-

Best country houses for sale this week

By Country Life

-

-

Sophia Money-Coutts: Is it ever okay to throw your dog a birthday party?

By Sophia Money-Coutts

-

A 500-acre estate that spent 11 centuries in the same family, for sale for only the second time in its history

By Penny Churchill

-

‘They remain, really, the property of all of those who love them, know them, and tell them. They are our stories, the inheritance of the people of Scotland’: The Anthology of Scottish Folk Tales

By Patrick Galbraith

-

The English church that looks like a Van Gogh fever dream: Country Life Quiz of the Day, July 8, 2025

By Country Life

-

What it's like to come face-to-face with a great white shark, with Dan Abbott of Netflix's All The Sharks

By Toby Keel

-

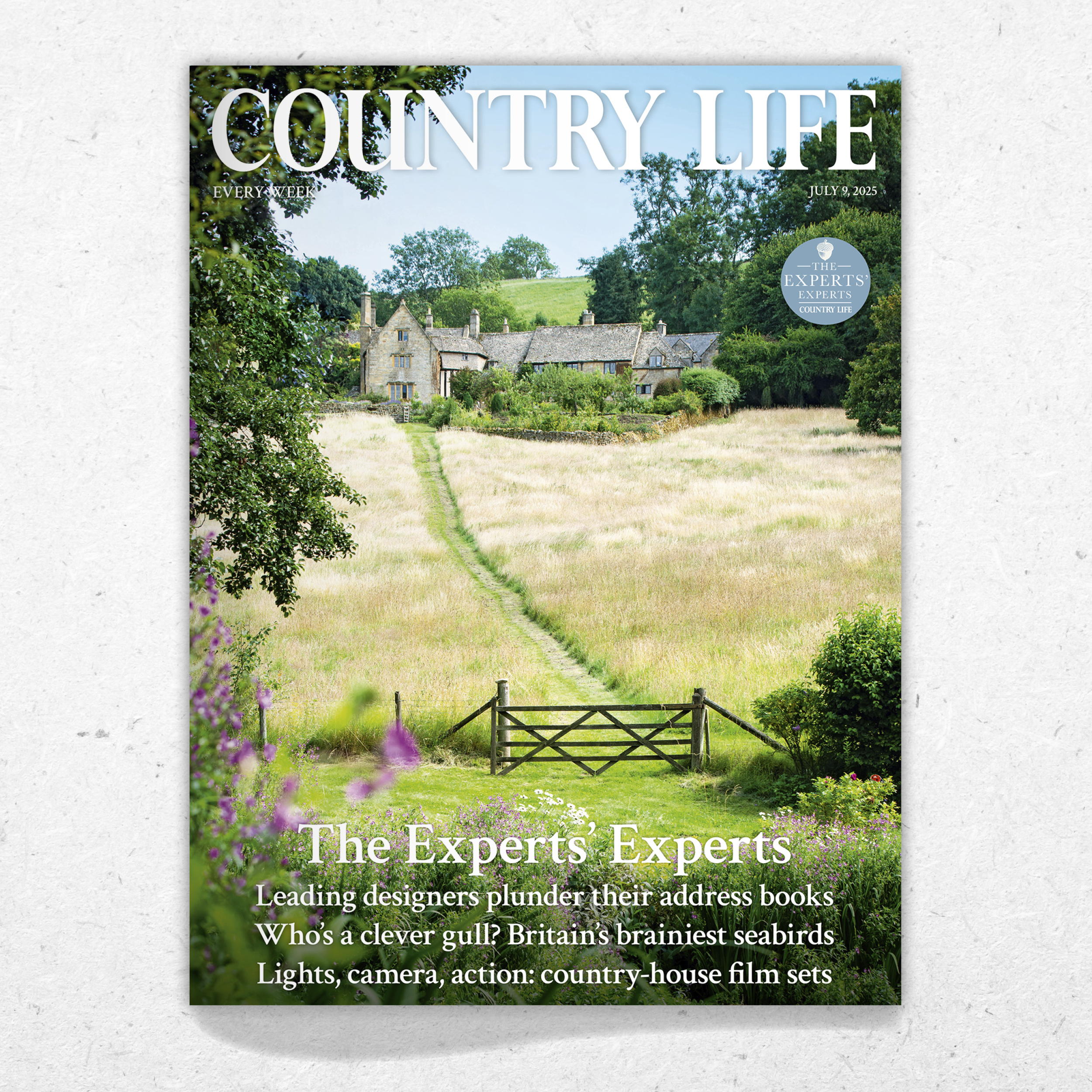

This week's issue of Country Life — and how to subscribe or get your copy

By Country Life

-

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

People & Places

-

-

Why society needs snobs to tell us that 'actually, we've got this terribly wrong'

-

For every new stone mason, seven retire: St Paul's plan to save heritage crafts — and itself in the process

-

Richard Mille: The man who went from carving watches out of soap to making timepieces for Rafael Nadal and Lando Norris — and built a £1bn business in the process

-

The Manner review: This New York hotel is bringing the 1970s back to SoHo, one colour at a time

-

Property

View all Property-

Best country houses for sale this week

By Country Life

-

-

A 500-acre estate that spent 11 centuries in the same family, for sale for only the second time in its history

By Penny Churchill

-

'The city has always held an important creative space within our design studio': A luxury townhouse in Tokyo, courtesy of Aston Martin

By James Fisher

-

The Mediterranean Magic of Malta

By Holly Kirkwood

-

Four country houses with their own tennis courts, as seen in Country Life

By Annunciata Elwes

-

The majestic New Forest estate formerly owned by a billionaire adventurer — famous for driving 'the world's fastest kettle' — has come up for sale

By Anna White

-

A Hampshire Manor for sale that dates back to the days of Alfred the Great, with the most beautiful staircase we've seen in years

By Lotte Brundle

-

Our expert voices

Interiors

View All Interiors-

I've seen the light: How a dark and gloomy kitchen in the Scottish Borders was reconfigured for 21st century living

By Arabella Youens

-

-

'Comfortable, cosseting and far from the madding crowd': The recently refurbished Cornish cottage that proves Victorian decor is making a comeback

By Giles Kime

-

18 inspiring ideas to help you make the most of meals in the garden this summer

By Amelia Thorpe

-

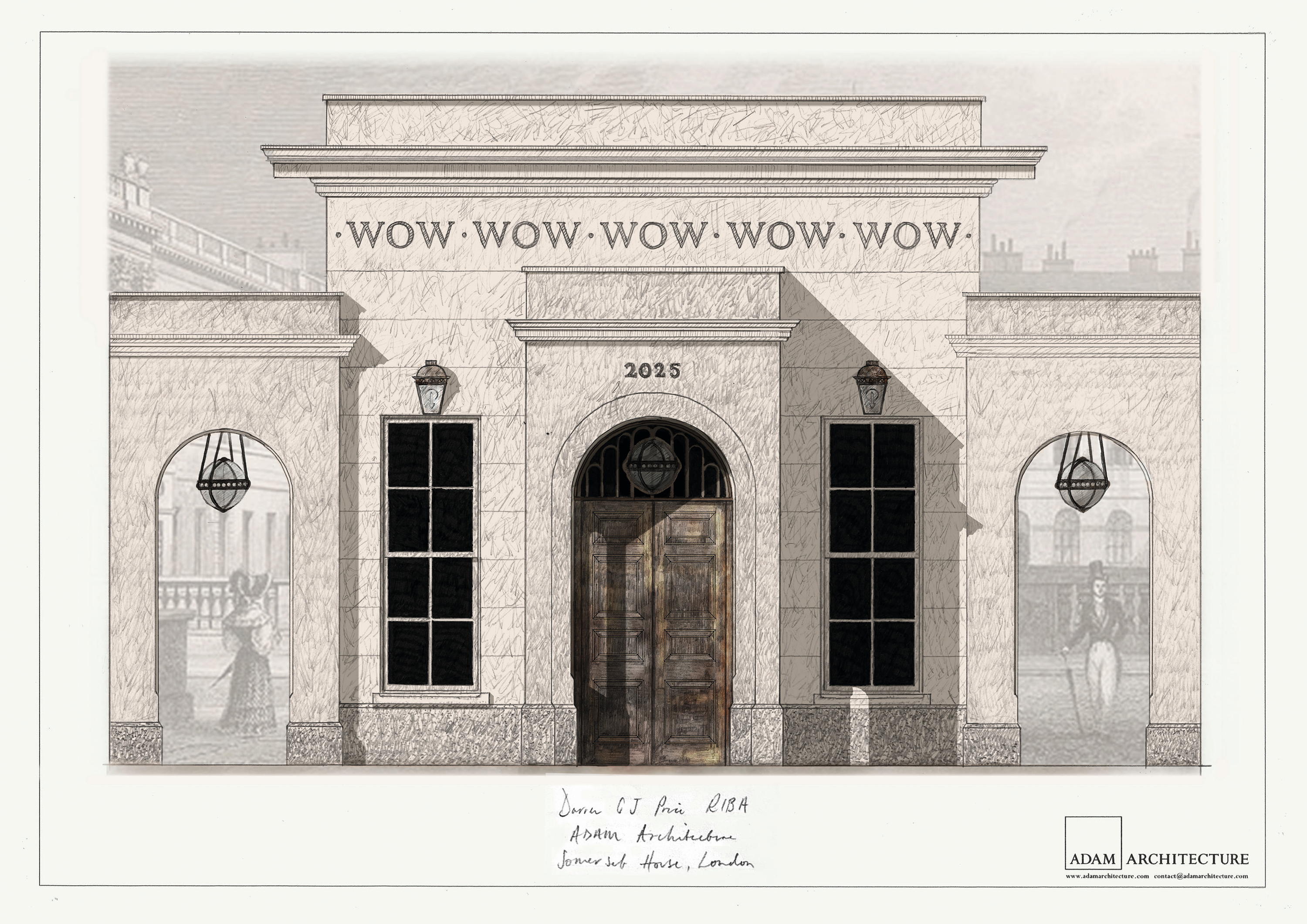

'These aren't just rooms. They are spaces configured with enormous cunning, artfully combining beauty with functionality': Giles Kime on the wonders of WOW!house 2025

By Giles Kime

-

How the deep-lustre of copper brings period glamour to this kitchen

By Arabella Youens

-

The beauty’s in the detail: How English stone specialist Artorius Faber helped to bring Country Life's Chelsea stand to life

By Artorius Faber

SPONSORED -

A feast of ideas: What to expect at WOW!house 2025

By Amelia Thorpe

-

Curious Questions: Where did the viral Instagram Shaker kitchen come from — and how is it linked to Quakerism?

By Alexandra Goss

-

LIFE & STYLE

View All LIFE & STYLE-

-

Tuning in with the past: Monk music will ring out for the first time since the Dissolution after medieval manuscript is rediscovered

By Annunciata Elwes

-

Water you're waiting for? Britain's best heritage lidos were built to save swimmers from polluted seas full of potato peelings, oil and coal — and they're still in action today

By Kathryn Ferry

-

‘There is probably no sport in the world which is so misunderstood’: 75 years of Formula 1 according to the Country Life archive

By Rosie Paterson

-

West London's spent the last two decades as the laughing stock of the style set — here's how it got its groove back

By Will Hosie

-

COUNTRYSIDE

View All THE COUNTRYSIDE-

-

What it's like to come face-to-face with a great white shark, with Dan Abbott of Netflix's All The Sharks

By Toby Keel

-

The life that thrives among the dead: How wildlife finds a home in the graveyards and churchyards of Britain

By Laura Parker

-

Peregrine falcons went to the edge of extinction in the 1960s — today, there are more of them than at any time since the Middle Ages

By Mark Cocker

-

Gardens

View All Gardens-

Alan Titchmarsh: My garden is as pretty as I've ever known it, thanks to an idea I've rediscovered after 50 years

By Alan Titchmarsh

-

-

The Hollywood garden designers who turned their hand to a magical corner of Somerset

By Caroline Donald

-

Sarah Raven: The flowers I have that are flourishing superbly, despite the battering heat

By Sarah Raven

-

The 'Rose Labyrinth' of Coughton Court, where 200 varieties come together in this world-renowned garden in Warwickshire

By Val Bourne

-

'None of this would be here had the tithe barn not burned down that night’: How the terrifying destruction of a medieval landmark sparked the creation of the magnificent gardens of Bledlow Manor

By Tiffany Daneff

-

'The whole house shook. Everything was white. For four months, it felt as if we were on Mars': The story behind one of Hampshire's most breathtaking gardens

By Non Morris

-

ART & CULTURE

View all ART & CULTURE-

-

‘They remain, really, the property of all of those who love them, know them, and tell them. They are our stories, the inheritance of the people of Scotland’: The Anthology of Scottish Folk Tales

By Patrick Galbraith

-

Canine muses: Lucian Freud's etchings of Pluto the whippet are among his most popular and expensive work

By Agnes Stamp

-

‘Reactions to the French in the 1870s varied from outrage to curious interest’: Impressionism's painstaking ten year journey to be taken seriously by the Brits

By Caroline Bulger

-

Canine muses: The English bull terrier who helped transform her owner from 'a photographer into an artist'

By Agnes Stamp

-

Travel

View All Travel-

‘‘In the silence, it is the most perfect blue I have ever seen. If my goggles weren’t already overflowing with water I might even weep’: Learning to freedive on the sparkling French Riviera with a five-time World Champion

By Chris Cotonou

-

-

'Champagne is not simply a place, it’s a symbol of excellence': How a quiet rural region shrugged off war, famine and pestilence to become the home of the ultimate luxury tipple

By Lotte Brundle

-

Sophia Money-Coutts: When is the right moment to put your seat back on a plane?

By Sophia Money-Coutts

-

‘Whatever do you do up there?’ enquire certain English infidels. The answer? ‘Lady, if ya gotta ask, ya’ll never know’: David Profumo's piece of heaven in Highland Perthshire

By David Profumo

-

Game, set, match: 12 of the world’s most beautiful tennis courts beyond SW19

By Rosie Paterson

-

'Meat, ale and guns — what else do you need, bar glorious scenery?': William Sitwell on the Brendon Hills, West Somerset

By William Sitwell

-

Food & Drink

View All Food & Drink-

The last miracle of St Boswell? How a Scottish potato field became the world's least-likely producer of sparkling wine

By Lotte Brundle

-

-

How to make The Connaught Bar's legendary martini — and a few others

By Rosie Paterson

-

Gill Meller's tomato, egg, bread and herb big-hearted summer salad

By Gill Meller

-

Sophia Money-Coutts: Why clinking glasses and saying ‘Cheers!’ is a tiny bit embarrassing

By Sophia Money-Coutts

-

What do an order of Catholic priests and actor Hugh Bonneville have in common? They helped this West Sussex sparkling wine triumph over multiple French Champagne houses

By Lotte Brundle

-

11 golden rules for making a perfect cup of tea

By Jonathon Jones

-

How to make Eton mess strawberry blondies

By Melanie Johnson

-