Thomas Cole left Britain behind as a teenager and became one of America's great painters. Lilias Wigan takes a look at one of his most powerful and moving works – one with a message which rings truer than ever today.

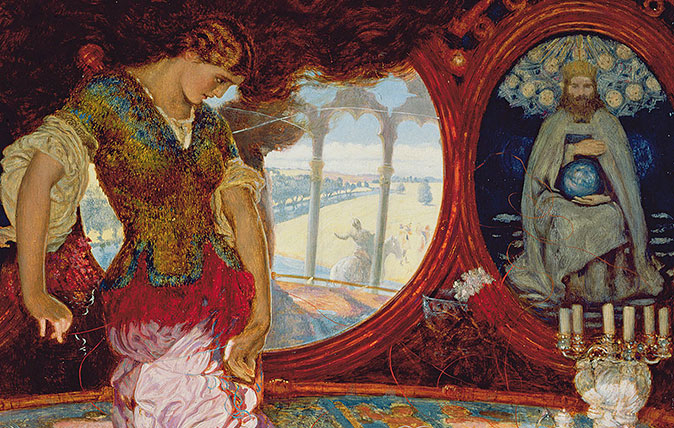

Thomas Cole, The Course of Empire: The Pastoral or Arcadian State, about 1834. Oil on canvas, 99.7 × 160.6 cm. National Gallery, courtesy of the New-York Historical Society © Collection of The New-York Historical Society, New York / Digital image created by Oppenheimer Editions

Born the son of an unsuccessful textile manufacturer in Bolton, Lancashire, at the height of the industrial revolution, Thomas Cole (1801-1848) was to move to the United States and become the leading American landscape painter of the nineteenth century. Today, he is the subject of a new exhibition in the land of his birth: Thomas Cole: Eden to Empire is on view at the National Gallery until 7th October 2018.

As a young man of 17, Cole and his family emigrated and he worked as a wood engraver in Pennsylvania. By the age of 24 he had settled in New York, from where he made a crucial trip to the Hudson River and Catskill Mountains, both of which became subjects in his work. After achieving success and gaining a number of supportive patrons, he embarked on a three year Grand Tour of Europe in 1829. On this expedition, he was exposed to the Age of Romanticism, as well as the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution — a period of change that prompted further visual creativity.

Cole’s most ambitious work was an allegorical five-part series titled The Course of Empire. In the drama of the series, which presents the rise and fall of a mythical civilization, the wilderness of an American landscape is gradually destroyed by the endless gluttony, decadence and interference of its human inhabitants. Cole’s significance lies not only as the father of American landscape painting, but in his moralistic narrative and expression of concern for the natural environment, setting him apart from his contemporaries.

The Pastoral or Arcadian State of c. 1834 is the second work in the cycle. It depicts an idyllic, pastoral landscape in the period before deterioration unfolds.

Cole was raised as a Calvinist and had a strong belief in the doctrine of predestination. He saw nature as God’s gift to the human race and thought that its destruction would be caused by man’s desire for consumption in the new industrial age. As a teenager, he had witnessed Luddite fires in the Lancashire mills and he was especially conscious of the threat of mechanical revolution.

In the scene here, however, the residents appear to be living in harmony with their environment. The land has been cultivated; pastures have been made and trees pruned. An even, golden light illuminates the rich green vegetation. As America modernizes and its economy booms, Cole presents us with a pastoral Arcadia.

Snippets of scenes dotted about the canvas balance nature and human life. On the right, youths dance to piped music and a river boat prods at maritime trade. In the foreground, a young boy draws a stick figure onto the rock with Cole’s initials beneath it — an implication that the artist has much to learn or perhaps to suggest the birth of painting? The great temple-like structure encircling a fire recalls Stonehenge, a nod to the rituals of Pagan religion (as well as to England).

The painting also poses questions about cultivation and initiates feelings of foreboding. A soldier in arms suggests that war that is an inevitable consequence of the human condition, a threat echoed by the two butting rams seen in the distance.

Cole’s introduction to the painting reads: “The Simple or Arcadian State represents the scene after ages have passed. The gradual advancement of society has wrought a change on its aspect. The ‘untracked and rude’ has been trained and softened. Shepherds are tending to their flocks, the ploughman with his oxen, is upturning the soil, and commerce begins to stretch her wings.” Even in this description of an imagined world of perfection, there’s a tinge of unease to the language; Cole favours the American wilderness.

One immutable element throughout the cycle is the cliff, with a boulder perched precariously at its summit, a subtle reminder that the earth’s foundations are not immune to the consequences of man. In questioning the effects of civilization and reflecting on the balance between progress and nature, Cole’s work has an uncanny resonance today.

Thomas Cole: Eden to Empire is on view at the National Gallery until 7th October 2018 – see more details and buy tickets at the National Gallery website. Coinciding with this exhibition is a free display of renowned LA-based artist Ed Ruscha’s own Course of Empire, showing his modern take on Cole’s series.

In Focus: The Degas painting full of life, movement and ‘orgies of colour’

Lilias Wigan takes a closer look at one of the key work's at the Degas exhibition at the National Gallery

In Focus: Michael Armitage’s image of African violence that points the finger back at the western world

Michael Armitage's The Flaying of Marsyas is the centrepiece of his exhibition in South London. Lilias Wigan examines it in

In Focus: The Van Dyck portrait that shows Charles I as monarch, connoisseur and proud father

Lilias Wigan takes a detailed look at Van Dyck's Greate Peece, one of the highlights of the Royal Academy's stunning

In Focus: How Holman Hunt’s Lady of Shallot was inspired by Van Eyck’s greatest masterpiece

Holman Hunt was one of several pre-Raphaelites inspired by Jan Van Eyck's iconic The Arnolfini Portrait. Lilias Wigan takes an

In Focus: The Norman Ackroyd landscape etchings that have sparked comparisons with Turner

This week marks the last chance to see Norman Ackroyd's sublime exhibition in Richmond. Lilias Wigan urges you to take

In Focus: The breathtaking sculpture at the V&A with unexplained, frenzied figures writhing in pleasure and pain

Rachel Kneebone's towering sculpture at the centre of some of the V&A's oldest treasures demands your attention in a way