-

Pushing back against a culture of disposability: The enduring importance of craft

By Corinne Julius -

-

Hôtel du Couvent: This former convent on the French Riviera has rekindled the rules of luxury

By James Fisher -

Intrepid, enterprising, dedicated: The new generation of nursery owners creating the flowers we'll be enjoying for decades to come

By John Hoyland -

The real rock stars: Meet the makers of the Olympic curling stones

By Harry Pearson -

A 350-year-old estate in Barbados that’s hosted royals and Helen Mirren, furnished with 400 potted plants

By Rosie Paterson -

It's fashion, darling — and the Country Life Quiz of the Day, February 20, 2026

By Country Life -

Amanda Seyfried's new film answers the question: Where did the viral Instagram Shaker kitchen come from — and how is it linked to Quakerism?

By Alexandra Goss

-

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

People & Places

-

-

The life of a BAFTA begins in an industrial estate in Braintree

-

The W1 set is up in arms about Liz Truss's roof terrace. But what is a members' club without one?

-

What have the Romans ever done for us? For one thing, taught us the art of seduction

-

‘I’m like: “Give me those tights, let me show you”: Ballet superstar Carlos Acosta’s consuming passions

-

Property

View all Property-

A 350-year-old estate in Barbados that’s hosted royals and Helen Mirren, furnished with 400 potted plants

By Rosie Paterson -

-

The seven best-kept secrets in the UK property market

By Annabel Dixon -

This Easter, give the gift of a small Welsh island

By Annabel Dixon -

A 16th century gatehouse for sale outside the castle where Henry VIII is thought to have pursued Anne Boleyn

By Annabel Dixon -

A Cluedo board rendered real at a country pile with 19 bedrooms, and a gym in the chapel

By Toby Keel -

'The most beautiful house for sale in London' is a six-bedroom home with a walled garden that backs on to Greenwich Park

By Will Hosie -

12 wonderful homes, from a Cotswolds mill to a country house within the M25, as seen in Country Life

By Toby Keel

-

Architecture

View all Architecture-

Les Espaces d'Abraxas: 'Building a Versailles for the people in Noisy-le-Grand'

By Tim Abrahams -

-

'A fantastic creation, with the magic of a strange, dreamed, longed-for world': Inside Schloss Charlottenhof, the Prussian royal family's exquisite sanctuary

By Aoife Caitríona Lau -

The magnificent London mansion that Country Life mourned when it was demolished to make room for the Dorchester Hotel

By Melanie Bryan -

Repton: The 500-year-old school with a medieval priory whose story leads back to the kings of Mercia

By David Robinson -

The striking Arts & Crafts country home with interiors by William Morris that disappeared without a trace

By Melanie Bryan -

'The Shakespeare of architects... he has yet had no equal in this country': Sir John Vanbrugh and the legacy of Blenheim Palace

By Charles Saumarez Smith -

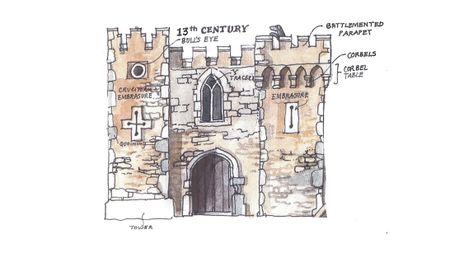

Can you tell the difference between a trefoil and an embrasure? A pictorial guide to medieval architecture

By Toby Keel -

Lord Byron, Charles Dickens and Sir Walter Scott once dined at this Jacobean mansion in London. Destroyed by The Blitz it lives on now only in the Country Life Archive

By Melanie Bryan

-

Our expert voices

Interiors

View All Interiors-

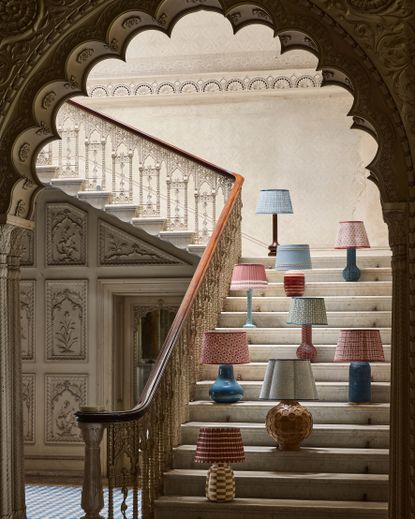

London Design Week: What to look out for at next month's unmissable interiors event

By Amelia Thorpe -

-

How do you add historic character back into a soulless room?

By Arabella Youens -

This clever interiors trick is the secret to creating multifunctional spaces — and it was integral to the design of many English country houses of the past

By Giles Kime -

'It was a complete wreck': Reclaiming a Hampshire coaching house from the earth

By Arabella Youens -

How do you add a dash of theatricality to a 1930s house? By taking inspiration from the legendary architect and set designer Oliver Messel

By Arabella Youens -

Are you a curator, a sympathiser or a conscientious objector? Take our Interiors Editor's quiz to discover your design DNA

By Giles Kime -

‘The pair drove to Belgium in their Mini and returned with the chair wrapped in duvets’: The mother-and-daughter duo that brought a converted Cotswolds barn back to life

By Arabella Youens -

'You should need little reminding that the 1980s are back': Country Life's interior-design predictions for 2026

By Giles Kime

-

Gardens

View All Gardens-

Intrepid, enterprising, dedicated: The new generation of nursery owners creating the flowers we'll be enjoying for decades to come

By John Hoyland -

-

Alan Titchmarsh: Patience is in short supply today, but learning when to crack on and when to leave well alone will do your garden wonders

By Alan Titchmarsh -

Penns in the Rocks: The East Sussex garden created by Vita Sackville-West, with a little help from the huge boulders that stood here when dinosaurs walked the earth

By George Plumptre -

'I was utterly bewitched': The heartwarming success story of one of Britain's greatest rose-growers

By Charles Quest-Ritson -

William Robinson, the visionary gardener 150 years ahead of his time

By Tiffany Daneff -

'It was like going on a blind date... over a few glasses of wine our friendship was sealed and by three in the morning we had a plan': The creation of a spectacular Moroccan garden

By Kirsty Fergusson

-

LIFE & STYLE

View All LIFE & STYLE-

-

William of Orange, Henry VIII and Shakespeare all fell under the spell of posey rings — once England's most popular item of jewellery

By Jonathan Self -

I'm thinking about the ice and wasting an afternoon on Autotrader

By James Fisher -

Forget the sex, the real talking point of 'Wuthering Heights' is Margot Robbie's vintage brooches

By Amie Elizabeth White -

Fashion fit for the Winter Olympics (sort of) from the Country Life Archive

By Melanie Bryan

-

THE COUNTRYSIDE

View All THE COUNTRYSIDE-

-

Britain's most widespread bird is also the most elusive — spotting it is one of ornithology’s great joys

By Mark Cocker -

Love is all around us, just ask the natural world

By James Fisher -

The short-eared owl is a breed apart

By Mark Cocker

-

ART & CULTURE

View all ART & CULTURE-

-

Pushing back against a culture of disposability: The enduring importance of craft

By Corinne Julius -

'He allowed lion and a tiger to prowl around the castle and, if an unfortunate servant was mauled, they were paid compensation': Exotic animals in art

By Michael Prodger -

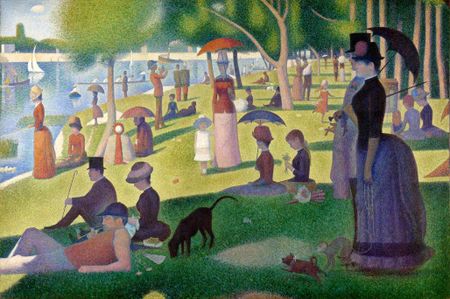

'He was really the most radical artist of the 19th century': Georges Seurat at the Courtauld Gallery

By Carla Passino -

This Civil War coat and armour has survived four centuries in almost perfect condition — apart from the hole made by the musket ball that killed the man who wore it

By John Goodall

-

Travel

View All Travel-

Hôtel du Couvent: This former convent on the French Riviera has rekindled the rules of luxury

By James Fisher -

-

This Hollywood star's home in the Canadian wilderness is now an exclusive-use lodge

By Rosie Paterson -

The real challenge facing Britain's grande dame seafront hotels

By Athena -

Couples are changing how they holiday — even on honeymoon

By Rosie Paterson -

The Cotton House review: If you're going to be the only hotel on Mustique, you better be great

By Rosie Paterson -

Is this London’s sexiest hotel room?

By Lotte Brundle

-

Food & Drink

View All Food & Drink-

‘French pastries all look amazing… but I wish more British bakers would look at what we used to have’: Richard Hart on the joys of jammy dodgers and iced buns

By Oliver Berry -

-

Where's the rum gone? How the temperance movement took on the Royal Navy

By Henry Jeffreys -

Tom Parker Bowles: 'There is no dish more lusty and full blooded than boeuf à la Bourguignonne'

By Tom Parker Bowles -

The 'chef's table' is off the ick list

By Emma Hughes -

Sophia Money-Coutts: A snob's guide to supermarkets and what to do when there's no Waitrose

By Sophia Money-Coutts -

Patrick Galbraith: 'The idea that a bar in Norfolk selling vinho verde would make it through even one winter was about as likely as the Madonna herself reappearing by the old water pump'

By Patrick Galbraith -

Agromenes: The Food Waste Inspector is right to call out M&S, Waitrose and Lidl for throwing away food that is perfectly good to eat

By Agromenes

-