-

Reimagined by Sir Edwin Lutyens for Victoria Sackville-West, a Brighton home for sale in the Regency square that inspired 'Alice in Wonderland'

By Annabel Dixon

-

-

From Boudica to Bohemian Rhapsody: how well do you know your queens? Find out in the Country Life Quiz of the Day, January 15, 2026

By Country Life

-

Three plants to grow in 2026 that are as delicious as they are pretty, from Siberian chives to 'Turkish warty cabbage'

By Mark Diacono

-

The Glovebox: Fashion that's fast and five of our favourite Concours for 2026

By James Fisher

-

‘The pair drove to Belgium in their Mini and returned with the chair wrapped in duvets’: The mother-and-daughter duo that brought a converted Cotswolds barn back to life

By Arabella Youens

-

Best country houses for sale this week

By Country Life

-

Make sure you don't skip these South of England art and history highlights

By Charlotte Mullins

-

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

People & Places

-

-

Six things that Britain should be proud of, from world-class restaurants and Championship-winning cars to the countryside

-

Gavin Plumley: Shakespeare’s country isn’t Stratford-upon-Avon, it’s the quiet and beautiful Herefordshire countryside where Hamnet was filmed

-

How an eco-friendly interior designer transformed a former milking parlour into a multi-purpose space in the middle of the Pandemic

-

The 400-year-old floors perfectly preserved in the house that inspired Charles Dickens to create Miss Havisham's mansion

-

Property

View all Property-

Reimagined by Sir Edwin Lutyens for Victoria Sackville-West, a Brighton home for sale in the Regency square that inspired 'Alice in Wonderland'

By Annabel Dixon

-

-

Best country houses for sale this week

By Country Life

-

A six-bedroom Highland lodge on the shores of Loch Ness for the price of a modest London flat

By Julie Harding

-

The world's grandest student house is for sale, with cinema, steam room, roof garden, and a starring role as Oscar Wilde's Bohemian hotspot

By Lotte Brundle

-

Six great country houses, from £1.2 million to £13.5 million, as seen in Country Life

By Toby Keel

-

A 1960s pop star's 'iconic' mansion right by the water's edge in one of prettiest spots on the Thames

By Toby Keel

-

This treasure-filled palace for sale was built by one of the greatest architects of the 18th century, and became the birthplace of Italy as we know it

By Toby Keel

-

Our expert voices

Interiors

View All Interiors-

‘The pair drove to Belgium in their Mini and returned with the chair wrapped in duvets’: The mother-and-daughter duo that brought a converted Cotswolds barn back to life

By Arabella Youens

-

-

'You should need little reminding that the 1980s are back': Country Life's interior-design predictions for 2026

By Giles Kime

-

How an eco-friendly interior designer transformed a former milking parlour into a multi-purpose space in the middle of the Pandemic

By Grace McCloud

-

How Britain’s biggest and best country houses are decking the halls (and façades) for Christmas

By Bella Fulford

-

Giles Kime: Cushions, rugs, upholstered stools and sofa blankets are the ingredients of a pleasing new trend

By Giles Kime

-

John Goodall: Restoration is 'an act of recycling', but we need a system that encourages it

By John Goodall

-

Making space in a Georgian terraced Chelsea cottage

By Arabella Youens

-

Moths and memories of the Russian Revolution: Why it's worth saving that tired old rug

By Catriona Gray

-

LIFE & STYLE

View All LIFE & STYLE-

-

The Glovebox: Fashion that's fast and five of our favourite Concours for 2026

By James Fisher

-

Make sure you don't skip these South of England art and history highlights

By Charlotte Mullins

-

The seven artistic wonders of the Midlands to put on your bucket list

By Charlotte Mullins

-

From the front line to the front row: A potted history of the Wellington boot and some of our favourites to buy right now

By Amie Elizabeth White

-

COUNTRYSIDE

View All THE COUNTRYSIDE-

-

Hamnet won the top film award at the 2026 Golden Globes — but where in the British countryside was it filmed?

By Gavin Plumley

-

Endangered bumblebees, sifting spoonbills and trespassing tortoises: Britain's railway network is a wildlife haven

By Vicky Liddell

-

Two turtle doves: Why the endearing bird is an animal for all seasons, not just Christmas

By Mark Cocker

-

Gardens

View All Gardens-

Three plants to grow in 2026 that are as delicious as they are pretty, from Siberian chives to 'Turkish warty cabbage'

By Mark Diacono

-

-

Seeing the centuries old specimens of Carl Linnaeus in a new light

By Christopher Stocks

-

Alan Titchmarsh: Everything you think you know about ivy is probably wrong

By Alan Titchmarsh

-

The railway station gardens that bring a touch of bucolic bliss to an ordinary train ride

By Andrew Martin

-

The Convent Garden of Il Redentore: A Venice masterpiece that's finally opened its gates after 450 years of total privacy

By Tim Richardson

-

Country Life's top 10 garden stories of 2025, from Alan Titchmarsh's hardy annuals to David Beckham's Cotswolds paradise

By Toby Keel

-

ART & CULTURE

View all ART & CULTURE-

-

The 'micro mosaic' at Holkham Hall that uses a fascinating, unusual technique pioneered by the Vatican

By John Goodall

-

Tate-à-tête: The National Gallery’s promise to grow its modern-art collection risks reopening old wounds

By Will Hosie

-

Forget Bond, the understated George Smiley is fiction's greatest spy

By Emma Hughes

-

‘I wasn’t really sure that I wanted to be a ballet dancer’: The English National Ballet's prima ballerina on playing Clara in The Nutcracker and her consuming passions

By Lotte Brundle

-

Travel

View All Travel-

Above the clouds to beat the crowds: Where to stay in Wales if you want to conquer the 'other' Snowdon

By Tiffany Daneff

-

-

Inside the 19th century château in St Tropez where hotel guests are ferried to the beach in Rolls-Royces and season four of The White Lotus is about to start filming

By Rosie Paterson

-

Revelstoke is the heli-skiing capital of the world, where legendary powder, lethal lines and famous names collide

By Adam Hay-Nicholls

-

This new hotel medi-spa in Morocco has got tongues wagging for all the right reasons — and it’s nearly as big as The White House

By Jennifer George

-

Country Life's top 10 travel articles of 2025, including the Scottish survival experience beloved by David Beckham and what a A-list ski resort does when it stops getting snow

By Rosie Paterson

-

The railway revolution: 'The most profound change to British society since the arrival of the Normans, perhaps even the Romans'

By Jonathan Self

-

Food & Drink

View All Food & Drink-

The enduring allure of menus from ancient civilisations to modern day, via the revolutionary France

By John F. Mueller

-

-

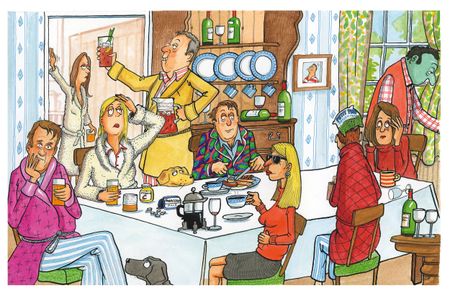

The 12 types of hangover, from 'Backwards Binoculars' to 'Titanic', and how to cure them all

By Olly Smith

-

'We begin making in May and start packing and despatching in November — it’s carnage': How the Cotswolds' favourite cake-makers get ready for Christmas

By Jane Wheatley

-

Tim Wilson of The Ginger Pig on the perfect Christmas ham

By Jane Wheatley

-

East London's salmon smokehouse is full of secrets

By Tom Howells

-

Four festive recipes from the Country Life Archive that have (thankfully) fallen out of favour

By Melanie Bryan

-

Country Life's luxury editor's Christmas gift ideas for foodies, from traditional hampers to nifty kitchen gadgets

By Amie Elizabeth White

-