-

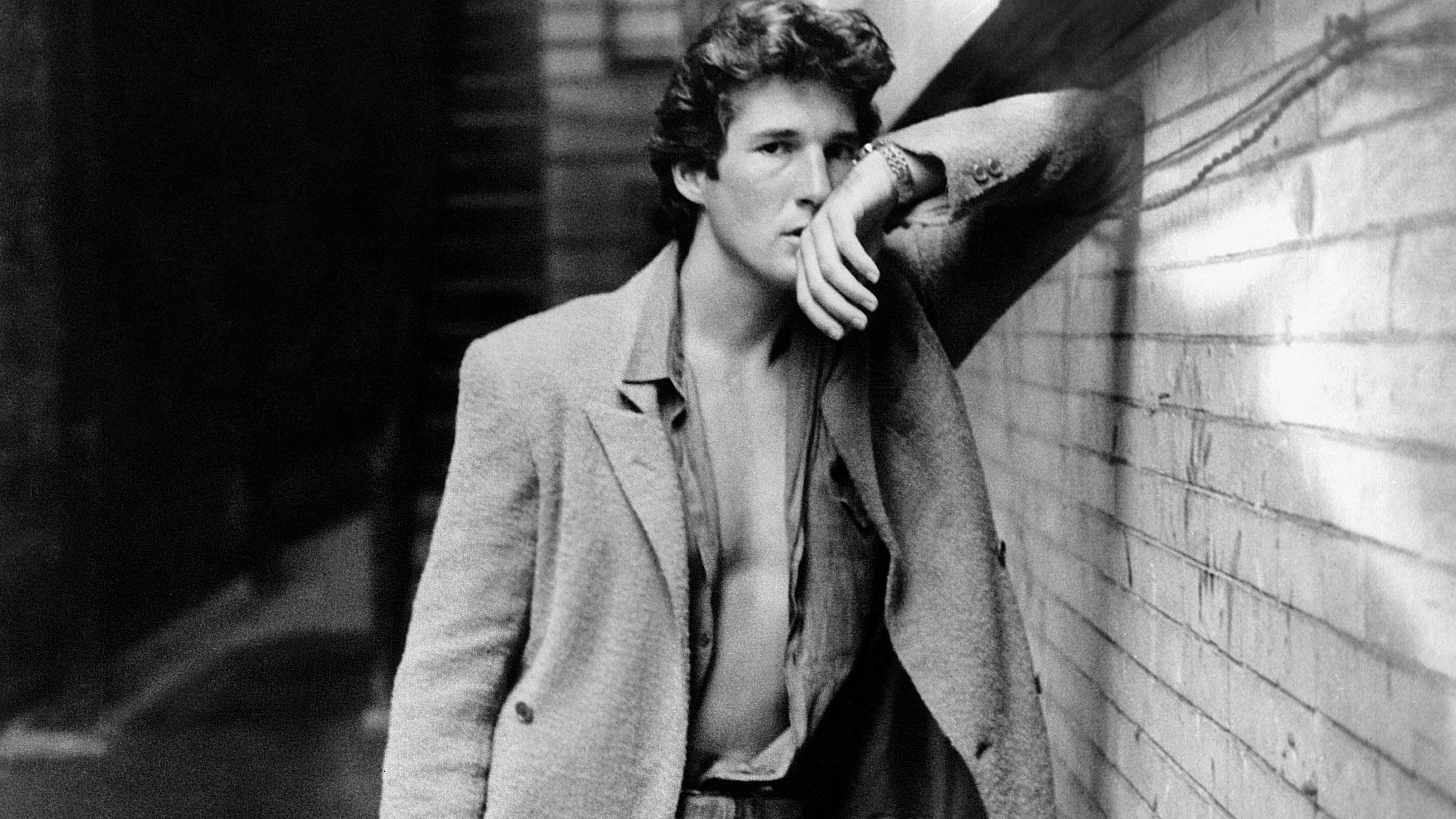

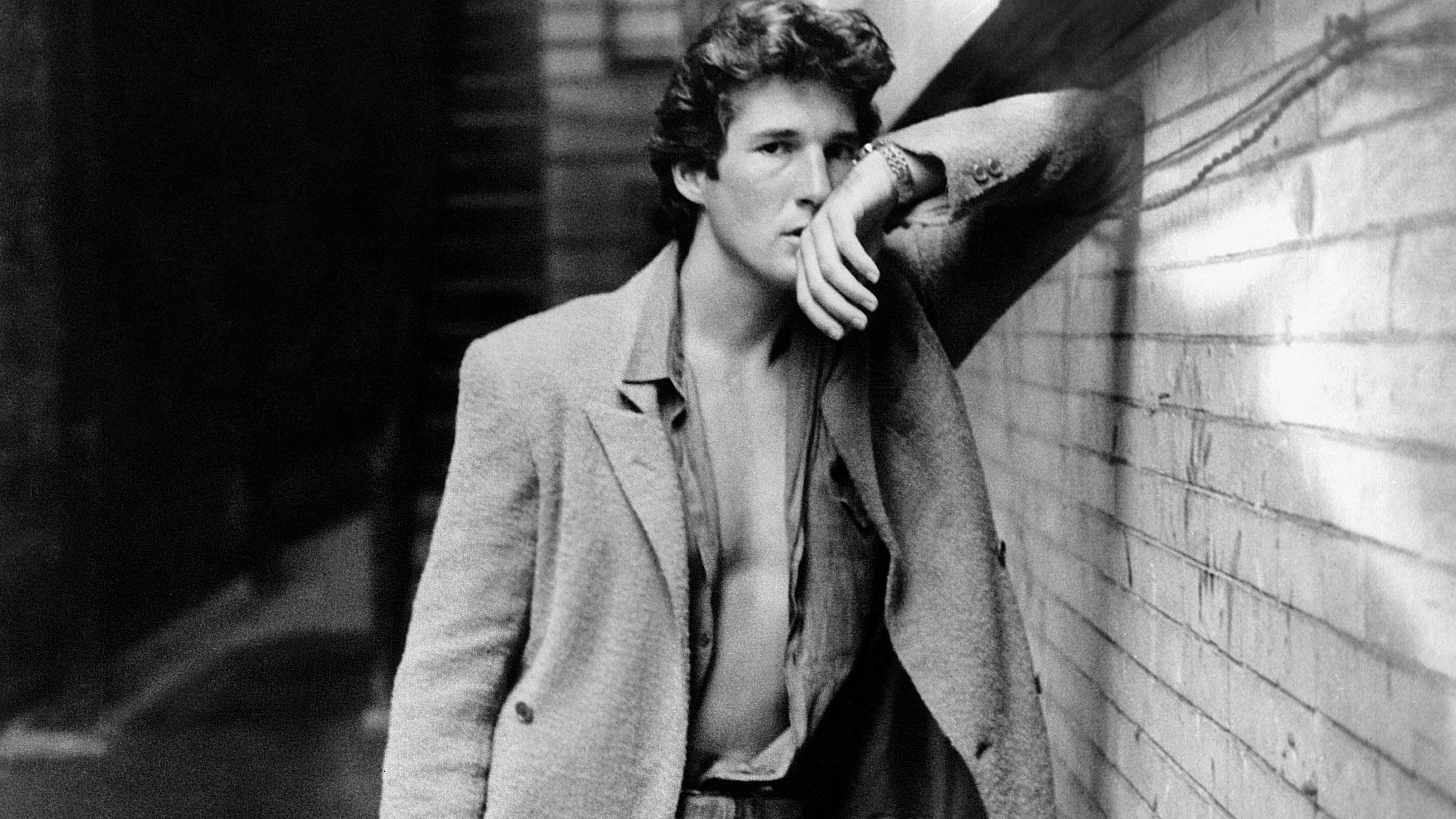

What do 19th century rowers, Queen Victoria and Giorgio Armani all have in common? They helped to popularise the world's most versatile jacket — the blazer

By Harry Pearson

-

-

Best country houses for sale this week

By Country Life

-

Sophia Money-Coutts: When is the right moment to put your seat back on a plane?

By Sophia Money-Coutts

-

Where Venice once ruled: The roving Venetians left handsome imprints across the Greek world, from its religion to its rambling villas

By Matthew Dennison

-

The real Bear Grylls: Country Life Quiz of the Day, July 2, 2025

By Country Life

-

‘Whatever do you do up there?’ enquire certain English infidels. The answer? ‘Lady, if ya gotta ask, ya’ll never know’: David Profumo's piece of heaven in Highland Perthshire

By David Profumo

-

This week's issue of Country Life — and how to subscribe or get your copy

By Country Life

-

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

People & Places

-

-

‘It has been destroyed beyond repair, not by the effect of gunfire, but by a deliberate act of vandalism’: Britain’s long lost great houses that live on only inside the Country Life archive

-

Henry Holland's consuming passions: 'I started my career as the fashion editor of Smash Hits magazine and I am still a pop tart at heart!'

-

The extraordinary Exe Estuary, by the Earl whose family have lived here for 700 years

-

‘There are moments of formal dressing where one is humbled by the rules of it all’: A New Yorker tackles Royal Ascot for the first time

-

Property

View all Property-

Best country houses for sale this week

By Country Life

-

-

Where Venice once ruled: The roving Venetians left handsome imprints across the Greek world, from its religion to its rambling villas

By Matthew Dennison

-

A delightful 16th century home with some of Kent's most beautiful gardens has come on to the market

By Penny Churchill

-

A pristine Scottish island for sale at the price of a garage in Fulham

By Toby Keel

-

18 beautiful homes, from charming cottages to a Highland mansion with unbeatable views, as seen in Country Life

By Toby Keel

-

The gorgeous Somerset home of the designer behind one of Glastonbury's chicest spots

By Toby Keel

-

A 600-year-old National Trust property that you can call home

By Penny Churchill

-

Our expert voices

Interiors

View All Interiors-

'Comfortable, cosseting and far from the madding crowd': The recently refurbished Cornish cottage that proves Victorian decor is making a comeback

By Giles Kime

-

-

18 inspiring ideas to help you make the most of meals in the garden this summer

By Amelia Thorpe

-

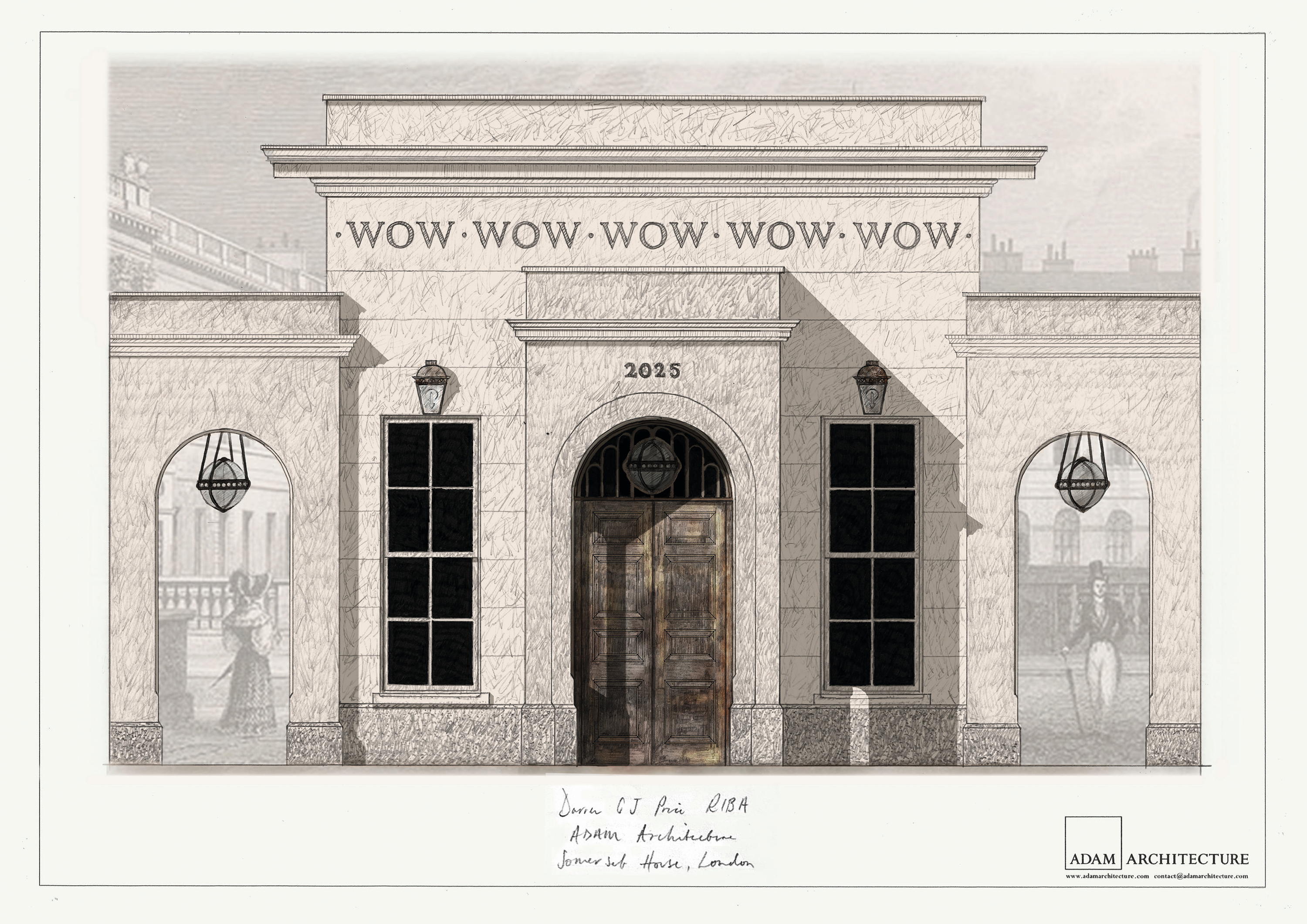

'These aren't just rooms. They are spaces configured with enormous cunning, artfully combining beauty with functionality': Giles Kime on the wonders of WOW!house 2025

By Giles Kime

-

How the deep-lustre of copper brings period glamour to this kitchen

By Arabella Youens

-

The beauty’s in the detail: How English stone specialist Artorius Faber helped to bring Country Life's Chelsea stand to life

By Artorius Faber

SPONSORED -

A feast of ideas: What to expect at WOW!house 2025

By Amelia Thorpe

-

Curious Questions: Where did the viral Instagram Shaker kitchen come from — and how is it linked to Quakerism?

By Alexandra Goss

-

The designer's room: How rare, 19th-century wallpaper was repurposed inside a Grade I-listed apartment complex on London's Piccadilly

By Arabella Youens

-

LIFE & STYLE

View All LIFE & STYLE-

-

What do 19th century rowers, Queen Victoria and Giorgio Armani all have in common? They helped to popularise the world's most versatile jacket — the blazer

By Harry Pearson

-

‘I get all twitchy when I see people wearing something that really doesn’t belong’: A watch for every summer occasion

By Chris Hall

-

Coco's crush: Chanel's century-long love affair with Britain and its men

By Amie Elizabeth White

-

Critics be damned, Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral gets Grade I status on advice from Historic England

By Annunciata Elwes

-

COUNTRYSIDE

View All THE COUNTRYSIDE-

-

I lichen the look of you: A rare lichen-covered fingerpost that's been frozen in time and donated to the Natural History Museum

By Annunciata Elwes

-

Marcus Janssen: The man behind Schöffel on Chelsea Lifejackets, bagging a 'MacNab' and recognising the best of the British countryside

By James Fisher

-

Beyond Stonehenge: The ancient moorland megaliths and grand stone rings that you can enjoy without the tourist hordes

By Tom Howells

-

Gardens

View All Gardens-

Sarah Raven: The flowers I have that are flourishing superbly, despite the battering heat

By Sarah Raven

-

-

The 'Rose Labyrinth' of Coughton Court, where 200 varieties come together in this world-renowned garden in Warwickshire

By Val Bourne

-

'None of this would be here had the tithe barn not burned down that night’: How the terrifying destruction of a medieval landmark sparked the creation of the magnificent gardens of Bledlow Manor

By Tiffany Daneff

-

'The whole house shook. Everything was white. For four months, it felt as if we were on Mars': The story behind one of Hampshire's most breathtaking gardens

By Non Morris

-

Myddleton House: The place that 'will help you learn what true gardening is' is open to everyone, and just 30 minutes from central London

By Isabel Bannerman

-

'Victorian magnificence skilfully simplified and distilled': A peek at the restoration of Somerleyton Hall gardens

By Tilly Ware

-

ART & CULTURE

View all ART & CULTURE-

-

Canine muses: The English bull terrier who helped transform her owner from 'a photographer into an artist'

By Agnes Stamp

-

Richard Rogers: 'Talking Buildings' is a fitting testament to the elegance of utility

By James Fisher

-

‘The perfect hostess, he called her’: A five minute guide to Virgina Woolf’s ‘Mrs Dalloway’

By Lotte Brundle

-

This obscure and unloved picture that turned out to be Turner's first oil painting — and it's about to sell for 500 times what it last cost

By Toby Keel

-

Travel

View All Travel-

Sophia Money-Coutts: When is the right moment to put your seat back on a plane?

By Sophia Money-Coutts

-

-

‘Whatever do you do up there?’ enquire certain English infidels. The answer? ‘Lady, if ya gotta ask, ya’ll never know’: David Profumo's piece of heaven in Highland Perthshire

By David Profumo

-

Game, set, match: 12 of the world’s most beautiful tennis courts beyond SW19

By Rosie Paterson

-

'Meat, ale and guns — what else do you need, bar glorious scenery?': William Sitwell on the Brendon Hills, West Somerset

By William Sitwell

-

'Fences have blocked wildlife corridors, causing the wildebeest migration to collapse from 140,000 individuals to fewer than 15,000': Is the opening of the Ritz-Carlton in Kenya’s Masai Mara National Reserve a cause for celebration or concern?

By Lisa Johnson

-

The pristine and unspoilt English county that 'has all the ingredients of perfection'

By Viscount Ridley

-

Food & Drink

View All Food & Drink-

How to make The Connaught Bar's legendary martini — and a few others

By Rosie Paterson

-

-

Gill Meller's tomato, egg, bread and herb big-hearted summer salad

By Gill Meller

-

Sophia Money-Coutts: Why clinking glasses and saying ‘Cheers!’ is a tiny bit embarrassing

By Sophia Money-Coutts

-

What do an order of Catholic priests and actor Hugh Bonneville have in common? They helped this West Sussex sparkling wine triumph over multiple French Champagne houses

By Lotte Brundle

-

11 golden rules for making a perfect cup of tea

By Jonathon Jones

-

How to make Eton mess strawberry blondies

By Melanie Johnson

-

The era of the £50 burger and chips is here — and it's a revelation

By Will Hosie

-