-

To celebrate 100 years of the Rolls-Royce Phantom, we took it back to its roots

By Matthew MacConnell

-

-

The 12 dogs of Christmas

By Florence Allen

-

18 beautiful house for sale, from home counties dream to a private island with its own castle, as seen in Country Life

By Toby Keel

-

What the Country Life team are asking Father Christmas for this year

By Rosie Paterson

-

A fate worse than demolition? The desecration of the original Bank of England, one of Georgian architecture's great masterpieces

By Clive Aslet

-

On the edge of the world, beyond the mainland's most remote village, this self-sufficient dream home is for sale at £395,000

By Toby Keel

-

East London's salmon smokehouse full of secrets

By Tom Howells

-

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

People & Places

-

-

I was Jeremy Hunt’s main political adviser and helped put together multiple Autumn Statements and Budgets. This is what I think Rachel Reeves’s Budget means for the countryside

-

What on earth is the person who comes up with Annabels's otherworldly facade displays on? London's most magical Christmas shop displays

-

Who buys flowers in the middle of the night? Boris Johnson, panicked brides, drunk people and London’s wealthiest inhabitants

-

All fired up: 12 of our favourite chimneys, from grand architectural statements to modest brick stacks, as seen in Country Life

-

Property

View all Property-

18 beautiful house for sale, from home counties dream to a private island with its own castle, as seen in Country Life

By Toby Keel

-

-

On the edge of the world, beyond the mainland's most remote village, this self-sufficient dream home is for sale at £395,000

By Toby Keel

-

The dream ski chalet for sale: Be the envy of the entire Trois Vallées

By James Fisher

-

'We’re in the golden era of family life': The rather lovely accidental up-side of the wildly spiralling cost of housing

By Toby Keel

-

A picture-perfect home that's so Country Life it even has an Aga in the gym

By Penny Churchill

-

Property with potential: Renovation projects for sale, starting from just £170,000

By Toby Keel

-

Best country houses for sale this week

By Country Life

-

Our expert voices

Interiors

View All Interiors-

John Goodall: Restoration is 'an act of recycling', but we need a system that encourages it

By John Goodall

-

-

Making space in a Georgian terraced Chelsea cottage

By Arabella Youens

-

Moths and memories of the Russian Revolution: Why it's worth saving that tired old rug

By Catriona Gray

-

How one family went about creating a welcoming kitchen in one of England's neo-Palladian houses

By Arabella Youens

-

How do you make a 300-year-old Baronial castle fit for modern-day living?

By Arabella Youens

-

Oh, my gourd, it’s Hallowe’en: How best to decorate your home with pumpkins, squashes and more

By Debora Robertson

-

At the Snowdon Summer School, the future of design lies in the traditions of the past

By Giles Kime

-

A derelict school turned into a gorgeous home with 'an interior of harmony and visual éclat'

By John Martin Robinson

-

LIFE & STYLE

View All LIFE & STYLE-

-

To celebrate 100 years of the Rolls-Royce Phantom, we took it back to its roots

By Matthew MacConnell

-

What the Country Life team are asking Father Christmas for this year

By Rosie Paterson

-

‘I have an obsession with having a good time’: Fred Siriex on his newfound love of gardening, moving to the UK and his consuming passions

By Lotte Brundle

-

‘Not to move at all is deeply slutty, in the old-fashioned sense of the word’: A snob’s guide to surviving Christmas Day

By Sophia Money-Coutts

-

COUNTRYSIDE

View All THE COUNTRYSIDE-

-

Is December the best month for bird watching? Exploring the underrated avian delights of a British winter

By Country Life

-

'A teaspoon of living soil contains more creatures than there are people in existence': Unearthing the dirt's vital role in our future on World Soil Day

By Sarah Langford

-

I was Jeremy Hunt’s main political adviser and helped put together multiple Autumn Statements and Budgets. This is what I think Rachel Reeves’s Budget means for the countryside

By Adam Smith

-

Gardens

View All Gardens-

How to create spectacular arrangements for your Christmas table

By Amy Merrick

-

-

There are a billion microbes in a teaspoon of soil. Leaving the leaves to Nature feeds and nourishes them

By Isabel Bannerman

-

What trees taught me about perfect planting — Alan Titchmarsh

By Alan Titchmarsh

-

When it comes to making the perfect garden tool, the past has all the answers

By Mary Keen

-

Exclusive: The King's remarkable resurrection of the gardens and parkland at Sandringham

By Charles Quest-Ritson

-

'A dream of Nirvana... almost too good to be true': The sweet peas of Easton Walled Gardens, and how you can replicate their success at home

By Ursula Cholmeley

-

ART & CULTURE

View all ART & CULTURE-

-

Power, prestige and passion: Where to see more than 100 of the world’s best dynastic jewels

By Amy Serafin

-

Is the British Museum's attempt to save a Tudor-era pendant with links to Henry VIII proof that the institution is on the up?

By Athena

-

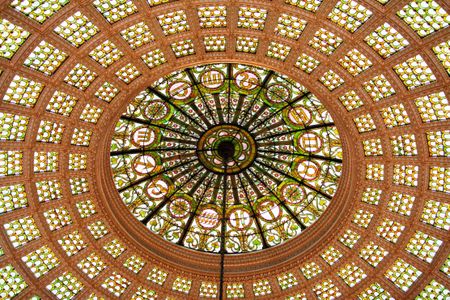

'Gems of enflamed transparencies, of bottomless blues, of congealed opals': Why glass was perfect for the elemental experimentalism of Art Nouveau

By Matthew Dennison

-

Who won the rivalry between Turner and Constable? It was us, the public

By Carla Passino

-

Travel

View All Travel-

'The ugliness and craziness is a part of its charm': The Country Life guide to Bangkok

By Luke Abrahams

-

-

The Surrey hotel review: The new kid on New York's Upper East Side

By Rosie Paterson

-

Whodunnit? Le Bristol hotel in Paris already has a resident Birman cat — now it has its own Cluedo game too

By Rosie Paterson

-

Ardbeg House review: Concept design is a tricky business, but this Scottish whisky distillery-turned-hotel proves that it can be done to great effect

By Steven King

-

'The night smells like engine oil… and money': Singapore’s glittering night race paved the way for a new era of city-centre Grands Prix

By Natasha Bird

-

Storrs Hall: A glimpse of what a trip to Lake Windermere ought to be

By Toby Keel

-

Food & Drink

View All Food & Drink-

East London's salmon smokehouse full of secrets

By Tom Howells

-

-

Four festive recipes from the Country Life Archive that have (thankfully) fallen out of favour

By Melanie Bryan

-

Country Life's luxury editor's Christmas gift ideas for foodies, from traditional hampers to nifty kitchen gadgets

By Amie Elizabeth White

-

‘Calf’s brains have a bland, gentle richness that soothes and cossets': Tom Parker Bowles on the joys of eating offal

By Tom Parker Bowles

-

A paprika-spiked goulash recipe to keep you warm as the nights draw in

By Tom Parker Bowles

-

What is everyone talking about this week: Is the Golden Age of fine dining over?

By Will Hosie

-

No more froths, no more foams, no more tweezers. Classic dining is making a comeback. Thank god

By David Ellis

-