Matthew Dennison pays tribute to artists who painted our collective childhoods.

The work of the best children’s illustrators provides a layer of description impossible in words. Each of us remembers favourite images from our own childhood reading.

In a handful of cases, however, it goes beyond our personal experience. Some illustrators’ visions have transcended simple enhancement of the text, and have stamped themselves upon the national consciousness. We celebrate some of the best of them below.

Ernest Shepard

His illustrations to Milne’s text have come to evoke for several generations a sun-drenched vision of idyllic British childhood – the same quality characterises his illustrations to Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, undertaken in 1931.

– – – – –

Sir John Tenniel

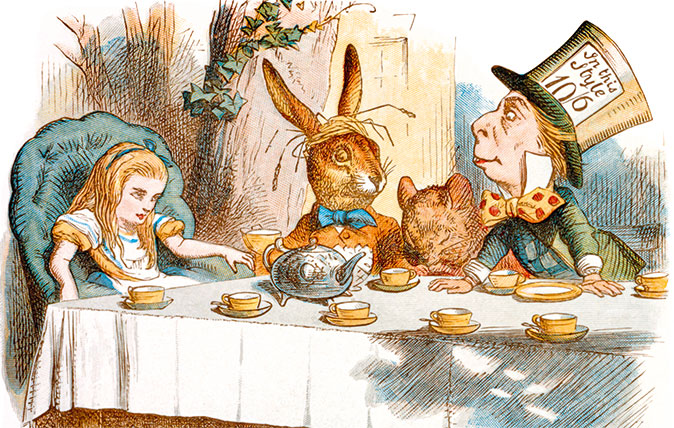

Like Shepard, Tenniel was a Punch illustrator who pondered Lewis Carroll’s invitation to illustrate Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland for three months before agreeing, on April 5, 1864, to a fee of £138 for 42 illustrations, which he produced over the course of the following year. So highly did Carroll value both Tenniel’s judgement and his work – on which he advised in some detail – that, in July 1865, he accepted Tenniel’s objections to the quality of the Clarendon Press’s first printing of his novel, rejected all 2,000 copies and switched to a new printer, Richard Clay.

Happily, Clay achieved the necessary clarity of detail in reproducing Tenniel’s illustrations as wood-block engravings and posterity is the richer for the swap. After 150 years, his White Rabbit, Mad Hatter and Red Queen remain instantly recognisable. His vision of Alice encapsulates mid-Victorian stereotypes of girlish prettiness and ‘Alice’ hairbands remain a feature of girls’ hairdressing.

– – – – –

Beatrix Potter

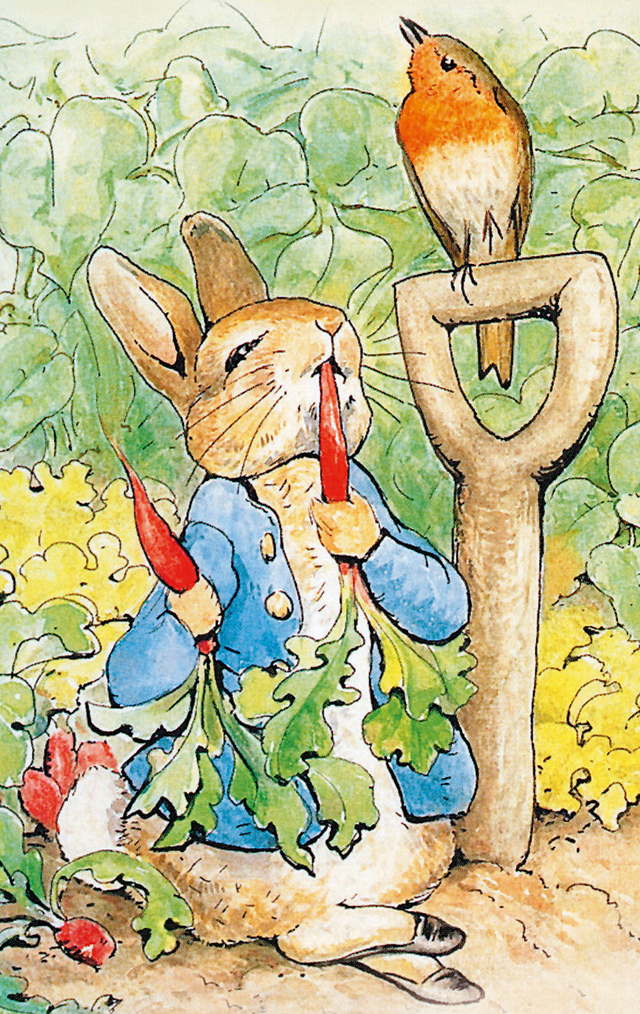

Potter’s characters such as Peter Rabbit and Mrs Tiggywinkle are as instantly recognisable to British readers as The Queen’s head on a postage stamp or the label on a Marmite jar.

She is one of many authors who choose to illustrate their own work – something which, at its best, results in a complete integration of text and image, as seen, for example, in The Tale of Mr Jeremy Fisher. In some illustrated books for younger children, such as Judith Kerr’s The Tiger Who Came to Tea or the work of Emma Chichester Clark, story and illustration are of equal impact and importance.

– – – –

Peggy Fortnum

Peggy Fortnum created first illustrations to Michael Bond’s ‘Paddington Bear’ stories in 1958 and went on to illustrate three more of the author’s story collections. Her deft line drawings suggest action, speed and anarchy – in other words, a perfect illustration of the chaos that the well-meaning bear invariably leaves in his wake. Despite television and cinema incarnations, it is Fortnum’s slightly tatty, harassed and perpetually bemused traveller who remains the marmalade-loving bear from Peru for most readers.

– – – –

Sir Quentin Blake

Best known for his work illustrating Roald Dahl’s stories, Sir Quentin’s work – with its vigorous line and boldly handled colouring – thrillingly captures the ambivalence of Dahl’s fiction, with its dark humour and occasionally riotous abandon.

– – – – –

Ronald Searle

Anarchy – and occasionally menace – are qualities that frequently characterise illustrations to children’s stories. Appropriately, suggestions of the former dominate Ronald Searle’s vision of Geoffrey Willans’s ‘Molesworth’ stories, set at St Custard’s prep school and first published between 1953 and 1958.

Molesworth’s exceptionally bad behaviour acquires an added layer of charisma in Searle’s ebullient images: the excitement of Molesworth’s haplessness reassures readers of his ultimate success.

– – – – –

Edward Ardizzione

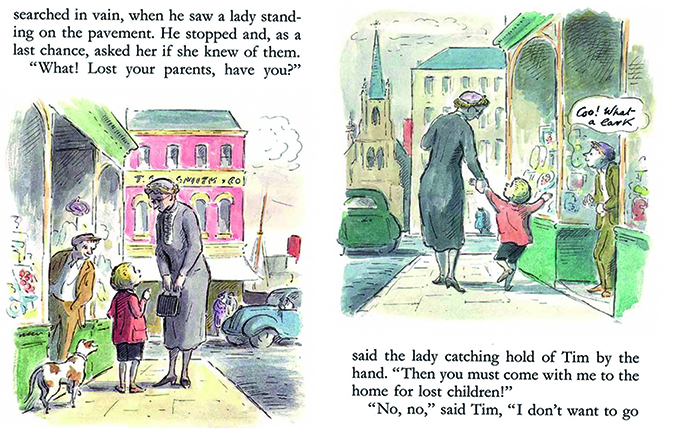

Ardizzone’s watercolour illustrations to his ‘Little Tim’ series of children’s books, first published in 1936, provoke nostalgia not so much for one’s own childhood as for a vanished world of safe assumptions, social cohesion and unspoilt country. Like Eileen Soper’s illustrations to Enid Blyton’s ‘Famous Five’ stories, it has maintained an appealingly inter-World War quality into the 1950s and beyond.

– – – – –

Kate Greenaway, Walter Crane and Randolph Caldecott

These pioneering illustrators produced work for a range of children’s books, in each case including collections of rhymes and nursery rhymes. Although their particular styles differ, each successfully produced artwork that apparently ‘reinvented’ traditional rhymes for their first audiences, as well as maximising the potential of chromoxylography for reproducing the intricacies of complex, many coloured line-and-wash images.

Kate Greenaway

Walter Crane

Randolph Caldecott

– – – – –