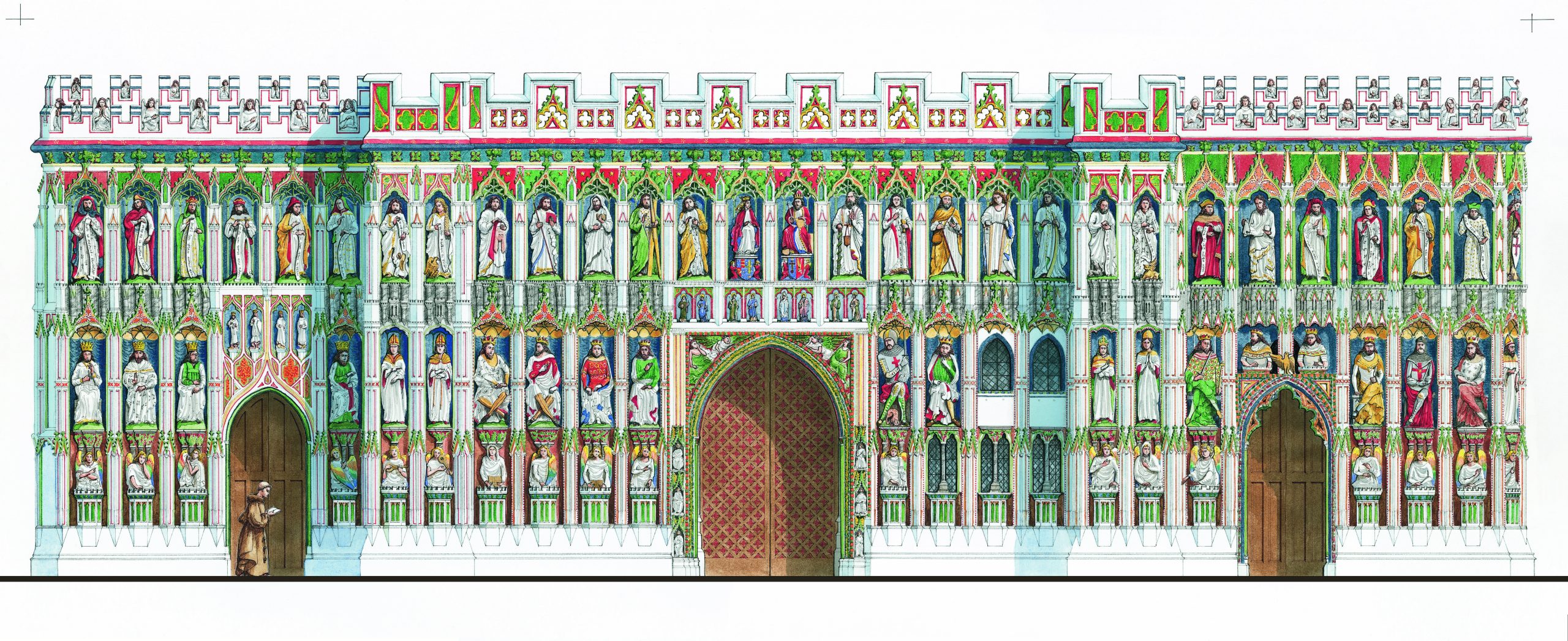

Mostly, they are colourless. The vibrancy in which their creators bathed them has been stripped away by time and fashion. Gone are the visual textures intended to lift the eyes of worshippers and pilgrims from their drab surroundings, dazzling them with a polychrome Heaven. In their place, all we get is a dull, mostly limestone buff.

As displays of the culture of Europe in the Middle Ages, nothing compares with the great cathedrals. They are true wonders of the world. They tower over the Continent, from mighty Durham to serene Chartres, from Cologne’s battling buttresses to Seville’s exquisite vault, the last ordered to be so vast ‘that men will think us mad’. Nowhere equalled the reckless engineering of Beauvais. Lincoln in its prime was taller than the great pyramid of Cheops. Yet few of these buildings appear as they did to those who made them because all have lost their colour.

Colour in piers, ribs and murals naturally faded with the decline of Catholic supremacy from the 16th century onwards. For worshippers, churches were no longer the exclusive illustrators of the Bible story.

It is hard for us to imagine how coloured west fronts and interiors must have looked to those who never saw painted images anywhere else in their lives. As it was, iconoclasm, neglect and whitewash did their worst.

Statues crumbled and were not re-carved. Only in Italy did decoration widely survive, thanks largely to marble and the robustness of mosaic, as in St Mark’s, Venice, and Palermo’s Monreale. Even colour embedded in stained glass was discarded. Salisbury’s was found dumped in a ditch. The light of day should be Heaven enough, colour was vulgar and certainly un-Protestant.

When the 19th century turned its attention to restoration, colour did return to murals and statues, but rarely to architecture. The polychrome stonework of William Butterfield and J. L. Pearson was not widely imitated, although George Gilbert Scott did paint much of his woodwork. Pugin’s neo-Gothic Catholic churches were far closer to their medieval precursors. The nearest 20th-century England came to a serious revival of colour was the historian Ernest Tristram’s inter-war work. He studied medieval paint chemistry and found sponsors in Exeter and Bristol cathedrals, but had an unhappy habit of waxing paintings. Conservation purists put a stop to such licence.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The post-war doctrine of ‘conserve as found’ laid a dead hand on cathedral archaeology. No risk may be taken, no sign of antique revivalism permitted. With a few exceptions — curiously, including roof bosses — paint in a church may be ‘stabilised’, but not reapplied. Where murals survive, they do so as meaningless blurs staring from whitened walls. Medieval statues on the west fronts of Wells and Exeter — which in France would have been replaced — are left in eroded meaninglessness.

Likewise, the great Neville screen in Durham stands as a panel of niches devoid of statues. Church screens everywhere look like an art gallery from which paintings have been taken, leaving only their frames. Some committee once declared that Classical tombs could be restored and painted, but not Gothic ones, so Gothic always appears grim and ascetic, compared with the colourful Renaissance. This is historic travesty. British conservation remains trapped in an ideology of barrenness.

Certainly, we cannot tell how extensive, or how vivid, were the colours used in adorning a medieval cathedral. We can only dig into the stone. Yet when video illumination re-creates these colours, the shock of distaste can be considerable. It recalls the dismay that greeted the revelation that Robert Adam’s fashionably pastel 18th-century shades were originally garishly bright.

The Middle Ages, likewise, were nothing if not garish. The recent retouching of the 12th-century Portico de la Gloria at Santiago de Compostela in Spain merely hints at the blast of colour that must have welcomed pilgrims to this medieval masterpiece. The V&A Museum’s replica cast of the portico has dared not replicate the paint.

Europe’s great cathedrals are almost all restored. The work has been magnificent. As places of worship, they are remarkably popular, in contrast with the decline in parish worship. They are emerging not only as majestic works of art, but as leading civic and cultural institutions. Yet many still bear little resemblance to what their medieval admirers might recognise. Essentially, they express the ascetic taste of the 18th and 19th centuries, the age of architectural monochrome.

There do exist a few glimpses of what a new age of authentic cathedral restoration might offer, a new truthfulness to their past. Apart from Tristram’s Bristol and Exeter Lady Chapels and Pugin’s neo-Gothic Cheadle in Staffordshire, a more substantial example is the east end of Normandy’s Coutances cathedral, its ribs and piers offering a fair- ground of colourful delights. Limited if vivid insertions are the statuary screens in Ripon and St Albans cathedrals.

A little-known effort in the same direction is the relocation of Swansea’s St Teilo’s church to a site in Wales’s St Fagans Museum. Here, with scrupulous scholarship, the museum has restored the church as it would have been in the early 16th century, down to the smallest detail in murals, painted roof, rood screen and carvings. It well displays the ‘fairground’ atmosphere of pre-Reformation Christianity. Medieval need not mean dark, bleak and tumbledown.

St Teilo’s should form a template for restored medieval churches everywhere. Redundancy now threatens literally hundreds of them across Britain and Europe. Returning to them some sense of their ancient vitality and sense of fun must hold the key to reintegrating them into the secular life of their communities — much as they were in the Middle Ages.

A vicarious glimpse of how cathedrals might once have looked is offered in their nocturnal illumination by lighting technology. In 2016 and 2018, French artist Patrice Warrener ‘painted’ with coloured lasers the statuary on the west front of Westminster Abbey. It was phenomenal, picking out the flesh tones of faces and the shades of individual costumes. Few had even noticed there were statues on the façade. It was little short of a ‘new’ Westminster.

The son et lumière specialists Chroma stage a similar annual light show on the west front of Amiens in France, the most sensational display of architectural illumination I have ever seen. The show ends with every detail of the 14th-century façade lit in all its original glory. Then someone throws a switch and renders it all black. A similar impact is created, this time using refracted daylight and stained glass, in what is surely Europe’s most breathtaking Gothic interior, Antoni Gaudí’s Sagrada Familia, Barcelona.

These artists and architects are displaying the medieval cathedral as their creators intended. They are anthems to colour. We should pick up the challenge and hear the medieval masons cheering.

Simon Jenkins’s ‘Europe’s 100 Best Cathedrals’ is published by Penguin at £30

The 100 greatest cathedrals in Europe, as picked by Simon Jenkins

Simon Jenkins gives himself a daunting task with his latest book, Europe's 100 Best Cathedrals (Viking, £30), which does no

Simon Jenkins is a journalist and author who began his career at Country Life before going on to serve as the political editor of The Economist and editor of The Times.