As a new exhibition opens at the Royal Academy on modern art and gardens, Tim Richardson explores Monet’s interest in horticulture

A major exhibition at the Royal Academy (RA), ‘Painting the Modern Garden’, provides an opportunity to reflect on the relationship between gardens and art or, perhaps more specifically, given Claude Monet’s prowess as a gardener, the links between horticulture and art. Focusing on artists working between 1870 and 1930, the show shines a light on lesser-known painters such as Joaquín Sorolla and Max Liebermann, while also reminding us of the importance of plants and gardens to such figures as Emil Nolde, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky and Pierre Bonnard. Monet remains the central figure, however.

It is difficult to generalise about the importance of the garden theme to such artists, because every painter utilises it in a different manner, whether as a fantastical or mystical setting (Klee, Vuillard), as an atmospheric domestic space charged with emotion (Morisot, Bonnard), as social comment (Pissarro, Seurat) or as a veritable festival of form, colour and light (Kandinsky, Dufy).

The variousness of artistic interpretation is the reason why the RA exhibition, which has been curated along traditional art-historical lines, as set out in such books as Roy Strong’s The Artist and the Garden (2000), can have no central thesis. As Bonnard observed, ‘the true paradises are the paradises we have lost’, implying that the garden in all its fragile mutability can never be pinned down. This Proustian delicacy emerges as one of the garden’s most compelling characteristics.

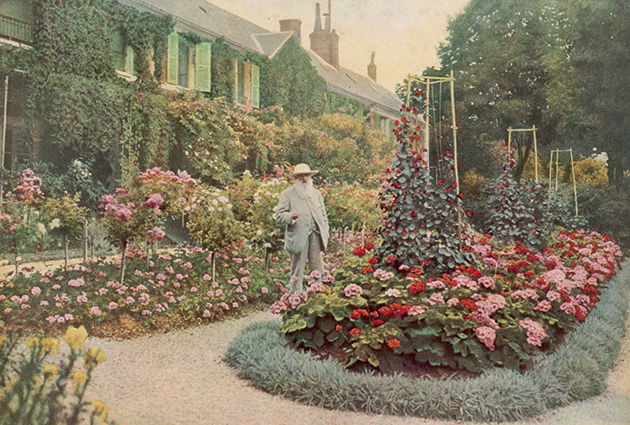

From an art-historical perspective, painters’ gardens are habitually characterised as ‘artistic laboratories’ for experimentation with colour and form, rather than as works of art in their own right created by horticultural means. Monet, however, once described the garden at Giverny as ‘my most beautiful work of art’ and Matisse’s garden at Issy-les-Moulineaux could be viewed in the same light. However, the attitude still besets writing about ‘art gardens’, such as Ian Hamilton Finlay’s Little Sparta, near Edinburgh, which even now tends to be described by art critics as an agglomeration of sculpture as opposed to a single artistic entity.

Horticulture was not a retirement hobby for Monet, who gardened at every property he rented or owned from the 1860s when he was in his twenties until his death in 1926. Manet painted Monet and his family in the garden at Argenteuil in 1874, with the blue-shirted young painter bending to examine some red flowers, a watering can at his side. (According to Monet, Renoir turned up that same afternoon and began painting his own version of the scene, much to Manet’s chagrin.)

From the outset, gardens were an important theme for the painters who came to be known as the Impressionists, with Renoir even famously depicting Monet at his easel in the garden in 1873. Gardens were attractive partly because they embodied an outdoors aesthetic with overtones of the honest hard work of the proletariat. They were redolent of a kind of independent-minded, anti-establishment domesticity, countrified as opposed to urban, and were an anti-heroic gesture against what was seen as the neo-Classical posturing of earlier generations of French artists.

The garb of the gardener heavy boots and smock became part of the uniform of the avant-garde; Monet, and later Matisse, were among those who relished playing the anti-chic part of gardener, receiving guests in their gardening clothes and making them gifts of plants as they departed. Octave Mirbeau, an art critic and gardening friend of Monet, reported discovering Monet in his garden, ‘his arms black with compost’.

But it was by no means all show. Monet became ever more committed to his garden after 1880, when he was able to purchase the farm-house he had been renting at Giverny.

He employed a number of gardeners from the outset, ordered seeds and plants from leading nurseries in France and England and made a regular habit of visiting the rose trials at Bagatelle (he was an early adopter of the climbing rose American Pillar, which went on to become a garden standby).

As well as Mirbeau, Monet’s chief horticultural friend was his fellow artist and Argenteuil neighbour Gustave Caillebotte, who created a serious garden, including an important orchid collection in his large greenhouse. Giverny was to become a nexus of horticultural interest for Monet’s contemporaries. Among the early visitors who pursued the garden theme in painting themselves were Morisot and Sargent, with Cézanne, Matisse and Bonnard coming later.

None was as horticulturally advanced as Monet, whose work might also be understood in the light of the influence of two great garden stylists of the period: Gertrude Jekyll and William Robinson. We know that Monet subscribed to Country Life, and therefore Jekyll’s writings, after 1897, but he was also aware of Robinson’s prescriptions from the 1880s at least.

As the author of The Wild Garden (1870) and The English Flower Garden (1883), Robinson was the most influential garden commentator in Europe, operating at the cutting edge of garden style. As founding editor of The Garden magazine, he published Jekyll’s articles from the mid 1870s onwards, just as Monet was getting serious about horticulture.

Robinson and Jekyll presented different but complementary approaches to gardening. Jekyll was especially interested in colour theory in planting, as derived from a celebrated manual by Michel Eugène Chevreul (1786–1889), which set out a ‘colour wheel’ of primary and complementary colours. Robinson created a vogue for the naturalistic ‘wild garden’ in opposition to the formal carpet-bedding

of the Victorian period, although he was certainly not averse to botanical exotica in the right setting. Monet’s garden betrays the influence of both, transformed by his own instinctive flair.

Jekyll promoted the idea of the garden as a series of ‘pictures’, an idea perhaps derived from her background as a painter. As she wrote in an 1882 issue of The Garden: ‘In setting a garden we are painting a picture, only it is a picture of hundreds of feet or yards instead of so many inches, painted with living flowers and seen by open daylight.’

Jekyll was subject to the same influences as the French Impressionists at about the same time. In her first book, Wood and Garden (1899), she remembered an incident from her painting days as she studied a white horse from the life: ‘On looking up I was amazed by the sight of a blue horse with a large orange spot on his flank. I never can forget the sudden shock of that strangely coloured apparition.’ This sounds almost more Fauvist than Impressionist, but Jekyll is writing about the 1870s, when she came under the influence of the proto-Impressionist English painter Hercules Brabazon Brabazon (1821–1906).

Monet and Jekyll were equally obsessed with colour effects in the garden, especially powerful contrasts. Monet liked vivid reds offset by green foliage, provided by the massed nasturtiums along his boundary fence, for example, or cool blues set against flaming yellows, such as the salvia and sunflowers along his Grande Allée. They were united, however, in their suspicion of an over-reliance on Chevreul’s ‘colour wheel’: Jekyll warned that, ‘the “laws” of colour laid out by writers on decoration is a waste of time’ and Monet propounded an instinctive, painterly response.

There were also salient differences between their approaches to gardening. Monet’s effects were more broad-brush, with a reliance on serried ranks of identical bright flowers arranged in long bands, an idea that was arguably derived in part from an awareness of the French vernacular gardening tradition, where annual flowers are sown in lines among vegetables.

Jekyll pursued an elaborated version of the English cottage-garden tradition, resulting in a more embroidered effect, although she could also revel in colour for its own sake, as with the pansy display and aster borders in her own garden at Munstead Wood.

There were ramifications for painting as a result of these differing approaches. Ironically perhaps, given his interest in newly hybridised flower forms, Monet’s depictions of plants are always massed and generalised, emphasising the bubbling appearance of, for example, groups of irises, the translucent flower petals of cosmos, hollyhocks and dahlias or the massed effect of delicate white-flowered plants, such as gypsophila and forget-me-nots. The plants add strong dynamism to his garden scenes, which is perhaps why, as time went on, he rarely included human subjects in his garden paintings.

Monet’s planting schemes did not function as narratives composed of chromatic episodes to be experienced sequentially on the move, as Jekyll’s borders did; rather, they burst on the retina in a single explosive vision perhaps more useful as material for the painter. By contrast, British garden painters, such as Alfred Parsons and Beatrice Parsons, attempted to capture the complexity of planting style and individual flowers with mixed results.

Monet was one of very few gardeners internationally who could work with the chromatic exactitude demanded by Jekyll. Robinson’s influence, as disseminated in the work of Édouard André in France and Alfred Lichtwark in Germany, was far deeper and wider. The engravings by Alfred Parsons in later editions of The Wild Garden (which Monet knew) capture something of the garden atmosphere Robinson was espousing, with star plants (some of them common wildflowers) expressing themselves in an unburdened and apparently wholly naturalistic manner.

There was no question of formal flowerbeds in the Victorian tradition, but, at the same time, the Robinson look demanded a certain poise. Monet reflected it in his paintings of the period, such as Young Girls in a Bed of Dahlias (1875), which captures a Robinsonian wild-garden atmosphere. The garden scenes of Monet’s contemporaries, notably Renoir, which resemble untended wildernesses, do not evince a similar level of understanding, which helps to explain why, at Monet’s death, his friend the nurseryman Georges Truffaut mused that the painter was ‘one of the first to show his compatriots that it isn’t only the English who know how to use flowers as a decorative motif’.

‘Painting the Modern Garden: Monet to Matisse’ is at the RA, London W1, from January 30 until April 20 (020–7300 8090; www.royalacademy.org.uk). Tim Richardson is chairing a discussion at the RA on March 4, ‘A Work of Art: Colour and the Garden’

Giverny and Gravetye: some parallels

There is no evidence that Monet and Robinson ever met or corresponded, yet there are strong similarities between the artist’s garden and Gravetye Manor, the Sussex house and garden acquired by Robinson in 1884, just a year after Monet had moved to Giverny. Both featured relatively formal flowerbeds near the house, dominated by large numbers of single-species flowers.

Additionally, both came to include a discrete garden area at one remove from the house and its immediate vicinity. At Giverny, this was the celebrated water garden, with water lilies and ‘Japanese’ bridge, sited on a separate piece of land across a road; at Gravetye, it is the wild woodland garden, uphill and removed from the main garden area, beyond a large formal lawn.

Robinson even developed an obsession with water lilies (right), sourcing specimens from the breeder used by Monet, Latour-Marliac. He viewed his horticultural endeavour as artistic and invited artists to live at Gravetye so that they might paint the garden.