Simon Lester goes out on a limb to identify species and stop us barking up the wrong tree.

Whether it’s a majestic oak or a wind-pruned thorn hanging on to life on an exposed coastline or a desolate moor, Britain’s trees are a truly remarkable and defining feature of our landscape.

Solemn, stately and statuesque, they have towered over our countryside for some 400 million years, offering breathtaking beauty, shelter, shade, fuel, food and the most versatile building material known to man. They are living documents of our very existence, which bring reassurance and hope through their indefatigable ability to outlive us.

Here’s our simple guide to identifying British trees.

Common lime – Tilia x europaea

Probably the tallest broad-leaved tree in Britain, the common lime is set apart from other limes by bushy side shoots that start from near the ground. Often seen in streets and parkland, this galleon of a tree is a true joy to sit beneath in July, when its sweetly scented flowers attract gently buzzing bees.

As well as feasting on the nectar and pollen, insects love to drink the honeydew deposited by aphids on the tree’s delicate, heart-shaped leaves, which have tiny tufts of white hair in the vein axils.

English oak – Quercus robur

Also called pedunculate oak, because it bears fruit or acorns on long stalks or ‘peduncles’, this is the most common oak in Britain. Set apart by its generous trunk, sturdy, crooked branches and expansive crown, the female flowers bloom on upright stalks, with the male equivalent appearing as hanging catkins.

Acorns develop, usually in pairs, next to alternate and distinctively scalloped stalkless leaves that have ear-like lobes at the base.

London plane – Platanus x hispanica

Brought here from Spain in the 17th century and planted for its ability to thrive in urban conditions (thanks to its bark, which sheds in large flakes, preventing the tree from becoming suffocated under sulphurous grime), the London plane is a hybrid of the Oriental plane and the American plane.

Its large, bright-green serrated leaves are up to 6in or more across, set alternately on the stem and not in opposite pairs. Ball-shaped male and female flowers flourish on the same tree, albeit on different stems. Once pollinated by the wind, the female flowers develop into bristly fruits.

Common beech – Fagus sylvatica

The mature beech—which can reach 130ft and develop a massive, many-branched dome—is a sight to behold, especially when it comes into bright-green leaf in May.

The mature beech—which can reach 130ft and develop a massive, many-branched dome—is a sight to behold, especially when it comes into bright-green leaf in May.

The dense canopy means only shade- tolerant plants can survive. However, this is made up for by the way splendid stands of these trees set the countryside ablaze in autumn, when their leaves turn orange, then rich red-brown. Both male (tassel-like) catkins and female flowers grow (in pairs, encased by a cup) on the same tree, which, once pollinated by the wind, houses beech mast.

Scots pine – Pinus sylvestris

Scotland was once covered by ancient Caledonian pine forest, but, now, only about 50,000 acres of these Tolkein-esque trees remain in the Highlands. Capable of reaching 115ft and living for 700 years, the trees’ scaly, warm-orange bark fissures with age.

Evergreen needles, which are shorter than those of other pines and have a blue tinge, are slightly twisted and grow in pairs on side shoots. Yellow male flowers appear at the base of these shoots and globular, blood-red tipped female blooms grow at shoot tips. Once pollinated by the wind, female flowers turn green and develop into cones.

Crack willow – Salix fragilis

Difficult to distinguish from the white willow, the crack willow—which likes to grow on lowland wet soils, particularly by water and in woods—is so called because of the sound its branches and twigs make as they snap and fall to the ground.

Its narrow, oval, elongated leaves are shorter than those of the white willow and it’s dioecious, with male and female flowers seen on sep- arate trees in May—male catkins are yellow and female catkins green.

English elm – Ulmus minor var. vulgaris

It seems ironic that the billowing, once widespread English elm used to be associated with melancholy and death (possibly because dead branches can fall without warning), only for it to be ravaged by Dutch elm disease in the late 1960s.

With double-toothed, round-tipped leaves, the elm’s blush-tinged, tassel-like flowers appear in February and March and, once pollinated by wind, become winged fruits called samaras that are cast forth in the breeze.

Field maple – Acer campestre

The field maple is Britain’s only native maple—and yes, its sap can be used to make syrup. Often spotted in hedgerows, it can be identified by the five, rounded lobes of its olive leaves—which fade to ochre in autumn—svelte twigs and light-brown, flaky bark.

Its flowers appear to be hermaphrodite, but they’re dominated by either male or female sexual parts, which are small, yellow-green, cup-shaped and hang in clusters. After pollination by insects, they become large, winged fruits, which are scattered by the wind.

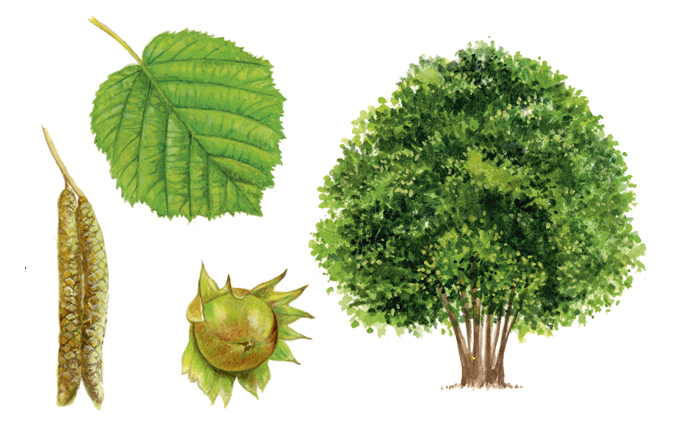

Common hazel – Corylus avellana

Long believed to possess magical powers, the hazel is often coppiced, but can reach 40ft and live for up to 80 years. Long, pale-yellow catkins appear and shed their pollen in February, before toothed and hairy leaves unfurl.

Long believed to possess magical powers, the hazel is often coppiced, but can reach 40ft and live for up to 80 years. Long, pale-yellow catkins appear and shed their pollen in February, before toothed and hairy leaves unfurl.

The hazel’s tiny, female flowers, which are tipped with red stigmas and almost hidden within the leaf-buds, are pollinated by the wind and eventually mature into clusters of up to four brown nuts, each surrounded by jagged-edged green bracts.

Holly – Ilex aquifolium

Glossily evergreen, this much- loved conical-shaped tree, with its prickly, darkest-emerald leaves and bright-red berries (which only adorn female trees), has been used as a winter decoration since pre-Christian times. The thickness and waxy surface of its leaves help them to resist water loss and last up to four years on the tree, which explains how sprigs and wreathes can survive the festive season.

Seen as a fertility symbol and a charm against witches and goblins, cutting down a holly tree—which only has spiky leaves at the bottom to desist browsing animals—was considered unlucky.

Hornbeam – Carpinus betulus

Often confused with common beech, but the buds on winter twigs of hornbeam lie flat, rather than sticking out at a wide angle as with beech. A fluted trunk also distinguishes the tree, along with hanging clusters of triangular, ribbed nutlets ringed by long, three-lobed bracts.

Often confused with common beech, but the buds on winter twigs of hornbeam lie flat, rather than sticking out at a wide angle as with beech. A fluted trunk also distinguishes the tree, along with hanging clusters of triangular, ribbed nutlets ringed by long, three-lobed bracts.

Male (dangling catkins) and female (leafy buds) form on the same tree and, after pollination by the breeze, female catkins become green-winged fruits known as samaras.

Horse chestnut – Aesculus hippocastanum

Introduced to Britain from Turkey in the 1600s, the horse chestnut is more common in parks, gardens, along roads and on village greens than in woodland.

Towering up to 130ft and living as long as 300 years, it’s easily identified by its handsome palmate leaves comprising five to seven pointed, toothed leaflets and the arresting ‘candles’—spears of white blossom, with a pink flush at the base—that adorn it from May. Once pollinated by insects, each flower becomes a burnished red-brown conker encased in a spiky acid-green husk, which falls in autumn

Common alder – Alnus glutinosa

I’m fond of the dark-green, round- leaved alders that escort the rivers that wind down from the moor, below our house in the Scottish borders, en route to the Border Esk. One of the few trees on which leaves stay verdant well into the autumn, it’s the alder’s catkins that make it stand out from the rest of the trees in the wood. Although the fruits ripen in October, they remain throughout the winter as brown, woody cones, until the seeds are dispersed in spring.

Common ash – Fraxinus excelsior

The ash is one of our tallest trees, easily distinguished by fronds of 6–13 avocado-coloured toothed leaf- lets that sit opposite each other. Look out for short, black buds in opposite pairs on smooth, grey twigs.

The ash, on which spiked clusters of purple-tipped flowers usually appear on different trees, but, paradoxically, can develop male and female flowers on different branches of the same tree, is susceptible to ash dieback. Once pollinated by the wind, these flowers become winged fruits known as ‘keys’.

Aspen – Populus tremula

Also known as ‘quaking aspen’, possibly due to the way its small leaves—which are borne singly on long, flattened stalks—tremble in the breeze, creating a rustling sound, the aspen’s leaves are a coppery-brown shade when they first unfurl in spring, fading to amber in autumn.

With dainty trunks cloaked in silvery-green bark, often pitted with diamond-shaped pores called lenticels, individual aspens produce exclusively male and female flowers (catkins) in March or April, before the leaves appear. Fertilised female catkins ripen during the summer, before releasing tiny, tufted seeds.

Rowan – Sorbus aucuparia

The rowan is a graceful, open tree with smooth, grey-brown bark and pinnate (feather-like) leaves comprising eight pairs of long, oval and toothed leaflets. Its extreme hardiness— which means that, along with the silver birch, it can be found higher up on mountainsides than any other tree in Britain—explains why it’s sometimes known as the mountain ash.

Widely planted as a street or garden tree, it’s a hermaphrodite and comes into its own in May, when clusters of white blossom spread over the crown. By September, these have become the lipstick-red berries that make a great jelly to go with game.

Sessile oak – Quercus petraea

So-called due to its stalkless (sessile) acorns, Britain’s second native oak is usually found in less fertile upland areas. When mature, it forms a broad and spreading crown and tends to be taller, with a more elongated, straighter trunk, than an English oak.

So-called due to its stalkless (sessile) acorns, Britain’s second native oak is usually found in less fertile upland areas. When mature, it forms a broad and spreading crown and tends to be taller, with a more elongated, straighter trunk, than an English oak.

Male and female flowers are found on the same tree, with male flowers forming green catkins and females appearing as discreet clusters of bracts (modified leaves), which resemble red flower buds.

Silver birch – Betula pendula

Easily recognisable as one of Britain’s native trees, thanks to its slender trunk and pearly-white bark, the silver birch grows higher up mountains than any other deciduous tree.

Easily recognisable as one of Britain’s native trees, thanks to its slender trunk and pearly-white bark, the silver birch grows higher up mountains than any other deciduous tree.

Its delicate leaves, with a straight base and large teeth, alternate along slim, whip-like, red-brown twigs and the branches usually droop downwards, hence the Latin name pendula, which means hanging. In winter, when viewed en masse from a distance, the naked branches of this feminine and graceful tree radiate a soft, purple hue.

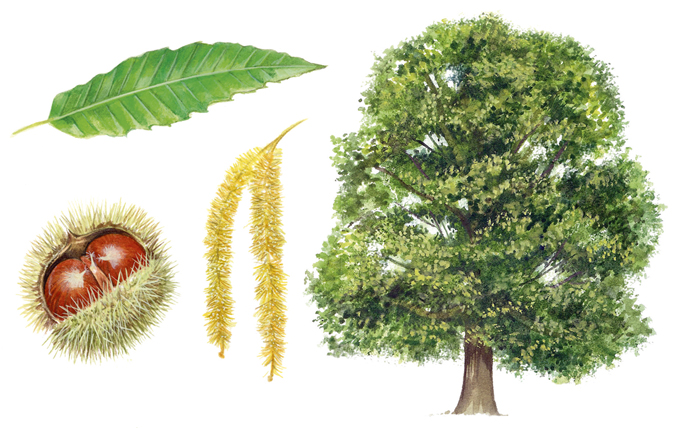

Sweet chestnut – Castanea sativa

Widespread in coppices and park- lands, but rare in the North and West, the sweet chestnut has grown in Britain since Roman times. As cool British summers prevent nuts ripening, most chestnuts eaten in the UK are imported. Large, narrow trees with long and slim leaves, saw-like teeth and parallel veins and lots of low branches, sweet chestnuts punctuate parks or former parkland.

Widespread in coppices and park- lands, but rare in the North and West, the sweet chestnut has grown in Britain since Roman times. As cool British summers prevent nuts ripening, most chestnuts eaten in the UK are imported. Large, narrow trees with long and slim leaves, saw-like teeth and parallel veins and lots of low branches, sweet chestnuts punctuate parks or former parkland.

Unusually, its catkins bear mostly male flowers and others have both male and female—female flowers form at the base and tassel-like male flowers at the tip of the catkin, which in autumn, develops into a spiky husk containing up to three nuts.

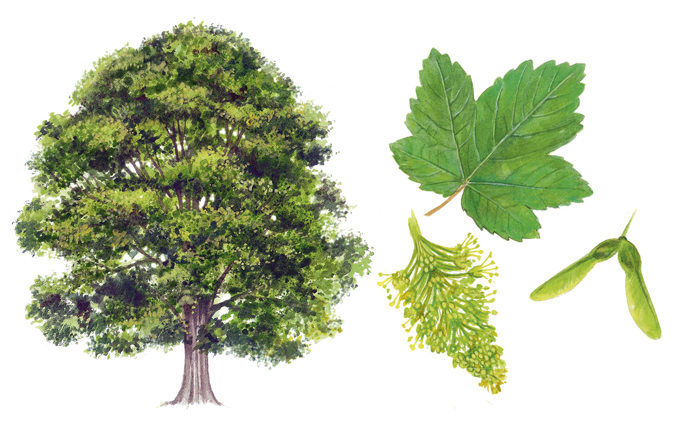

Sycamore – Acer pseudoplatanus

Introduced from France in the Middle Ages, the sycamore is a common sight in woodlands and gardens. Set apart by its winged fruits, which, in October spiral to the ground rather like helicopter blades, this tree—with a massive domed outline and dense foliage—is also distinguished by its dark green, leathery-like toothed leaves, which don’t look unlike those of the maple. Greenish-yellow flowers appear, along with the leaves, in May and June.

Introduced from France in the Middle Ages, the sycamore is a common sight in woodlands and gardens. Set apart by its winged fruits, which, in October spiral to the ground rather like helicopter blades, this tree—with a massive domed outline and dense foliage—is also distinguished by its dark green, leathery-like toothed leaves, which don’t look unlike those of the maple. Greenish-yellow flowers appear, along with the leaves, in May and June.

Yew – Taxus baccata

Long associated with churchyards, the yew can reach 600 years of age, with some British specimens pre-dating the 10th century. A symbol of immortality, but also a harbinger of doom, the yew has small, ramrod- straight needles with pointed tips that grow in two rows on either side of each twig.

Long associated with churchyards, the yew can reach 600 years of age, with some British specimens pre-dating the 10th century. A symbol of immortality, but also a harbinger of doom, the yew has small, ramrod- straight needles with pointed tips that grow in two rows on either side of each twig.

Male and female flowers—which grow on separate trees—appear in March and April. The yew doesn’t bear its seeds in a cone; each seed is enclosed in a red, fleshy, berry-like structure known as an aril, the only part of the tree that’s not toxic.

If you liked our simple guide to identifying British trees you might also like:

At long last Spring seems to be here — and with it, the natural flora that give so much pleasure.

Are you able to tell your woolly bears from your elephant trunks?

A simple guide to the wildflowers of Britain

Common caterpillars: A simple guide