-

Zero XE: The mountain bike on steroids that zips silently around the countryside

By Patrick Galbraith

-

-

The smartest dog breed in the world — loved by Robert Burns and Queen Victoria

By Florence Allen

-

Five magical homes for sale, from an 18,000sq ft mansion in Devon to a 1960s-period piece right on the waterfront in Cornwall

By Toby Keel

-

Hello Kitty, the FBI and the exclusive island of Nantucket: Weird and wonderful tartans, and where to find them

By Lotte Brundle

-

A golden-stone manor that's just about as perfect a Cotswolds home as you could wish for

By Toby Keel

-

‘I thought I was going to be sick. I was very nervous about MasterChef’: Monica Galetti’s consuming passions

By Lotte Brundle

-

'We're not looking to make two dodos. We're looking to make thousands': Bringing the world's most famous bird back to life

By Emma Hughes

-

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

People & Places

-

-

Six things that Britain should be proud of, from world-class restaurants and Championship-winning cars to the countryside

-

Gavin Plumley: Shakespeare’s country isn’t Stratford-upon-Avon, it’s the quiet and beautiful Herefordshire countryside where Hamnet was filmed

-

How an eco-friendly interior designer transformed a former milking parlour into a multi-purpose space in the middle of the Pandemic

-

The 400-year-old floors perfectly preserved in the house that inspired Charles Dickens to create Miss Havisham's mansion

-

Property

View all Property-

Five magical homes for sale, from an 18,000sq ft mansion in Devon to a 1960s-period piece right on the waterfront in Cornwall

By Toby Keel

-

-

A golden-stone manor that's just about as perfect a Cotswolds home as you could wish for

By Toby Keel

-

An 'architectural masterpiece' on New York's Fifth Avenue — and Ralph Lauren could be your neighbour

By Rosie Paterson

-

A 'wildly romantic' castle that once hosted royalty and supermodels, saved from ruin and ready for a new family to make it their home

By Annabel Dixon

-

'Like valuing an antique': The fine art of balancing provenance, history, and size when pricing Britain's rarest homes

By Lucy Denton

-

John Constable's old school is for sale, and it's now a 500-year-old house in the wonkiest village in Britain

By Julie Harding

-

Best country houses for sale this week

By Country Life

-

Our expert voices

Interiors

View All Interiors-

How do you add a dash of theatricality to a 1930s house? By taking inspiration from the legendary architect and set designer Oliver Messel

By Arabella Youens

-

-

Are you a curator, a sympathiser or a conscientious objector? Take our Interiors Editor's quiz to discover your design DNA

By Giles Kime

-

‘The pair drove to Belgium in their Mini and returned with the chair wrapped in duvets’: The mother-and-daughter duo that brought a converted Cotswolds barn back to life

By Arabella Youens

-

'You should need little reminding that the 1980s are back': Country Life's interior-design predictions for 2026

By Giles Kime

-

How an eco-friendly interior designer transformed a former milking parlour into a multi-purpose space in the middle of the Pandemic

By Grace McCloud

-

How Britain’s biggest and best country houses are decking the halls (and façades) for Christmas

By Bella Fulford

-

Giles Kime: Cushions, rugs, upholstered stools and sofa blankets are the ingredients of a pleasing new trend

By Giles Kime

-

John Goodall: Restoration is 'an act of recycling', but we need a system that encourages it

By John Goodall

-

LIFE & STYLE

View All LIFE & STYLE-

-

Hello Kitty, the FBI and the exclusive island of Nantucket: Weird and wonderful tartans, and where to find them

By Lotte Brundle

-

‘I thought I was going to be sick. I was very nervous about MasterChef’: Monica Galetti’s consuming passions

By Lotte Brundle

-

Come rain or shine: Burberry’s Gabardine Capsule collection celebrates the art of dressing for Britain’s changeable skies

By Rosie Paterson

-

Posh people do well on I'm A Celebrity... Get Me Out of Here! because they survived boarding school: Sophia Money-Coutt's snob's guide to reality television

By Sophia Money-Coutts

-

COUNTRYSIDE

View All THE COUNTRYSIDE-

-

The evergreen appeal of winter tree planting

By Country Life

-

Small but mighty: How can you not love the little owl?

By Mark Cocker

-

From woodland to Westminster: Can the felling of ancient oak trees be an act of cultural service?

By Katharine Freeland

-

Gardens

View All Gardens-

The gardeners' gardens: Alan Titchmarsh, Mary Keen, Clive Nichols and more on the places they have on their 2026 hitlists

By Tiffany Daneff

-

-

Beautiful, rewarding, unpronounceable: Chaenomeles, the spectacular shrub that grows happily in gardens where azaleas will never bloom

By Charles Quest-Ritson

-

What is everyone talking about this week: Rewilding starts in your own back garden — even in the city

By Will Hosie

-

English country gardens once dotted the French Riviera. Now the last of them is about to slip away forever

By Charles Quest-Ritson

-

Three plants to grow in 2026 that are as delicious as they are pretty, from Siberian chives to 'Turkish warty cabbage'

By Mark Diacono

-

Seeing the centuries old specimens of Carl Linnaeus in a new light

By Christopher Stocks

-

ART & CULTURE

View all ART & CULTURE-

-

Eileen Soper: The 'schoolgirl among the masters' with paintings in millions of homes, even yours

By Ian Morton

-

A mesmerising portrait in the eerie country house that inspired Charlotte Brontë to write 'Jane Eyre'

By John Goodall

-

Wealthy Boomers collected blue-chip paintings. Gen Z is opting for collectibles. Who will come up trumps?

By Owen Holmes

-

The 'micro mosaic' at Holkham Hall that uses a fascinating, unusual technique pioneered by the Vatican

By John Goodall

-

Travel

View All Travel-

Sopwell House hotel review: For a spa trip, look no further

By Lotte Brundle

-

-

The Seaside Boarding House review: The cosy gourmet getaway on Dorset’s Jurassic Coast with a proper sense of place

By Emma Hughes

-

Above the clouds to beat the crowds: Where to stay in Wales if you want to conquer the 'other' Snowdon

By Tiffany Daneff

-

Inside the 19th century château in St Tropez where hotel guests are ferried to the beach in Rolls-Royces and season four of The White Lotus is about to start filming

By Rosie Paterson

-

Revelstoke is the heli-skiing capital of the world, where legendary powder, lethal lines and famous names collide

By Adam Hay-Nicholls

-

This new hotel medi-spa in Morocco has got tongues wagging for all the right reasons — and it’s nearly as big as The White House

By Jennifer George

-

Food & Drink

View All Food & Drink-

Forget haggis — the humble swede is the real hero of the Burns Night meal

By Douglas Chalmers

-

-

Tom Parker Bowles talks tartiflette: 'This is not a dish worried about precision, elegance or nuance. It is all about beautiful ballast and you wouldn’t want it any other way'

By Tom Parker Bowles

-

For Hairy Biker Si King, the secret ingredients will always be hard work and community

By Molly Pepper Steemson

-

The enduring allure of menus from ancient civilisations to modern day, via the revolutionary France

By John F. Mueller

-

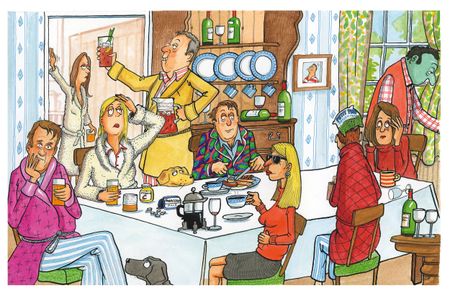

The 12 types of hangover, from 'Backwards Binoculars' to 'Titanic', and how to cure them all

By Olly Smith

-

'We begin making in May and start packing and despatching in November — it’s carnage': How the Cotswolds' favourite cake-makers get ready for Christmas

By Jane Wheatley

-

Tim Wilson of The Ginger Pig on the perfect Christmas ham

By Jane Wheatley

-