When a breed no longer has a job, be it turning a meat spit, hunting or herding, it often goes the way of the dodo. Patrick Galbraith recalls 10 extinct British dogs.

The Kennel Club’s librarian Ciara Farrell has ‘two fat old cats’ and admits that, when she started her job, she ‘knew nothing about dogs’. Fifteen years later, however, she’s in her element, trawling through Jacobean manuscripts and Victorian diaries to aid my quest to discover Britain’s lost dogs.

‘I notice some of the breeds you’re interested in might be better described as types,’ she comments sagely, as I leaf through De Canibus: Dog and Hound in Antiquity. ‘If I’m talking about dogs before the 1850s, I try never to use the word “breed”. I use the words “breed type” and, even further back than that, I just say “type”.’

The notion of breeds was conceived in Victorian England, Miss Farrell explains, when the nation fell in love with dog shows, which necessitated a breed standard to judge one dog against another. Interestingly, the Temperance Movement keenly promoted dog shows as a sober and self-improving way to spend a Saturday. Miss Farrell confirms that those who attend Crufts today are still a well-behaved and generally sober sort.

Before the mid 19th century, dogs were grouped according to various practical uses. As those uses diminished, breeds suffered – the endangered Glen of Imaal terrier (adorably pictured above) cannot legally fulfil its badger-hunting purpose and the wolfhound has been out of a job for years.

Will there be new breeds, I ask, as we wander round the gallery, past cabinets of china pugs, a huge Landseer and contemporary bronzes. ‘You’re not going to see many breeds of dog coming into being because, nowadays, we have so few canine-specific tasks,’ Miss Farrell reflects. ‘Instead, dogs are repurposed. The trainability and temperament of the retriever, for example, which made it so good for shooting, mean they are used as assistance dogs.’

How about notoriously unhelpful terriers? Well, there’s always Instagram, she explains. If a breed is in dire straits, The Kennel Club fires up social media and launches a very modern campaign to try to save it.

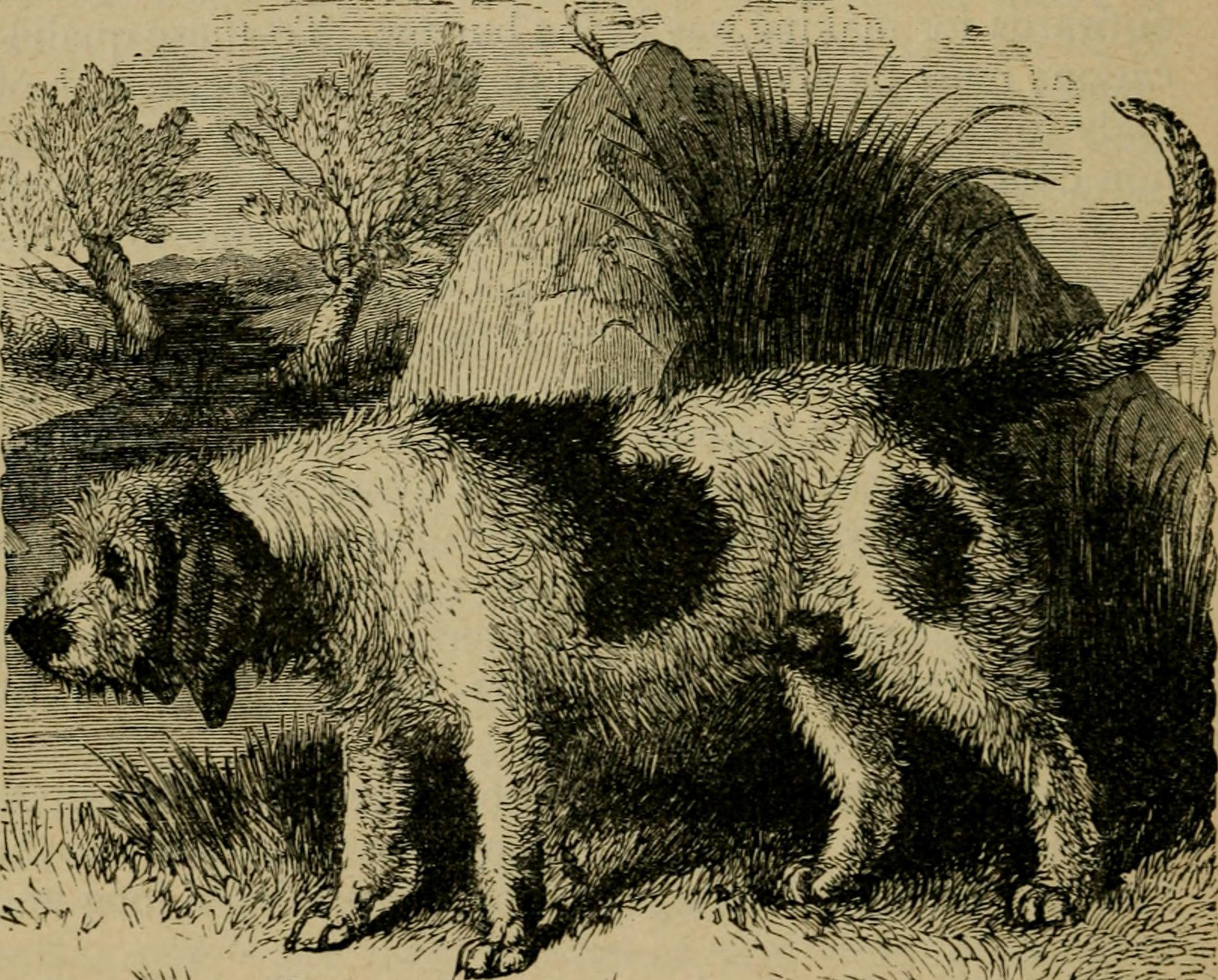

Turnspit dog

Turnspit dog at work. These short-legged dogs were bred especially to work in wheels turning cooking spits. By 1800 the breed had almost disappeared. Wood engraving, c1880.

In a Regency hunting lodge, within the grounds of Abergavenny Castle, is a stuffed dog called Whiskey. He is the last of his kind: a turnspit dog. These squat, long-backed animals ran on wheels in kitchens to turn meat as it cooked. Throughout the winter months, they were also taken to church as foot warmers. It is said that, during a church service in Bath, the Bishop of Gloucester proclaimed, ‘It was then that Ezekiel saw the wheel’, and several turnspit dogs ran for the door.

Feeling sorry for the little animals, Queen Victoria kept retired ones as pets. As the 19th century progressed, keeping a dog to turn your meat rather than using a machine came to be seen as a sign of poverty. By 1850, the dogs had become scarce and, by 1900, they had completely disappeared.

Blue Paul terrier

The plucky Blue Paul terrier was a favourite breed among Scottish tinkers, who deemed the dogs to be rather handy at fighting. It’s often said that John Paul Jones, the founder of the American navy, brought them back from some far-flung reach of the New World when visiting his native Kirkcudbrightshire. A less romantic, and perhaps more realistic, theory is that the breed’s origins lay in crossing bulldogs with the handsome Irish Blue terrier.

At some point in the latter half of the 19th century, the breed became extinct, but through historic inter-breeding, the curious coloration lives on in the blue pit bull.

Paisley terrier

In 1894, eminent dog writer Rawdon Briggs Lee described the Paisley terrier as ‘most suitable for a lady’. The high-maintenance little creature had a silky coat ‘like a silvery, soft jacket’ and was essentially a show dog, but could reportedly kill rats when necessary.

It’s believed that the Paisley was bred by terrier fanciers in Glasgow, who used short and long Skye terriers. In the 1900s, as the popularity of dog shows declined, the breed disappeared. However, it’s often cited as the progenitor of the scrunchie-wearing Yorkshire terrier.

Talbot hound

Readers who are well versed in heraldry will know that, on crests such as the Earl of Waldegraves, the talbot hound denotes a mannerly hunting dog. It’s unclear when the lumbering white breed first became established in England, but a dog named ‘talbot’ is referenced in Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales and the type appears to have been commonplace on the 17th-century hunting field.

Famed for their noses, the dogs worked slowly and, as shorter, faster hunts became fashionable, the talbot fell out of favour. By 1800, it had been usurped completely by the beagle and the foxhound.

English water spaniel

Those who know their Shakespeare will recall that, in The Two Gentlemen of Verona, the servant Launce announces his sweetheart ‘hath more qualities than a water-spaniel’. These lovely qualities, according to Sportsman’s Cabinet in 1802, included ‘long and naturally curled hair’ and being able to dive as well as a duck.

An Irish water spaniel.

During the first half of the 18th century, the English water spaniel was common in East Anglia, where the dogs were used by wildfowlers. Over time, they were surpassed in popularity by the labrador and were absorbed into other spaniel breeds. According to records, the last one was seen in 1912.

Welsh hillman

Believed to be descended from the Welsh wolfhound, which was used more than 1,000 years ago, the hillman was a fast and fearless herding dog. Old pictures show an animal that looked rather like a sleek German shepherd.

Offa’s Dyke near Montgomery, Powys, Wales, UK.

The last Welsh hillman was reportedly bought from a farm in Powys in 1974. Not recognising the rarity of the breed, the new owner had the dog spayed, bringing an inglorious end to a noble chapter in British canine history.

Bull and terrier

In 1823, a dog named Billy secured his place as the world’s most famous bull and terrier by killing 100 rats in 5½ minutes. As the name suggests, the breed was the result of crossing a variety of old terrier types with the English bulldog. In 1859, Stonehenge – the pen name of John Henry Walsh, editor of The Field from 1857 – described the breed as a ‘strong, useful little dog with great endurance’.

Purists argue that the bull and terrier wasn’t a breed in the true sense of the word and, therefore, it didn’t so much become extinct as evolve into the likes of the Staffordshire bull terrier, which was recognised as an official breed in 1935.

Celtic hound

In Irish mythology, the Celtic hound is emblematic of great courage and loyalty. Little is known about the ancient breed, but it is thought to be the progenitor of the Irish wolfhound and of the hare-hunting Galgo Español. As well as coursing game, it was used in war to drag warriors from their saddles.

Interestingly, there is evidence that the hounds’ qualities were appreciated abroad – letters about them were displayed as curiosities in Ancient Rome.

North Country beagle

The North Country beagle, recorded William Nicholson in 1809, ‘was kept by a dashing class of sportsmen’ because it could ‘run down a brace [of hares] before dinner’. However, in the decades that preceded Nicholson writing those words, the sporting field had shifted up a gear. Fox-hunting was in vogue and the foxhound, with its exceptional nose and even greater pace, was in ascendancy.

Just your normal, every day beagle.

By 1833, the young Stonehenge wrote that he didn’t think there were any hounds still hunting in England that were true North Country beagles.

Smithfield

Although they were never officially recognised by The Kennel Club, Smithfields were a common sight in Victorian London, where they were used to herd livestock on the way to market. Very little is known about the origins of the breed, but it is said to have had the appearance of an old English sheep dog, with the pluckiness and drive of a terrier.

It isn’t clear when the breed became extinct in England, but, in the early 19th century, a number of Smithfields were taken to Australia, where they were crossed with other droving dogs to create a similar breed that is still used in Tasmania today.

The top ten British dog breeds that need saving and quickly

French bulldog wins top spot over labrador as some of the most quintessentially British breeds are pronounced 'vulnerable' by the

One of our most ancient country houses, tragically gutted by fire, is in need of saving and fast

One of the oldest, largest and most beautiful country houses in England has come up for sale – and while

Glen of Imaal terriers: Wilful, adorable and sadly extremely vulnerable

They’re one of our most vulnerable native breeds – but what Glen of Imaal terriers lack in numbers, they make

Tibetan terriers: Friend to the famous, lovably lively and perhaps the Kennel Club’s best-kept secret

They have a starry following, but characterful Tibetan terriers are still a well-kept secret. Emma Hughes meets the best dog

Fox-red labradors: Why red is the new black

From russet red to ever-so-slightly blushed, the fox-red is growing in popularity across the country sporting world. However, the gundog

The rhino who reads Country Life

Yes - really. Monty the rhino enjoyed his Country Life fame so much that he had to have a look

Cavalier King Charles spaniels: Handsome, good-natured and the aristocrats of the dog world

With a silken coat, affectionate nature and boundless enthusiasm for life, the Cavalier King Charles spaniel lives up to its

Curious Questions: What dog should Boris Johnson get as the new pet for No. 10 Downing Street?