-

A one-of-a-kind waterfront estate with two private beaches is for sale on the same storied American island that Jackie Kennedy, the Obamas and Princess Diana have all visited

By Rosie Paterson

-

-

Snakes alive! Country Life Quiz of the Day, July 15, 2025

By Country Life

-

The truth about P.G. Wodehouse: Robert Daws on playing England's greatest comic writer

By Toby Keel

-

Five British gardens have a starring role on the New York Times's list of 25 must-see gardens — here are the ones they forgot

By Lotte Brundle

-

The architect who created the MI6 building only designed a tiny handful of houses — and one of them is now up for sale in one of London's most bucolic spots

By Toby Keel

-

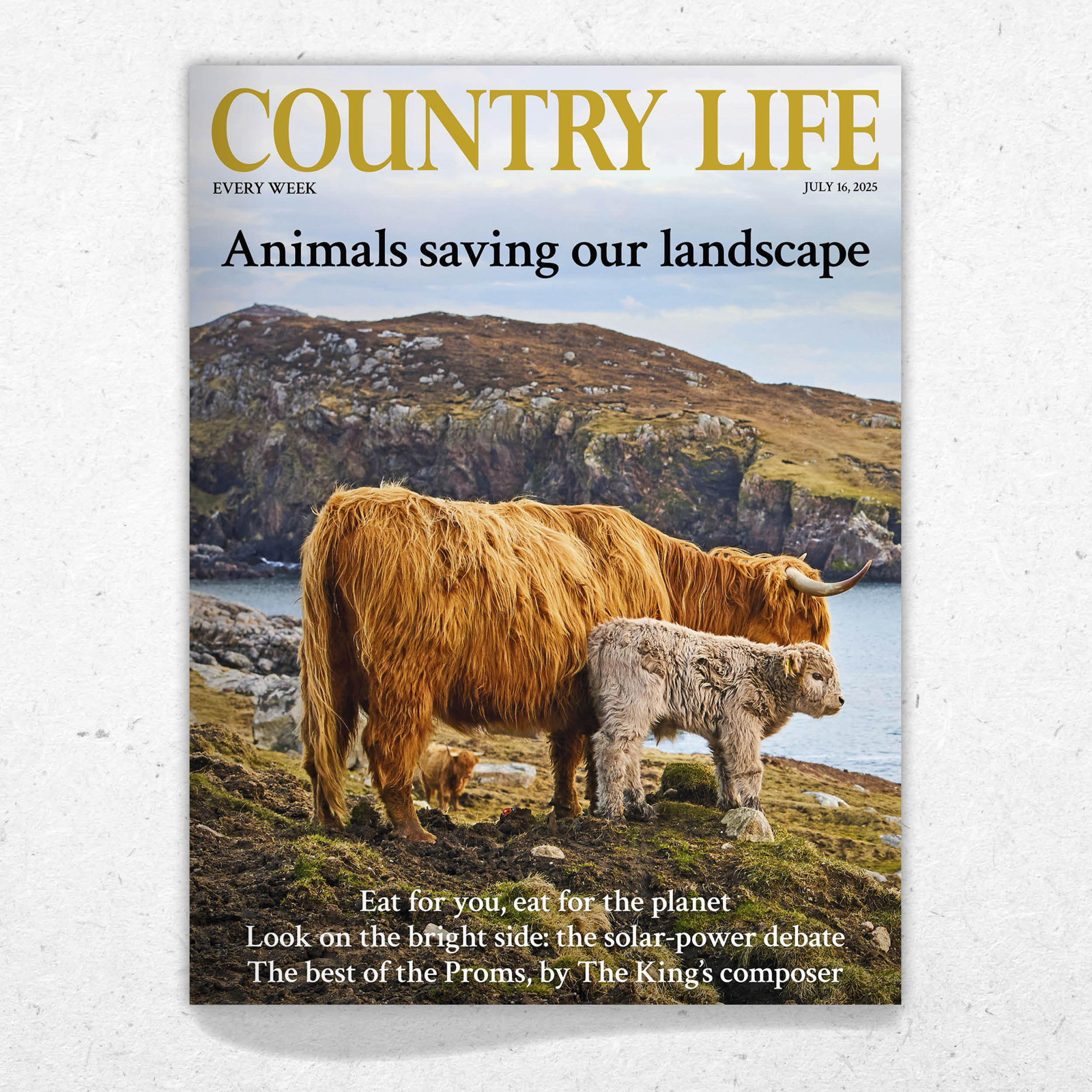

This week's issue of Country Life — and how to subscribe or get your copy

By Country Life

-

The teeny tiny car that you absolutely don’t need, but will absolutely want this summer — and it has an inbuilt shower

By Rosie Paterson

-

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

People & Places

-

-

‘‘In the silence, it is the most perfect blue I have ever seen. If my goggles weren’t already overflowing with water I might even weep’: Learning to freedive on the sparkling French Riviera with a five-time World Champion

-

West London's spent the last two decades as the laughing stock of the style set — here's how it got its groove back

-

‘To this day, it is as attractive as when Hercules first laid eyes on it’: How to escape the crowds on the Amalfi Coast, according to those in the know

-

Brat behaviour: The chef behind Shoreditch institution Brat and Soho favourite Mountain is running away to Wales

-

Property

View all Property-

A one-of-a-kind waterfront estate with two private beaches is for sale on the same storied American island that Jackie Kennedy, the Obamas and Princess Diana have all visited

By Rosie Paterson

-

-

The architect who created the MI6 building only designed a tiny handful of houses — and one of them is now up for sale in one of London's most bucolic spots

By Toby Keel

-

'True waterfront homes are finite... miss one and it could be years before you see another like it again': Why the best waterfront property always hits the spot

By Annabel Dixon

-

19 charming homes for sale, from picture-perfect cottages to beachside retreats, as seen in Country Life

By Toby Keel

-

Tim Burton is selling the house he shared with Helena Bonham-Carter, a sublime home on the Thames that comes with three private islands

By Rosie Paterson

-

A spectacular tower for sale that's a blend of Victorian folly, architectural marvel and 21st century family home

By Toby Keel

-

The former stables — and recording studio for the Pet Shop Boys — transformed with a magical blend of city and country aesthetic, now seeking a new owner

By Toby Keel

-

Our expert voices

Interiors

View All Interiors-

21 of the greatest craftspeople working in Britain today, as chosen by the nation's best designers and architects

By Giles Kime

-

-

The transformative renovation of a Grade II-listed property with an 'unusual footprint'

By Arabella Youens

-

I've seen the light: How a dark and gloomy kitchen in the Scottish Borders was reconfigured for 21st century living

By Arabella Youens

-

'Comfortable, cosseting and far from the madding crowd': The recently refurbished Cornish cottage that proves Victorian decor is making a comeback

By Giles Kime

-

18 inspiring ideas to help you make the most of meals in the garden this summer

By Amelia Thorpe

-

'These aren't just rooms. They are spaces configured with enormous cunning, artfully combining beauty with functionality': Giles Kime on the wonders of WOW!house 2025

By Giles Kime

-

How the deep-lustre of copper brings period glamour to this kitchen

By Arabella Youens

-

The beauty’s in the detail: How English stone specialist Artorius Faber helped to bring Country Life's Chelsea stand to life

By Artorius Faber

SPONSORED

-

LIFE & STYLE

View All LIFE & STYLE-

-

The teeny tiny car that you absolutely don’t need, but will absolutely want this summer — and it has an inbuilt shower

By Rosie Paterson

-

‘It only remains for our descendants to curse our impotence and laissez-faire’: Only four photographs of a storied London townhouse survive inside the Country Life archive — and it was brutally demolished not once, but twice

By Melanie Bryan

-

You can’t always rely on the Great British summer — but you can rely on its watches

By Chris Hall

-

No strings attached: A brief history of swimwear, from heavy skirts of linen linked to women's drownings, to the skimpy two-piece named after a nuclear weapons site

By Deborah Nicholls-Lee

-

COUNTRYSIDE

View All THE COUNTRYSIDE-

-

The truth about P.G. Wodehouse: Robert Daws on playing England's greatest comic writer

By Toby Keel

-

Puffins and shearwaters, skuas and terns, gannets and gulls and guillemots and wings, these are a few of our favourite things (seabirds)

By John Lewis-Stempel

-

The red kite is a soaraway success story, having escaped extinction to become a familiar sight in our skies again

By Mark Cocker

-

Gardens

View All Gardens-

Five British gardens have a starring role on the New York Times's list of 25 must-see gardens — here are the ones they forgot

By Lotte Brundle

-

-

The garden created by a forgotten genius of the 1920s, rescued from 'a sorry state of neglect to a level of quality it has not known for over 50 years'

By George Plumptre

-

Alan Titchmarsh: My garden is as pretty as I've ever known it, thanks to an idea I've rediscovered after 50 years

By Alan Titchmarsh

-

The Hollywood garden designers who turned their hand to a magical corner of Somerset

By Caroline Donald

-

Sarah Raven: The flowers I have that are flourishing superbly, despite the battering heat

By Sarah Raven

-

The 'Rose Labyrinth' of Coughton Court, where 200 varieties come together in this world-renowned garden in Warwickshire

By Val Bourne

-

ART & CULTURE

View all ART & CULTURE-

-

‘One of the most effective pieces of propaganda ever made’: the Bayeux Tapestry heads to Britain for the first time in almost a millennium

By Carla Passino

-

‘They remain, really, the property of all of those who love them, know them, and tell them. They are our stories, the inheritance of the people of Scotland’: The Anthology of Scottish Folk Tales

By Patrick Galbraith

-

Canine muses: Lucian Freud's etchings of Pluto the whippet are among his most popular and expensive work

By Agnes Stamp

-

‘Reactions to the French in the 1870s varied from outrage to curious interest’: Impressionism's painstaking ten year journey to be taken seriously by the Brits

By Caroline Bulger

-

Travel

View All Travel-

Beyond Royal Portrush: Castles, country houses and ancient towers in the other dimension of golf in Ireland

By Toby Keel

-

-

‘To this day, it is as attractive as when Hercules first laid eyes on it’: How to escape the crowds on the Amalfi Coast, according to those in the know

By Luke Abrahams

-

The 'strikingly beautiful, authentic and innovative' Highland castle that's been saved for the ages, and available to rent by the weekend

By Mary Miers

-

Jnane Rumi, Marrakech, hotel review: 'The most talked about opening this year — and for good reason'

By Christopher Wallace

-

‘‘In the silence, it is the most perfect blue I have ever seen. If my goggles weren’t already overflowing with water I might even weep’: Learning to freedive on the sparkling French Riviera with a five-time World Champion

By Chris Cotonou

-

'Champagne is not simply a place, it’s a symbol of excellence': How a quiet rural region shrugged off war, famine and pestilence to become the home of the ultimate luxury tipple

By Lotte Brundle

-

Food & Drink

View All Food & Drink-

Tom Parker Bowles: This 90-year-old Italian restaurateur makes the world's best sorbet and granita

By Tom Parker Bowles

-

-

Brat behaviour: The chef behind Shoreditch institution Brat and Soho favourite Mountain is running away to Wales

By Will Hosie

-

The last miracle of St Boswell? How a Scottish potato field became the world's least-likely producer of sparkling wine

By Lotte Brundle

-

How to make The Connaught Bar's legendary martini — and a few others

By Rosie Paterson

-

Gill Meller's tomato, egg, bread and herb big-hearted summer salad

By Gill Meller

-

Sophia Money-Coutts: Why clinking glasses and saying ‘Cheers!’ is a tiny bit embarrassing

By Sophia Money-Coutts

-

What do an order of Catholic priests and actor Hugh Bonneville have in common? They helped this West Sussex sparkling wine triumph over multiple French Champagne houses

By Lotte Brundle

-