-

Lodge Park: Megève is where snow and style mingle, and this hotel is at the heart of it all

By James Fisher -

-

‘I don't consider myself to be a nepo baby at all’: Caroline Avedon on preserving her grandfather's legacy — and her consuming passions

By Lotte Brundle -

When is a cottage not a cottage? When it's a spectacular, glass-walled lakehouse making waves in 'Heated Rivalry'

By Will Hosie -

How well do you really know Country Life? Test your knowledge of your favourite magazine in Quiz of the Day, February 6, 2026

By Country Life -

'To my unspeakable disgust and pain, the little inconsiderate beast squirted his acid down my throat': The army of animals weaponising chemistry in the fight for survival

By Deborah Nicholls-Lee -

New kids on the block: London's hotel boom and the new openings around the world to have on your radar

By Rosie Paterson -

The 'chef's table' is off the ick list

By Emma Hughes

-

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

People & Places

-

-

Jenson Button: 'Get rid of your ego'

-

'The Shakespeare of architects... he has yet had no equal in this country': Sir John Vanbrugh and the legacy of Blenheim Palace

-

These are a few of Diana Henry's favourite things

-

Sophia Money-Coutts: A snob's guide to supermarkets and what to do when there's no Waitrose

-

Property

View all Property-

When is a cottage not a cottage? When it's a spectacular, glass-walled lakehouse making waves in 'Heated Rivalry'

By Will Hosie -

-

A picture-perfect thatched cottage tucked away in Dorset's Blackmore Vale

By Julie Harding -

The nearest thing you'll find to a tropical lodge in London? This exotic home is right on the Thames, and 10 miles from the centre of the city

By Julie Harding -

A Grade II-listed farmhouse just outside the Cornwall village dubbed 'Hollywood-on-Sea', on sale for the first time in 500 years

By Toby Keel -

Best country houses for sale this week

By Country Life -

'We made the mistake of accepting the word of a surveyor. Off we went on a voyage of restoration lasting 30 years': Griff Rhys-Jones on his first house in the country

By Arabella Youens -

A Georgian home that's the epitome of the country house dream, with four-poster beds, Aga and pool, set in one of Britain's most sought-after spots

By Arabella Youens

-

Architecture

View all Architecture-

The striking Arts & Crafts country home with interiors by William Morris that disappeared without a trace

By Melanie Bryan -

-

'The Shakespeare of architects... he has yet had no equal in this country': Sir John Vanbrugh and the legacy of Blenheim Palace

By Charles Saumarez Smith -

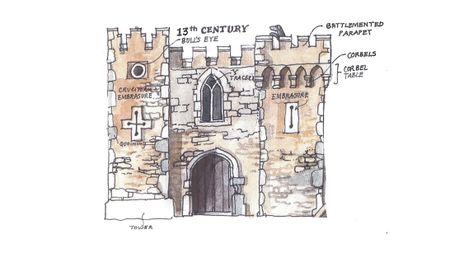

Can you tell the difference between a trefoil and an embrasure? A pictorial guide to medieval architecture

By Toby Keel -

Lord Byron, Charles Dickens and Sir Walter Scott once dined at this Jacobean mansion in London. Destroyed by The Blitz it lives on now only in the Country Life Archive

By Melanie Bryan -

'Climbing is to ascend not only through space, but through centuries of lineage': The great staircases of Britain's finest country houses

By Melanie Cable-Alexander -

The Picturesque Scottish castle built on land admired by Robert Burns and erased by war

By Melanie Bryan -

Portmeirion: A century of peculiar genius at Clough Williams-Ellis's great village experiment

By Kathryn Ferry -

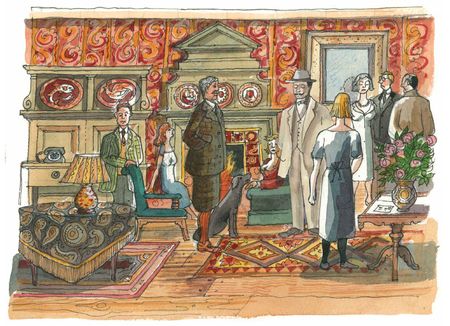

The great country houses which inspired the tales of Agatha Christie, 50 years on from her death

By Jeremy Musson

-

Our expert voices

Interiors

View All Interiors-

This clever interiors trick is the secret to creating multifunctional spaces — and it was integral to the design of many English country houses of the past

By Giles Kime -

-

'It was a complete wreck': Reclaiming a Hampshire coaching house from the earth

By Arabella Youens -

How do you add a dash of theatricality to a 1930s house? By taking inspiration from the legendary architect and set designer Oliver Messel

By Arabella Youens -

Are you a curator, a sympathiser or a conscientious objector? Take our Interiors Editor's quiz to discover your design DNA

By Giles Kime -

‘The pair drove to Belgium in their Mini and returned with the chair wrapped in duvets’: The mother-and-daughter duo that brought a converted Cotswolds barn back to life

By Arabella Youens -

'You should need little reminding that the 1980s are back': Country Life's interior-design predictions for 2026

By Giles Kime -

How an eco-friendly interior designer transformed a former milking parlour into a multi-purpose space in the middle of the Pandemic

By Grace McCloud -

How Britain’s biggest and best country houses are decking the halls (and façades) for Christmas

By Bella Fulford

-

Gardens

View All Gardens-

'I was utterly bewitched': The heartwarming success story of one of Britain's greatest rose-growers

By Charles Quest-Ritson -

-

William Robson, the visionary gardener 150 years ahead of his time

By Tiffany Daneff -

'It was like going on a blind date... over a few glasses of wine our friendship was sealed and by three in the morning we had a plan': The creation of a spectacular Moroccan garden

By Kirsty Fergusson -

Alan Titchmarsh: I'm always asked about 'creating a sensory garden', and my answer is always the same

By Alan Titchmarsh -

The gardeners' gardens: Alan Titchmarsh, Mary Keen, Clive Nichols and more on the places they have on their 2026 hitlists

By Tiffany Daneff -

Beautiful, rewarding, unpronounceable: Chaenomeles, the spectacular shrub that grows happily in gardens where azaleas will never bloom

By Charles Quest-Ritson

-

LIFE & STYLE

View All LIFE & STYLE-

-

Jenson Button: 'Get rid of your ego'

By Matthew MacConnell -

These are a few of Diana Henry's favourite things

By Amie Elizabeth White -

A good call: The red telephone box rings in 100 years

By Deborah Nicholls-Lee -

Audi S e-tron GT: Is this the EV that will save us from a dull and silent future?

By James Fisher

-

THE COUNTRYSIDE

View All THE COUNTRYSIDE-

-

'To my unspeakable disgust and pain, the little inconsiderate beast squirted his acid down my throat': The army of animals weaponising chemistry in the fight for survival

By Deborah Nicholls-Lee -

What you'll find in this week's issue of Country Life — and how to subscribe or get your copy

By Country Life -

The world’s heaviest flying bird flaps on to pastures new but remains endangered, says expert

By Lotte Brundle

-

ART & CULTURE

View all ART & CULTURE-

-

‘I don't consider myself to be a nepo baby at all’: Caroline Avedon on preserving her grandfather's legacy — and her consuming passions

By Lotte Brundle -

Cybele and Juno statues finally return to Stowe's south-front portico

By Julie Harding -

A study in sculpture: 10 of the finest pieces from the Royal Collection

By Sir Jonathan Marsden -

A mesmerising portrait in the eerie country house that inspired Charlotte Brontë to write 'Jane Eyre'

By John Goodall

-

Travel

View All Travel-

Lodge Park: Megève is where snow and style mingle, and this hotel is at the heart of it all

By James Fisher -

-

New kids on the block: London's hotel boom and the new openings around the world to have on your radar

By Rosie Paterson -

'It’s worth remembering that our closest surroundings often hold multitudes of their own'

By Ben Lerwill -

The Country Life Guide to Marrakech: Where to shop, stay and eat

By Hetty Lintell -

'Attractive people doing attractive things in attractive places': Slim Aarons's photographs of Cortina d’Ampezzo resurface ahead of the Winter Olympics

By Florence Allen -

From Sicily to Sussex: What the Normans did for us

By Pamela Goodman

-

Food & Drink

View All Food & Drink-

The 'chef's table' is off the ick list

By Emma Hughes -

-

Sophia Money-Coutts: A snob's guide to supermarkets and what to do when there's no Waitrose

By Sophia Money-Coutts -

Patrick Galbraith: 'The idea that a bar in Norfolk selling vinho verde would make it through even one winter was about as likely as the Madonna herself reappearing by the old water pump'

By Patrick Galbraith -

Agromenes: The Food Waste Inspector is right to call out M&S, Waitrose and Lidl for throwing away food that is perfectly good to eat

By Agromenes -

Gill Meller's recipe for wholesome and flavourful cauliflower cheese gratin

By Gill Meller -

Forget haggis — the humble swede is the real hero of the Burns Night meal

By Douglas Chalmers -

Tom Parker Bowles talks tartiflette: 'This is not a dish worried about precision, elegance or nuance. It is all about beautiful ballast and you wouldn’t want it any other way'

By Tom Parker Bowles

-