The Channel Tunnel's centuries-long shift from fear of 'foreign hordes' who'd 'deface the countryside' to our magnificent link to the Continent

This week's architecture archive looks at the two centuries' worth of plans which eventually resulted in the Channel Tunnel between Britain and France.

Our regular look through the archives of Country Life in search of fascinating, architecture-related titbits usually turns up ancient marvels. This week, however, we’re looking at a more modern creation: the Channel Tunnel.

The reason for this is a chance moment in which we came across a fascinating leader article from September 20th, 1973 discussing the approval of the project, backed at the time by both French and British governments.

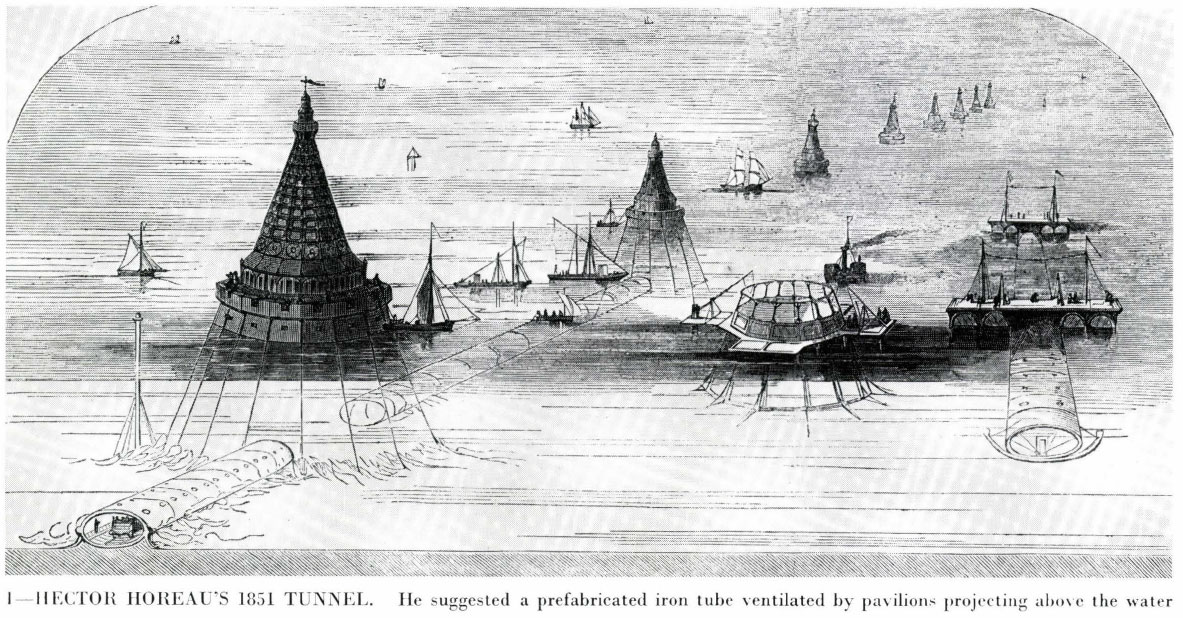

It’s now over two centuries since the idea of tunnel beneath the English Channel was first seriously suggested by a Napoleonic architect named Albert Mathieu-Favier. Little came of it back then, but as technology leapt ahead it prompted talks and exploratory digging throughout the 19th and 20th centuries before the tunnel eventually came to fruition. Digging began in 1988 and the first trains ran through the tunnel in 1994.

The reason it didn’t come earlier wasn’t so much down to will as to the opposition, as noted in a 1929 article in Popular Mechanics magazine, which discussed the opposition of military leaders to a tunnel which could theoretically facilitate an invasion. That wasn’t the only concern, however:

‘Not all of the objections raised against the plan from from the general staff. The doctrine of England’s “splendid isolation” was cited in some quarters, and the fear expressed that quick and comfortable train journeys would make England a holiday resort for hordes of more or less undesirable people, who would introduce foreign customs, deface the countryside and otherwise interrupt English habits of living.'

We’ll leave that quite stunning paragraph to speak for itself and fast forward 44 years later to give you Country Life’s take on the project after its approval:

After 170 years of intermittent discussion, the Channel Tunnel has, at last, received the Government's blessing, and is to go forward for Parliamentary approval. The details of the project remain, broadly speaking, as described in an article published in Country Life on June 21.

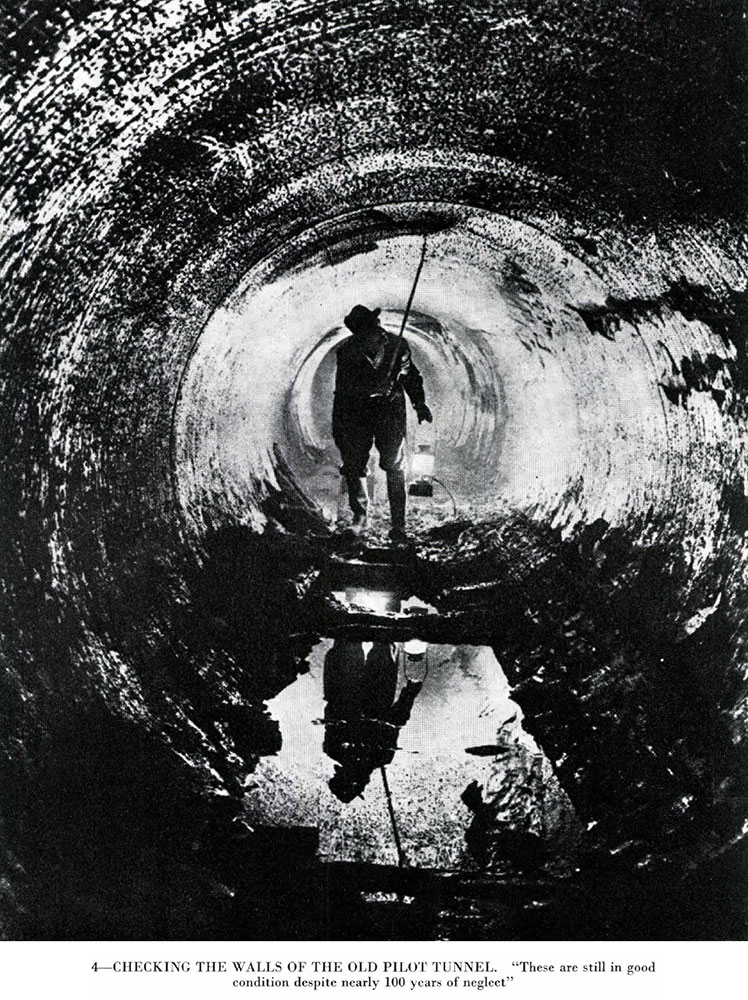

The article in question referred back to several previous plans over the years, including one effort begun from the 1860s which saw pilot tunnels being built — and as you can see we've reproduced some of its illustrations on this page.

But the 1973 plan is in essence what eventually went ahead in the 1980s: two separate rail tunnels, one running in each direction, with a third, smaller maintenance tunnel between the two.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

It seems sensible enough to have this link with the Continent, although emotional reasons probably play quite a large part in the objection to it. On the environmental question it is obvious, despite the undoubtedly sincere efforts of the Tunnel company over landscaping, that the terminal at Cheriton will completely change the character of the area.However, the land to the south of the site has already been built upon, and the terminal site itself is likely to be covered with houses during the next 20 years. It is, in fact, the logical place for Folkestone to expand; and, given the present growth in population, it must expand.Other arguments against the Tunnel include the fear that the road from London to Folkestone will carry a continuous procession of juggernauts; that it will draw road traffic from the Midlands, increasing the pressure through or round London; and that it will attract industry to Kent. Against this it can be said that the increase in ferry traffic would, to a large extent, have the same effect on the roads in any case, and at least the Tunnel will syphon off a lot of the traffic which would otherwise go through Folkestone or Dover. If the rail links are fully developed, they will take much of the container traffic, and prevent the overloading of the road to the coast.The growth of industry in Kent will not be as easily dealt with. Promises of strict planning controls made in 1973 may not carry much weight with a new generation in 20 years' time, who will see the Tunnel in operation and recognise the advantages of planting factories instead of hops on Kentish farmland.No doubt the debate will continue. The British and French governments have the option to cancel the project at any time, provided they pay the costs incurred . But with these running at over £800 million by 1980, second thoughts are going to be expensive.

As it turned out, that is exactly what happened: the newly-elected Labour government pulled the plug in 1975, amid fears that costs would double thanks to the the economic, political and social upheavals of the 1970s — not to mention the uncertainty over Britain's continued membership of the EEC. Plus ça change...

The truth of the matter is that there are so many unanswerable questions about the future of transport and economic growth that no one can predict the effect of the Tunnel, which is precisely why we have been dithering over it for so long.Life would certainly go on without the Tunnel. Who can say whether or not it will be better with it?

The cancellation was a major blow after a decade of work, but the project was resurrected and final approval came in 1986. It's hard not to see parallels with the recent approval of HS2. Who can indeed say whether or not we'll be better off thanks to large-scale engineering projects? The tunnel was a huge success, so much so that today's discussions are about a new tunnel, or even a bridge, linking Britain to the Continent. We'd love to know what the naysayers referred to by Popular Mechanics would have to say about that.

The Channel Tunnel: A quarter of a century old, over 200 years in the making

On the Channel Tunnel’s 25th birthday, Adam Jacot de Boinod applauds an extraordinary feat of engineering that was developed for

Credit: Alamy

What will HS2 do to house prices? Lessons from our recent history on what might happen, and when

Britain's new high-speed rail network linking the north and the south has been approved, in all its hugely-controversial, £100 billion-glory.

Jason Goodwin: 'They were more like beautiful professors of Hegelian dialectic than actual dogs'

Toby Keel is Country Life's Digital Director, and has been running the website and social media channels since 2016. A former sports journalist, he writes about property, cars, lifestyle, travel, nature.

-

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attached

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attachedUpper House in Derbyshire shows why the Kinder landscape was worth fighting for.

By James Fisher

-

John Sutcliffe — The man, the myth and the paint-naming legend behind Dead Salmon and Elephant's Breath

John Sutcliffe — The man, the myth and the paint-naming legend behind Dead Salmon and Elephant's BreathBy Carla Passino