-

From Claudia Winkleman to the Komondor, here are the 10 things to look out for at Crufts 2026

By Agnes Stamp -

-

A right royal affair with the stars

By Matthew Dennison -

Where has the biggest population — Sweden or Switzerland? Find out in the Country Life Quiz of the Day, March 3, 2026

By Country Life -

These are a few of James Middleton's favourite things

By Amie Elizabeth White -

Thomas Gainsborough means one thing in Britain. He means another in America

By Owen Holmes -

What you'll find in this week's issue of Country Life — and how to subscribe or get your copy

By Country Life -

A Georgian home with a Laurence Llewelyn-Bowen living room that brings a touch of Hogwarts to one of the greenest parts of London

By Toby Keel

-

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

People & Places

-

-

The life of a BAFTA begins in an industrial estate in Braintree

-

The W1 set is up in arms about Liz Truss's roof terrace. But what is a members' club without one?

-

What have the Romans ever done for us? For one thing, taught us the art of seduction

-

‘I’m like: “Give me those tights, let me show you”: Ballet superstar Carlos Acosta’s consuming passions

-

Property

View all Property-

A Georgian home with a Laurence Llewelyn-Bowen living room that brings a touch of Hogwarts to one of the greenest parts of London

By Toby Keel -

-

A Somerset country home that unites the best of medieval, Georgian and Victorian under one roof

By Toby Keel -

Five magical country homes for sale across Britain, as seen in Country Life

By Toby Keel -

A spectacular home with a touch of Downton Abbey about it, standing beside one of the last remaining Saxon churches in Britain

By Toby Keel -

A Caribbean home with its own nightclub, down the road from a perfect beach and a pre-Columbian castle

By Toby Keel -

Alan Carr's new castle is 'a masterpiece of the baronial revival' with 17 bedrooms and its own miniature railway

By Toby Keel -

A house that's the epitome of the Yorkshire dream, in the heart of the county's 'Golden Triangle'

By Arabella Youens

-

Architecture

View all Architecture-

Gibside: The curious roofless castle where The King's ancestor was kidnapped

By Melanie Bryan -

-

'A blue-blood background and a drive to disrupt': Lady Violet Manners on the importance of preserving Britain's privately-owned country homes

By Owen Holmes -

A Suffolk home where glass, steel, timber and thatch come together in perfect harmony

By Clive Aslet -

Why has everyone fallen under the spell of Wrotham Park — one of the largest private houses inside the M25

By Laura Kay -

Refurbishing the Palace of Westminster will be extremely expensive, but so too will be doing nothing

By Athena -

What binds the Queen Mother and Chicago's first department store? A lost Scottish castle that was blown to smithereens by the Territorial Army

By Melanie Bryan -

The only thing better than a stately home is a stately home in wooden miniature

By Will Hosie -

'I have never ceased talking of the beauty of Ampthill': The tale of one of Britain's best-loved country houses

By Jeremy Musson

-

Our expert voices

Interiors

View All Interiors-

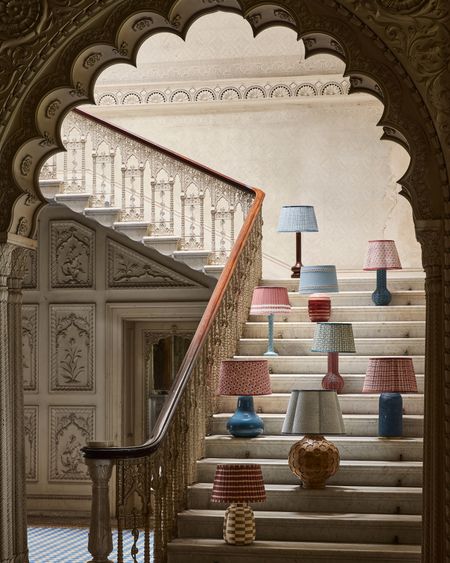

New designs and accessories to brighten every room

By Amelia Thorpe -

-

London Design Week: What to look out for at next month's unmissable interiors event

By Amelia Thorpe -

How do you add historic character back into a soulless room?

By Arabella Youens -

This clever interiors trick is the secret to creating multifunctional spaces — and it was integral to the design of many English country houses of the past

By Giles Kime -

'It was a complete wreck': Reclaiming a Hampshire coaching house from the earth

By Arabella Youens -

How do you add a dash of theatricality to a 1930s house? By taking inspiration from the legendary architect and set designer Oliver Messel

By Arabella Youens -

Are you a curator, a sympathiser or a conscientious objector? Take our Interiors Editor's quiz to discover your design DNA

By Giles Kime -

‘The pair drove to Belgium in their Mini and returned with the chair wrapped in duvets’: The mother-and-daughter duo that brought a converted Cotswolds barn back to life

By Arabella Youens

-

Gardens

View All Gardens-

'It was the only design that spoke the same language as the house. It immediately felt right': An Oxfordshire home where house and garden work in perfect, asymmetrical harmony

By Tiffany Daneff -

-

You don’t need to live in the countryside or have acres of space to start a cutting garden

By Amy Merrick -

Intrepid, enterprising, dedicated: The new generation of nursery owners creating the flowers we'll be enjoying for decades to come

By John Hoyland -

Alan Titchmarsh: Patience is in short supply today, but learning when to crack on and when to leave well alone will do your garden wonders

By Alan Titchmarsh -

Penns in the Rocks: The East Sussex garden created by Vita Sackville-West, with a little help from the huge boulders that stood here when dinosaurs walked the earth

By George Plumptre -

'I was utterly bewitched': The heartwarming success story of one of Britain's greatest rose-growers

By Charles Quest-Ritson

-

LIFE & STYLE

View All LIFE & STYLE-

-

From Claudia Winkleman to the Komondor, here are the 10 things to look out for at Crufts 2026

By Agnes Stamp -

Driving is an occasion. It's time to dress like it

By Simon De Burton -

Almanza Backseat Driver, Collooney Tartan Tease, Burneze Geordie Girl: What it takes to be crowned Best in Show at Crufts (apart from a very long name)

By Florence Allen -

It is the ‘year of the tiara’, but what’s a girl (or guy) to do if they don’t have an heirloom laying about?

By Felix Bischof

-

THE COUNTRYSIDE

View All THE COUNTRYSIDE-

-

What is everyone talking about this week: Longevity? I think farmers invented that...

By Will Hosie -

Nature’s symbiotic relationships are as multifarious as they are marvellous

By John Lewis-Stempel -

The winter Olympians of the natural world

By Rosie Paterson

-

ART & CULTURE

View all ART & CULTURE-

-

A right royal affair with the stars

By Matthew Dennison -

Thomas Gainsborough means one thing in Britain. He means another in America

By Owen Holmes -

Sir Antony Gormley: Why I am continually captivated by Adriaen de Vries’s radical sculpture Antiope and Theseus

By Sir Antony Gormley -

'He was a French artist enamoured with light and colour, movement and lightness'

By James Fisher

-

Travel

View All Travel-

There are more than 100 species of lemur living on the world's fourth-largest island — and they cannot be found anywhere else on Earth

By Rupert Uloth -

-

In the battle of travel tour operator versus AI, who will win?

By Rosie Paterson -

Hôtel du Couvent: This former convent on the French Riviera has rekindled the rules of luxury

By James Fisher -

This Hollywood star's home in the Canadian wilderness is now an exclusive-use lodge

By Rosie Paterson -

The real challenge facing Britain's grande dame seafront hotels

By Athena -

Couples are changing how they holiday — even on honeymoon

By Rosie Paterson

-

Food & Drink

View All Food & Drink-

A very brief history of brown sauce

By Harry Pearson -

-

Forget museums, the pub is where real history happens

By Ashleigh Arnott -

It's alive! The UK producers embracing fermentation to make delicious products teeming with life

By Tom Howells -

‘French pastries all look amazing… but I wish more British bakers would look at what we used to have’: Richard Hart on the joys of jammy dodgers and iced buns

By Oliver Berry -

Where's the rum gone? How the temperance movement took on the Royal Navy

By Henry Jeffreys -

Tom Parker Bowles: 'There is no dish more lusty and full blooded than boeuf à la Bourguignonne'

By Tom Parker Bowles -

The 'chef's table' is off the ick list

By Emma Hughes

-