-

What binds the Queen Mother and Chicago's first department store? A lost Scottish castle that was blown to smithereens by the Territorial Army

By Melanie Bryan -

-

How much does this Georgian home turned artist's studio cost? Find out in the Country Life Quiz of the Day, February 23, 2026

By Country Life -

Feathers: Nature’s most exquisite miracle was fashioned for flight, fortitude and fantasy

By Charles Harris -

A Cambridgeshire cottage that was once home to a Cold War poet, five miles from 'the home of horse racing'

By Julie Harding -

'I loved defying the tyranny of fast fashion, one stitch at a time': Make do and mend is enjoying a creative revival

By Debora Robertson -

The only thing better than a stately home is a stately home in wooden miniature

By Will Hosie -

Chery Tiggo 9: Maybe the communists are onto something

By James Fisher

-

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

People & Places

-

-

The life of a BAFTA begins in an industrial estate in Braintree

-

The W1 set is up in arms about Liz Truss's roof terrace. But what is a members' club without one?

-

What have the Romans ever done for us? For one thing, taught us the art of seduction

-

‘I’m like: “Give me those tights, let me show you”: Ballet superstar Carlos Acosta’s consuming passions

-

Property

View all Property-

A Cambridgeshire cottage that was once home to a Cold War poet, five miles from 'the home of horse racing'

By Julie Harding -

-

The Shropshire boarding school that's lived multiple lives, transformed into a wonderful country house with the coolest cellar we've seen in years

By Julie Harding -

A 350-year-old estate in Barbados that’s hosted royals and Helen Mirren, furnished with 400 potted plants

By Rosie Paterson -

The seven best-kept secrets in the UK property market

By Annabel Dixon -

This Easter, give the gift of a small Welsh island

By Annabel Dixon -

A 16th century gatehouse for sale outside the castle where Henry VIII is thought to have pursued Anne Boleyn

By Annabel Dixon -

A Cluedo board rendered real at a country pile with 19 bedrooms, and a gym in the chapel

By Toby Keel

-

Architecture

View all Architecture-

What binds the Queen Mother and Chicago's first department store? A lost Scottish castle that was blown to smithereens by the Territorial Army

By Melanie Bryan -

-

The only thing better than a stately home is a stately home in wooden miniature

By Will Hosie -

'I have never ceased talking of the beauty of Ampthill': The tale of one of Britain's best-loved country houses

By Jeremy Musson -

Les Espaces d'Abraxas: 'Building a Versailles for the people in Noisy-le-Grand'

By Tim Abrahams -

'A fantastic creation, with the magic of a strange, dreamed, longed-for world': Inside Schloss Charlottenhof, the Prussian royal family's exquisite sanctuary

By Aoife Caitríona Lau -

The magnificent London mansion that Country Life mourned when it was demolished to make room for the Dorchester Hotel

By Melanie Bryan -

Repton: The 500-year-old school with a medieval priory whose story leads back to the kings of Mercia

By David Robinson -

The striking Arts & Crafts country home with interiors by William Morris that disappeared without a trace

By Melanie Bryan

-

Our expert voices

Interiors

View All Interiors-

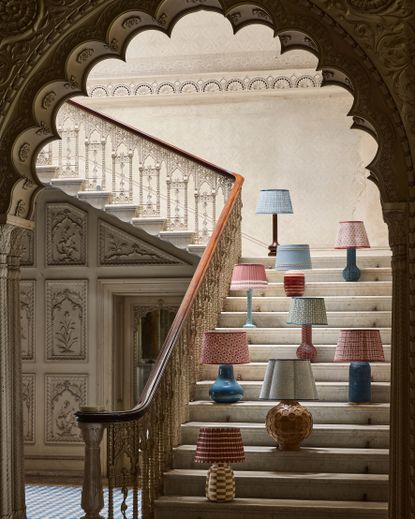

London Design Week: What to look out for at next month's unmissable interiors event

By Amelia Thorpe -

-

How do you add historic character back into a soulless room?

By Arabella Youens -

This clever interiors trick is the secret to creating multifunctional spaces — and it was integral to the design of many English country houses of the past

By Giles Kime -

'It was a complete wreck': Reclaiming a Hampshire coaching house from the earth

By Arabella Youens -

How do you add a dash of theatricality to a 1930s house? By taking inspiration from the legendary architect and set designer Oliver Messel

By Arabella Youens -

Are you a curator, a sympathiser or a conscientious objector? Take our Interiors Editor's quiz to discover your design DNA

By Giles Kime -

‘The pair drove to Belgium in their Mini and returned with the chair wrapped in duvets’: The mother-and-daughter duo that brought a converted Cotswolds barn back to life

By Arabella Youens -

'You should need little reminding that the 1980s are back': Country Life's interior-design predictions for 2026

By Giles Kime

-

Gardens

View All Gardens-

Intrepid, enterprising, dedicated: The new generation of nursery owners creating the flowers we'll be enjoying for decades to come

By John Hoyland -

-

Alan Titchmarsh: Patience is in short supply today, but learning when to crack on and when to leave well alone will do your garden wonders

By Alan Titchmarsh -

Penns in the Rocks: The East Sussex garden created by Vita Sackville-West, with a little help from the huge boulders that stood here when dinosaurs walked the earth

By George Plumptre -

'I was utterly bewitched': The heartwarming success story of one of Britain's greatest rose-growers

By Charles Quest-Ritson -

William Robinson, the visionary gardener 150 years ahead of his time

By Tiffany Daneff -

'It was like going on a blind date... over a few glasses of wine our friendship was sealed and by three in the morning we had a plan': The creation of a spectacular Moroccan garden

By Kirsty Fergusson

-

LIFE & STYLE

View All LIFE & STYLE-

-

'I loved defying the tyranny of fast fashion, one stitch at a time': Make do and mend is enjoying a creative revival

By Debora Robertson -

Chery Tiggo 9: Maybe the communists are onto something

By James Fisher -

The revolutionary dog that almost became Ireland’s national breed

By Victoria Marston -

William of Orange, Henry VIII and Shakespeare all fell under the spell of posey rings — once England's most popular item of jewellery

By Jonathan Self

-

THE COUNTRYSIDE

View All THE COUNTRYSIDE-

-

Feathers: Nature’s most exquisite miracle was fashioned for flight, fortitude and fantasy

By Charles Harris -

Britain's most widespread bird is also the most elusive — spotting it is one of ornithology’s great joys

By Mark Cocker -

Love is all around us, just ask the natural world

By James Fisher

-

ART & CULTURE

View all ART & CULTURE-

-

Pushing back against a culture of disposability: The enduring importance of craft

By Corinne Julius -

'He allowed lion and a tiger to prowl around the castle and, if an unfortunate servant was mauled, they were paid compensation': Exotic animals in art

By Michael Prodger -

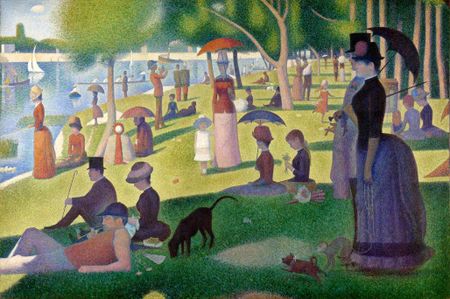

'He was really the most radical artist of the 19th century': Georges Seurat at the Courtauld Gallery

By Carla Passino -

This Civil War coat and armour has survived four centuries in almost perfect condition — apart from the hole made by the musket ball that killed the man who wore it

By John Goodall

-

Travel

View All Travel-

Hôtel du Couvent: This former convent on the French Riviera has rekindled the rules of luxury

By James Fisher -

-

This Hollywood star's home in the Canadian wilderness is now an exclusive-use lodge

By Rosie Paterson -

The real challenge facing Britain's grande dame seafront hotels

By Athena -

Couples are changing how they holiday — even on honeymoon

By Rosie Paterson -

The Cotton House review: If you're going to be the only hotel on Mustique, you better be great

By Rosie Paterson -

Is this London’s sexiest hotel room?

By Lotte Brundle

-

Food & Drink

View All Food & Drink-

‘French pastries all look amazing… but I wish more British bakers would look at what we used to have’: Richard Hart on the joys of jammy dodgers and iced buns

By Oliver Berry -

-

Where's the rum gone? How the temperance movement took on the Royal Navy

By Henry Jeffreys -

Tom Parker Bowles: 'There is no dish more lusty and full blooded than boeuf à la Bourguignonne'

By Tom Parker Bowles -

The 'chef's table' is off the ick list

By Emma Hughes -

Sophia Money-Coutts: A snob's guide to supermarkets and what to do when there's no Waitrose

By Sophia Money-Coutts -

Patrick Galbraith: 'The idea that a bar in Norfolk selling vinho verde would make it through even one winter was about as likely as the Madonna herself reappearing by the old water pump'

By Patrick Galbraith -

Agromenes: The Food Waste Inspector is right to call out M&S, Waitrose and Lidl for throwing away food that is perfectly good to eat

By Agromenes

-