In a dimple-covered Norfolk landscape, Britain's only open Neolithic flint mine is still revealing its secrets

Originally in use at the same time the Stonehenge boulders were raised, the mines at Grime's Graves are the oldest manmade underground space in England.

The oldest manmade underground space in England, which dates from the time the Stonehenge boulders were raised, has been reimagined for its 2024 opening.

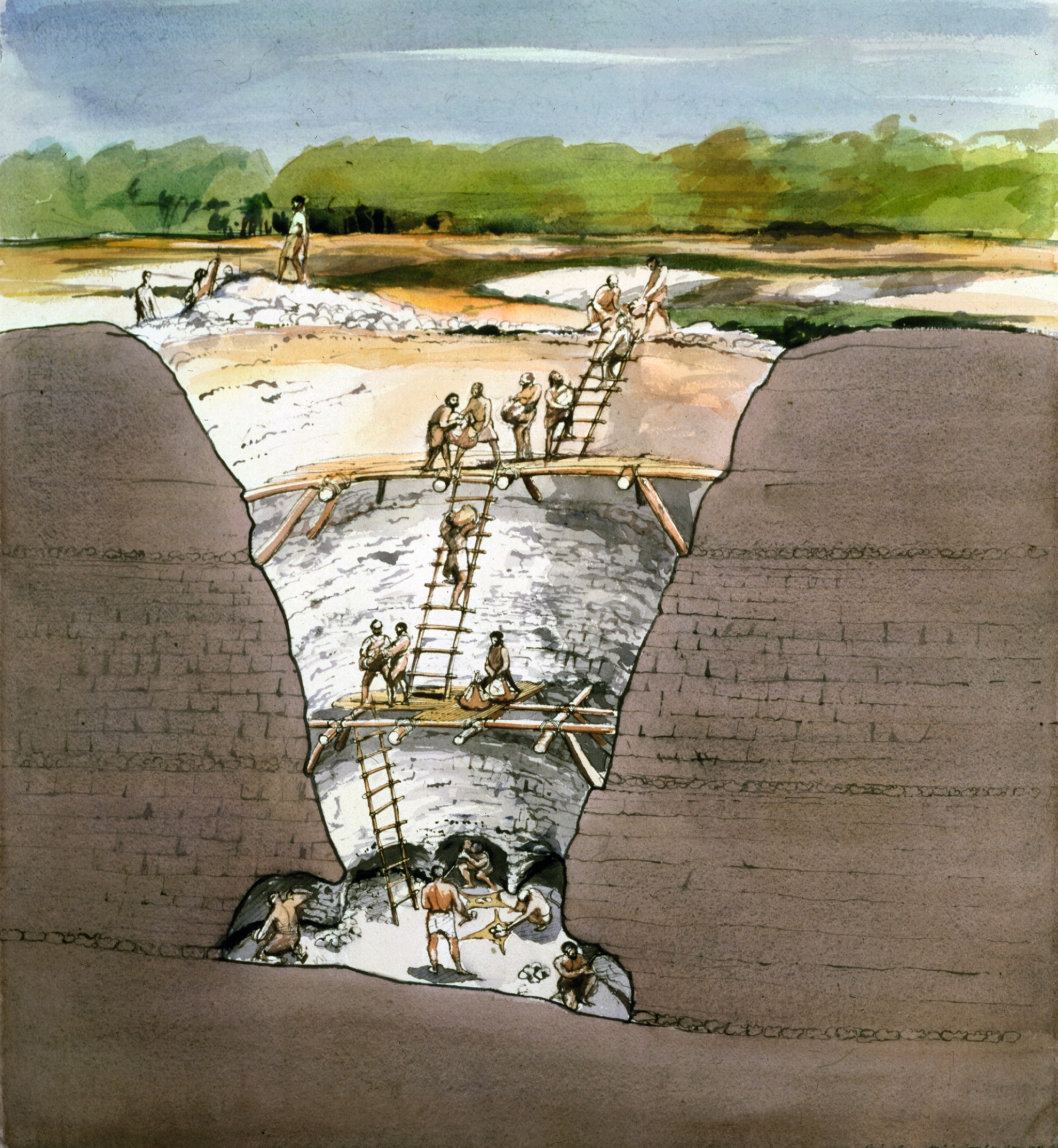

Within Breckland grass heath, where rare wild pansies, yellow kidney vetch and wild thyme grow, the strange, lumpy landscape of Grime’s Graves in Norfolk — or Grim’s Graves as the Anglo-Saxons called it, believing it to the burial place of the god Wōden or Grim — conceals a labyrinth of subterranean tunnels across 430 mine shafts, some up to 13 metres (43ft) deep, in which men, women and even children would mine high-value, jet-black flint.

'What I find remarkable is the deep understanding the miners had of their environment,' says Jennifer Wexler, English Heritage's properties historian. 'The mines are a feat of great engineering skill, showing sophisticated geological knowledge of the earth.'

'The site was in use at the same time that Neolithic people were transforming their world on a massive scale and building impressive monuments across the British Isles, such as Stonehenge and Avebury.'

Formed many millions of years ago by the debris of sea creatures on what was then an ocean bed and known as the ‘Swiss Army Knife’ of the Neolithic world, flint was harnessed for its versatility, durability and spiritual properties to make tools, weapons and ceremonial objects; it’s thought that the flint from Grime’s Graves was particularly high quality.

The 4,500-year-old site reopened at the end of April and visitors can now descend easily, from a new structure atop a mineshaft, straight down to a level 30ft below, where a film projection on visibly hacked-at walls tells the story of the people who laboured there.

‘It was not until 1868–70, when one of the pits was excavated, that this was even identified as a Neolithic flint mine. To this day, most of the more than 400 pits remain untouched and geophysical surveys suggest that the mines covered a much greater area, so we are getting a tantalising glimpse into place full of hidden mystery,’ adds Ms Wexler.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

'It's brilliant that visitors will be able to see a few of the remarkable objects we have recently excavated in our new exhibition and then descend deep underground to have this totally otherworldly experience.'

Credit: John F Scott/Getty Images

Getting a wiggle on: How 're-wiggling' our rivers can save our countryside

For more than a century, rivers have been straightened. Now, however, meandering projects are going on across the country to

Stonehenge, Avebury and the stone circles of Britain, with Professor Vicki Cummings

One of Britain's top experts on stone circles, Professor Vicki Cummings, joins the Country Life podcast.

'Where birds and a wild Englishman roamed': The world's first nature reserve granted listed status

Waterton Park in West Yorkshire was the 'prototype for the modern nature reserve', and has been rewarded by Historic England

Credit: James Brittain/Getty Images

Leading museums and attractions slowly returning to pre-Pandemic levels, with London leading the way

According to the Association of Leading Visitor Attractions, visitor numbers were up by 19% last year.

Annunciata is director of contemporary art gallery TIN MAN ART and an award-winning journalist specialising in art, culture and property. Previously, she was Country Life’s News & Property Editor. Before that, she worked at The Sunday Times Travel Magazine, researched for a historical biographer and co-founded a literary, art and music festival in Oxfordshire. Lancashire-born, she lives in Hampshire with a husband, two daughters and a mischievous pug.

-

'Love, desire, faith, passion, intimacy, God, spiritual consciousness, curiosity and adventure': The world of Stanley Spencer, a very English visionary

'Love, desire, faith, passion, intimacy, God, spiritual consciousness, curiosity and adventure': The world of Stanley Spencer, a very English visionaryStanley Spencer’s talent for seeing the spiritual in the everyday, his stirring sense for the wonder of Nature and his love for the landscapes of Berkshire and Suffolk shaped his art, as Matthew Dennison reveals.

-

Waldorf Astoria New York review: The Midtown hotel where Frank Sinatra once partied and the salad of the same name was invented emerges from a decade-long renovation

Waldorf Astoria New York review: The Midtown hotel where Frank Sinatra once partied and the salad of the same name was invented emerges from a decade-long renovationOwen Holmes checks into the Waldorf Astoria New York hotel.