-

There are more than 100 species of lemur living on the world's fourth-largest island — and they cannot be found anywhere else on Earth

By Rupert Uloth -

-

'It was the only design that spoke the same language as the house. It immediately felt right': An Oxfordshire home where house and garden work in perfect, asymmetrical harmony

By Tiffany Daneff -

A Caribbean home with its own nightclub, down the road from a perfect beach and a pre-Columbian castle

By Toby Keel -

Are you smarter than a 14-year-old? Country Life Quiz of the Day, February 27, 2026

By Country Life -

'My husband gave me a pendant full of melted snow from the top of Everest': Bridgerton's Julia Quinn on romantic gestures and her consuming passions

By Lotte Brundle -

It is the ‘year of the tiara’, but what’s a girl (or guy) to do if they don’t have an heirloom laying about?

By Felix Bischof -

It's alive! The UK producers embracing fermentation to make delicious products teeming with life

By Tom Howells

-

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

People & Places

-

-

The life of a BAFTA begins in an industrial estate in Braintree

-

The W1 set is up in arms about Liz Truss's roof terrace. But what is a members' club without one?

-

What have the Romans ever done for us? For one thing, taught us the art of seduction

-

‘I’m like: “Give me those tights, let me show you”: Ballet superstar Carlos Acosta’s consuming passions

-

Property

View all Property-

A Caribbean home with its own nightclub, down the road from a perfect beach and a pre-Columbian castle

By Toby Keel -

-

Alan Carr's new castle is 'a masterpiece of the baronial revival' with 17 bedrooms and its own miniature railway

By Toby Keel -

A house that's the epitome of the Yorkshire dream, in the heart of the county's 'Golden Triangle'

By Arabella Youens -

A country manor that's 18th century on the outside, 21st century on the inside

By Arabella Youens -

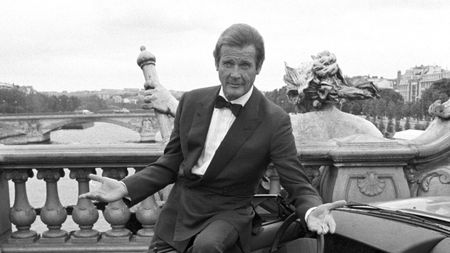

Sir Roger Moore's London pad is on the market

By Toby Keel -

'When it came up for sale again, it felt like destiny': Philip Mould on his first home in the country

By Julie Harding -

Best country houses for sale this week

By Country Life

-

Architecture

View all Architecture-

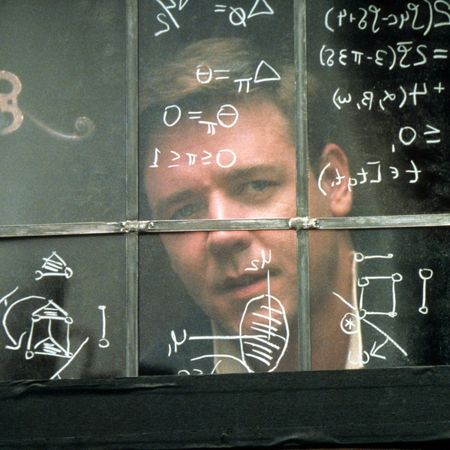

Why has everyone fallen under the spell of Wrotham Park — one of the largest private houses inside the M25

By Laura Kay -

-

Refurbishing the Palace of Westminster will be extremely expensive, but so too will be doing nothing

By Athena -

What binds the Queen Mother and Chicago's first department store? A lost Scottish castle that was blown to smithereens by the Territorial Army

By Melanie Bryan -

The only thing better than a stately home is a stately home in wooden miniature

By Will Hosie -

'I have never ceased talking of the beauty of Ampthill': The tale of one of Britain's best-loved country houses

By Jeremy Musson -

Les Espaces d'Abraxas: 'Building a Versailles for the people in Noisy-le-Grand'

By Tim Abrahams -

'A fantastic creation, with the magic of a strange, dreamed, longed-for world': Inside Schloss Charlottenhof, the Prussian royal family's exquisite sanctuary

By Aoife Caitríona Lau -

The magnificent London mansion that Country Life mourned when it was demolished to make room for the Dorchester Hotel

By Melanie Bryan

-

Our expert voices

Interiors

View All Interiors-

New designs and accessories to brighten every room

By Amelia Thorpe -

-

London Design Week: What to look out for at next month's unmissable interiors event

By Amelia Thorpe -

How do you add historic character back into a soulless room?

By Arabella Youens -

This clever interiors trick is the secret to creating multifunctional spaces — and it was integral to the design of many English country houses of the past

By Giles Kime -

'It was a complete wreck': Reclaiming a Hampshire coaching house from the earth

By Arabella Youens -

How do you add a dash of theatricality to a 1930s house? By taking inspiration from the legendary architect and set designer Oliver Messel

By Arabella Youens -

Are you a curator, a sympathiser or a conscientious objector? Take our Interiors Editor's quiz to discover your design DNA

By Giles Kime -

‘The pair drove to Belgium in their Mini and returned with the chair wrapped in duvets’: The mother-and-daughter duo that brought a converted Cotswolds barn back to life

By Arabella Youens

-

Gardens

View All Gardens-

'It was the only design that spoke the same language as the house. It immediately felt right': An Oxfordshire home where house and garden work in perfect, asymmetrical harmony

By Tiffany Daneff -

-

You don’t need to live in the countryside or have acres of space to start a cutting garden

By Amy Merrick -

Intrepid, enterprising, dedicated: The new generation of nursery owners creating the flowers we'll be enjoying for decades to come

By John Hoyland -

Alan Titchmarsh: Patience is in short supply today, but learning when to crack on and when to leave well alone will do your garden wonders

By Alan Titchmarsh -

Penns in the Rocks: The East Sussex garden created by Vita Sackville-West, with a little help from the huge boulders that stood here when dinosaurs walked the earth

By George Plumptre -

'I was utterly bewitched': The heartwarming success story of one of Britain's greatest rose-growers

By Charles Quest-Ritson

-

LIFE & STYLE

View All LIFE & STYLE-

-

It is the ‘year of the tiara’, but what’s a girl (or guy) to do if they don’t have an heirloom laying about?

By Felix Bischof -

1950 Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith: 'Much of the enjoyment is gained from the smoothness and precision with which the most minor details are fitted and work'

By James Fisher -

Do you own Britain’s naughtiest dog?

By Agnes Stamp -

'It seems as if hatboxes needn’t always contain hats: ideas can percolate there, too'

By Deborah Nicholls-Lee

-

THE COUNTRYSIDE

View All THE COUNTRYSIDE-

-

The winter Olympians of the natural world

By Rosie Paterson -

Feathers: Nature’s most exquisite miracle was fashioned for flight, fortitude and fantasy

By Charles Harris -

Britain's most widespread bird is also the most elusive — spotting it is one of ornithology’s great joys

By Mark Cocker

-

ART & CULTURE

View all ART & CULTURE-

-

'He was a French artist enamoured with light and colour, movement and lightness'

By James Fisher -

Write side up: The enduring influence of literature in art

By Carla Passino -

Pushing back against a culture of disposability: The enduring importance of craft

By Corinne Julius -

'He allowed lion and a tiger to prowl around the castle and, if an unfortunate servant was mauled, they were paid compensation': Exotic animals in art

By Michael Prodger

-

Travel

View All Travel-

There are more than 100 species of lemur living on the world's fourth-largest island — and they cannot be found anywhere else on Earth

By Rupert Uloth -

-

In the battle of travel tour operator versus AI, who will win?

By Rosie Paterson -

Hôtel du Couvent: This former convent on the French Riviera has rekindled the rules of luxury

By James Fisher -

This Hollywood star's home in the Canadian wilderness is now an exclusive-use lodge

By Rosie Paterson -

The real challenge facing Britain's grande dame seafront hotels

By Athena -

Couples are changing how they holiday — even on honeymoon

By Rosie Paterson

-

Food & Drink

View All Food & Drink-

It's alive! The UK producers embracing fermentation to make delicious products teeming with life

By Tom Howells -

-

‘French pastries all look amazing… but I wish more British bakers would look at what we used to have’: Richard Hart on the joys of jammy dodgers and iced buns

By Oliver Berry -

Where's the rum gone? How the temperance movement took on the Royal Navy

By Henry Jeffreys -

Tom Parker Bowles: 'There is no dish more lusty and full blooded than boeuf à la Bourguignonne'

By Tom Parker Bowles -

The 'chef's table' is off the ick list

By Emma Hughes -

Sophia Money-Coutts: A snob's guide to supermarkets and what to do when there's no Waitrose

By Sophia Money-Coutts -

Patrick Galbraith: 'The idea that a bar in Norfolk selling vinho verde would make it through even one winter was about as likely as the Madonna herself reappearing by the old water pump'

By Patrick Galbraith

-