In the middle of winter, we cut down fir trees, bring them inside and decorate them – then let them shed small, spiky needles throughout our homes. Why would we do such a thing? Toby Keel investigates.

As anyone who’s brought a Christmas tree into their house this year can attest, it’s not exactly the most practical proposition. Getting it onto the car, off the car, through various doorways, into the living room and into the bucket is bad enough, but then trying to weigh the bucket down (this year with old roof tiles, since the bricks we normally use have disappeared) while keeping the tree straight sees things descend into farce.

What’s more, the tree is dying before it even brings the room to life. We hoovered five times the first afternoon alone, while we’ve already starting finding needles on the carpets upstairs. Future humans, thousands of years hence, will probably look at our little custom rather as we look back at those who worship carved tree stumps.

Yet we wouldn’t be without it. Christmas at our house begins when the tree is up – the watershed moment after which you’ll no longer get frowned at for pinching something from the Quality Street box.

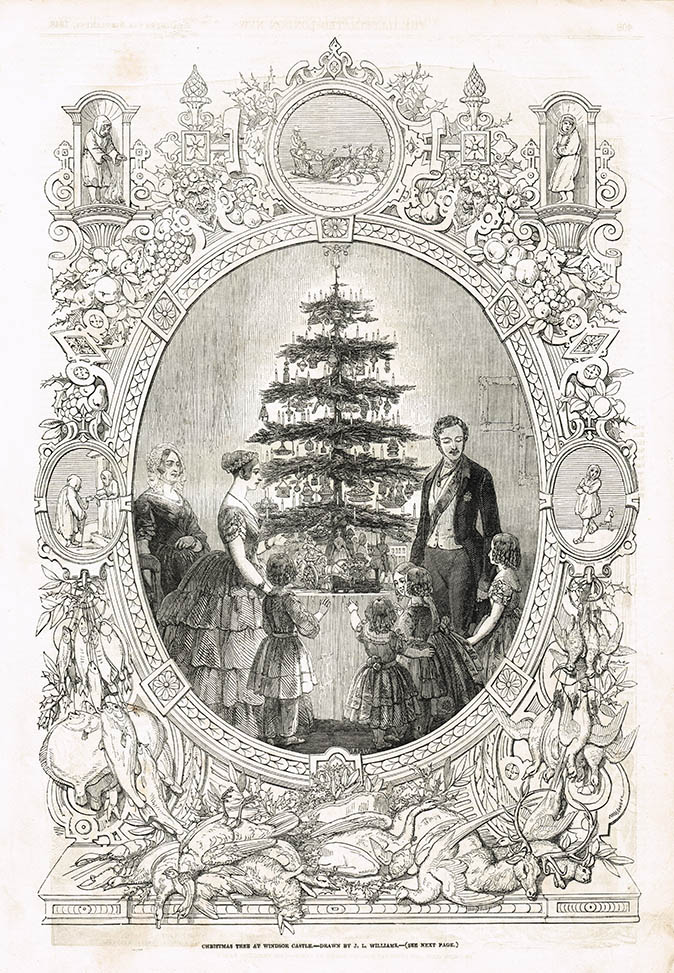

Why do we do it, though? The popularity of Christmas trees is most often traced back to the Victorians, and specifically Queen Victoria’s appearance with her family on a widely-reproduced Christmas picture drawn in 1848 of ‘Christmas at Windsor Castle’. Prince Albert reputedly brought the tradition with him from Germany.

Victoria, Albert and the Royal Family gathering around the Christmas Tree at Windsor Castle in 1848 (Pic: Alamy)

As ever with our Curious Questions, the most-repeated story is only a part of the story. For starters, Albert didn’t invent anything – he merely did with his family in England what he’d grown up doing with his family in Germany. So where did the Germans get the idea?

A little Googling will tell you that the answer is ‘from Martin Luther’. During a nighttime walk through a forest, the church reformer was apparently so moved by the sight of the starry heavens glimpsed through the branches above that he chopped one of the trees down and brought it inside, to remind him and his children of the heavens from which their saviour came.

Yet as romantic as that story is, Martin Luther too was probably beaten to it. The Latvian city of Riga claims to have had the first decorated Christmas tree in 1510, some 15 years before Luther got married. Not much is known about the Riga tree, though it stood in the marketplace and was burnt afterwards.

Riga’s claim on the invention of the Christmas tree has a serious rival, however, from the pagans of northern Europe. Historians believe that tree worship was important to pagans, and that evergreens were used at the festival of the midwinter solstice to remind those present of the coming spring. As ever with pagan history it’s impossible to speak with any precision or certainty, least of all when it comes to dates, but there is evidence to suggest that this tradition began long before the birth of Christ.

And with that, the true story probably emerges. For all its faults (most of which were enumerated by the aforementioned Luther) the medieval church was outstandingly good at folding its own teachings into people’s everyday lives. Take marriage, for example: it was an entirely secular arrangement in the first millennium and beyond, but from the 12th century onwards the church embraced it as a sacrament. Even the date of Christmas itself, only decided by the church almost 400 years after Christ’s birth, was almost certainly selected to coincide with the popular Roman and pagan celebrations of Saturnalia.

Thus it seems likely that a pagan tradition of midwinter home decoration found itself mixed up with Christianity – perhaps with elements of the ‘Jeu d’Adam’ paradise plays thrown in too. They were popular from the 12th century onwards, and linked the Tree of Knowledge in the Garden of Eden to the promise of the Saviour’s coming.

It’s funny how the history of such things mirrors the twists and turns of evolution. There’s something to think about when you’re still finding fir tree needles in the rug next April.