Revealed during a Victorian shooting party, the remains of Chedworth Villa offer a vivid insight into country living in the Roman Cotswolds, says Bronwen Riley.

When out shooting one day in the winter of 1863–4, James Farrer MP was astonished when his loader, a gamekeeper called Margetts, produced some Roman mosaic tesserae. These, it was revealed, had been found in the surrounding woods. Farrer was uncle and guardian to the 3rd Lord Eldon, who owned the Stowell estate where the shoot was taking place. A keen antiquarian, he began to excavate the site the following summer. With tremendous energy and a team of some 50 labourers he soon uncovered a substantial Roman villa.

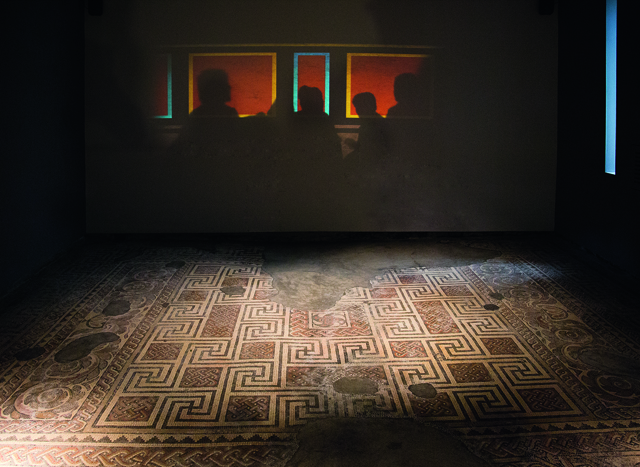

By modern archaeological standards, his nestling in a quiet combe of the Cotswold excavation methods were lamentable: the men used pickaxes and shovels to clear the ruins, discarding or destroying much valuable evidence. In the process, however, they uncovered a series of mosaics and numerous obvious finds. What Farrer did next, however, was innovative. He preserved the mosaics in situ, covering them for protection, and built a museum in the centre of the site to display the finds.

Soon after, Lord Eldon made the villa a feature of his estate by appending a shooting lodge to Farrer’s museum in about 1867, built on the spoil removed in uncovering the villa. He transformed the surroundings, providing a large turning circle for carriages and planting specimen trees and parterres around the lodge. The mosaics provided a conversation piece for his shooting parties, just as they presumably had done for the master of the 4th-century villa, when he invited friends over to hunt on his estate.

Nestling in a quiet combe of the Cotswold countryside overlooking the River Coln and surrounded by woodland, today, the villa seems tucked away from the outside world. In the mid 4th century, however, the house was one of hundreds of villas in the area and was well served by a network of roads that linked to Corinium Dobunnorum (Cirencester), the second largest town in Britain after London and the possible provincial capital of Britannia Prima (the former province of Britannia having been divided into four).

The villa’s size and proximity to Cirencester might identify its owner as a figure in the imperial administration. In the first centuries after the conquest of Britain, power had been devolved to local Romanised elites, but, by the 4th century, imperial government had become far more centralised, with a vastly expanded civil service. Chedworth’s owner, therefore, could either have been a descendant of the pre-Conquest British ruling class who had managed to maintain power and status under the Roman system or a senior bureaucrat born outside Britain.

Alternatively, Chedworth may have been owned by a largely absentee landlord from abroad, someone like the future St Melania the Younger, born in the 380s into a fantastically rich senatorial family in Rome, who held extensive estates in Britain, Gaul, Spain and Sicily before she renounced them all and embraced Christianity.

Although we do not know the name or origin of the owner, what remains of the villa shows us that whoever it was had fully signed up to the Roman way of life. Here, in deepest Gloucestershire, the owner could indulge in civilised otium, or leisure, doing just what Roman aristocrats had been doing since the days of the Republic—hunting, dining, improving their estates and displaying their taste and learning to their guests.

The villa and its surrounding buildings would have sat prominently within the largely open, farmed landscape. On the ridge over the valley was an imposing monument (possibly a mausoleum), while a square Romano-British temple stood some 850 yards from the villa on the slopes overlooking the Coln. An adjacent spring supplied the villa with water and was overbuilt with a shrine to the nymphs— a nymphaeum—although it may also have been sacred to a British water deity.

A coping stone from the basin was incised with XP, the first two Greek letters of Christ’s name, indicating that the spring was Christianised, probably during the reign of Emperor Constantine I (306–337). Intriguingly, the stone was found reused in the Roman buildings, perhaps indicating that enthusiasm for Christianity had been short-lived at Chedworth.

Visitors approaching the villa would have seen a large house rising above them on a series of terraces. The buildings were laid out on a U-shaped plan with long parallel north and south wings connected by a shorter west range. A gallery with a central gatehouse bisected the central courtyard into an upper and lower area. The west range and north wing —part of which is shown re-created here— housed the main reception rooms.

View of the bathhouse in the west range. A tree stump was preserved during the 19th-century clearance, a reminder that the villa had been entirely overgrown. National Trust Images.

Access to these well-appointed interiors, many decorated with mosaics, was provided by covered galleries. Some protection from the elements was necessary because, from November to March, the valley would have spent much of its time in shade. It is likely that the villa’s inhabitants remained in town during the winter months. Certainly, if Cirencester followed imperial Rome’s traditional calendar, then November to March would have been months when elections were held, new appointments made and games given.

The west range looked straight down over the valley. At its southern end was a triclinium, or dining room, with a fine mosaic floor heated by a hypocaust. At its northern end was a bath house, which was also richly decorated with mosaics and wall paintings. Although guests had originally dined reclining on three couches (the derivation of the word triclinium), by the 4th century, they generally occupied a semi-circular couch or stibadium in strict order of social precedence. In both arrangements, the mosaic would have been a prominent feature of the room.

At Chedworth, the mosaic subject is of myths associated with Bacchus, god of wine. Four panels show the Seasons personified, with Winter appropriately enough clad in a heavy byrrus Britannicus, the renowned British hooded cape. British textiles were highly regarded and exported throughout the empire. A host would be judged not only on the quality of his interior decoration, but also on that of his food and wine. One dish that seems to have been on the menu was snails, judging by the numbers of Helix pomatia still living around the villa in the 21st century.

Before dinner, host and guests would have bathed. The baths worked in a fashion similar to Turkish baths. Bathers would undress and be covered in oil before progressing through a series of rooms that became gradually hotter. Having reached the caldarium, the hot steam room, they would scrape off oil and dirt with a curved metal tool called a strigil before returning to the cold room to take a plunge in a cold bath.

The north wing, which is some 330ft long, faces south to catch the sun. This range also contained a bathing and dining suite, the latter providing views over the valley on a warm summer evening. The bathing rooms here are of slightly different type to those in the west wing and contain a laconicum or very hot dry room, like a sauna. Having two sets of baths may have enabled men and women to bathe separately or perhaps simply offered different bathing and entertaining experiences—bathing was, after all, a sociable pursuit.

Although the summer dining room in the north range seems to have been provided with a small adjoining kitchen, the principal domestic area was in the south wing. The main kitchen was situated near the dining room and had a large stone-and-clay oven just inside the door. A small communal latrine lay just off the kitchen —a common arrangement (elsewhere there is evidence for latrines being situated inside kitchens so that they could both use the same drain).

Unfortunately, the fervour of Farrer’s excavation probably swept away vital clues relating to other ancillary buildings we would expect to find associated with a villa of this size. Gone is all trace of the barns, stables and accommodation for estate workers. Hints as to what was produced here come in the form of carbonised grain that seems to have been processed on a large scale.

The estate would have needed arable land for crops and pasture and water for the animals, as well as carefully managed woodland, essential for providing building materials, fuel and for raising game.

Numerous antlers, together with statues of Diana the huntress and of Silvanus, a god of woodland, who is also associated with hunting, suggest that this was a favourite pastime. Breeds of British hunting dogs were held to be ugly but highly effective and were exported throughout the empire.

In 2011, the National Trust embarked on an ambitious conservation programme at Chedworth. It was faced with an interesting dilemma, namely, how best to present the Roman villa using modern conservation methods while accepting that the villa sat in a Victorian landscape which itself was of historic interest. The Trust decided to replace the Victorian cover buildings of the west range, which were no longer providing adequate protection, with a new timber shelter that would evoke the layout of the 4th-century villa, but which makes no impact on its archaeology. They kept the Victorian specimen trees, but softened the landscape, allowing long grass to grow in the area around the villa and within the north range.

The Trust also embarked last year on a five-year research plan supported by English Heritage to better understand the north range. This August, a large, late-Roman mosaic was uncovered here, together with fragments of painted wall plaster, confirming the hypothesis that this had been a large reception room. In this, the 150th year since Farrer’s discovery of the site, it is thrilling to know that the villa still holds many more revelations.

Acknowledgements: Simon Esmonde Cleary. ‘A Journey to Britannia’ by Bronwen Riley will be published by Head of Zeus in March 2015.