Imagine you're cut off in a far-off land. What longings would be uppermost in your mind? Here we celebrate those aspects of life that make our islands distinct and beguiling.

1. The white cliffs of Dover

‘There’ll be bluebirds over the white cliffs of Dover,’ sang Vera Lynn in 1942 in the song that came to represent doughty British spirit at a time when Hitler had conquered much of Europe and unleashed a terrifying bombing campaign on our cities. However, the mighty chalk cliffs, which tower some 350ft above the Straits of Dover, have long been a symbol of ‘Old Blighty’ as they face towards France over the narrowest section of the English Channel. For many travellers, catching a glimpse of them from a plane window or a ferry deck is a sign that they are truly home.

‘The cliffs of England stand, Glimmering and vast’

(Dover Beach, Matthew Arnold)

2. Exmoor pony

The ponies that roam Exmoor’s heathery hills are proudly pure bred. The endearing uniformity of their mealy muzzles, bulging ‘toad’ eyes, chubby furry bodies and specially adapted tail with ‘snow chute’ is testament to assiduous protection of the gene pool by some 10 herd owners since numbers shrank after the Second World War. Every autumn, farmers round up their ponies—tricky, as this Thelwell-ish native has a mind of its own—for inspection by The Exmoor Pony Society. The enchanting local distinctiveness of Britain’s fields and farmlands, and the integrity of our native breeds, owes everything to such groups, plus the admirable Rare Breeds Survival Trust started by farmers 40 years ago.

‘The coming generations will have good reason to call us unfaithful

stewards if when we are gone there are no little horses on the Exmoor hills’

(Mary Etherington, 1947)

It’s a beautifully designed object with an extraordinary function. Developed by novel- ist Anthony Trollope when he worked as a Surveyor’s Clerk for the Post Office, they were a natural product of the penny post, which opened up the universal postal system to almost everyone in Britain. Their first trial was in 1853 on the Channel Islands. Originally green, they were painted red from 1874 as people had difficulty finding them.

‘[England] is somehow bound up with solid breakfasts and gloomy

Sundays… green fields and red pillar-boxes’

(George Orwell)

4. Wolf Hall

Right now, you could be forgiven for thinking that the American TV schedule originated in Britain. Hit new show House of Cards is an adaptation of the superior BBC original. Broadchurch was so successful that they had a go at making an American version of it (which failed to capture the claustrophobic atmos-phere of a small coastal town). It was recently announced that Doctor Who and Sherlock will be shown in the USA at the same time as in the UK to stop piracy. And Wolf Hall is finding an audience among fans of Game of Thrones. It seems that almost every show features at least one British actor hoping to achieve the same acclaim as Dominic West, Damien Lewis and Hugh Laurie. So forget those expensive boxsets, put your feet up, watch our own television and be ahead of the crowd.

‘Drama is life with the dull bits cut out’

(Alfred Hitchcock)

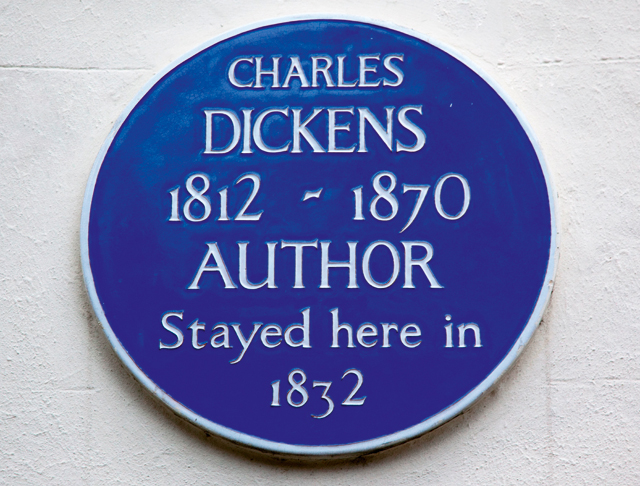

5. Blue plaque

Once you know what a Blue Plaque is, it’s impossible to pass one without stopping to read it. These distinctive ceramic discs record where celebrated individuals from the past lived or worked. The first commemorative plaque of this kind—to Lord Byron—appeared in London in 1867. Subsequently, the idea was taken up by London County Council in 1901, but the scheme is presently managed by English Heritage. In the meantime, this simple idea has been copied across Britain and the world.

‘To look backward for a while is to refresh the eye, to restore it,

and to render it the more fit for its prime function of looking forward’

(The Roadmender, Margaret Fairless Barber)

6. Choristers

Is there any sweeter sound on Earth— effortless, pure and full—than that of the boy trebles of a cathedral choir taking flight? Whatever your religious inclination, this is musical performance of the highest calibre, balm for the soul and usually free. Get your child into a cathedral-choir school, and he or she will have an unrivalled education that brings intellectual stimulation, confidence and friendship.

Britain has the world’s strongest choral tradition, nurtured successively by medieval monks, royal composers Tallis, Byrd and Handel, who wrote Messiah in London, and conductors David Willcocks, John Eliot Gardiner, the late Richard Hickox and the engaging Gareth Malone, who has persuaded the entire country that singing rocks.

‘[The] sound is quintessentially English, with a purity in the way the boys in particular sing, which could become hooty but never does’

(Conductor Sir Andrew Davis, a former King’s Organ Scholar, Cambridge)

7. Market cross

The right to hold a market was once a jealously guarded privilege. It was also a key to commercial prosperity, as the fine central market squares in towns and villages across the country testify. These all originally had—or have had re-created—a stone cross that marked the site of the medieval market. Whether on market day or not, these remain an important centrepiece to the town.

‘Ride a cock-horse to Banbury Cross,

To see a fine lady upon a white horse;

With rings on her fingers and bells on her toes,

She shall have music wherever she goes’

8. Top hat

The Royal Enclosure at Royal Ascot represents the highlight of the Season and it’s where men are required to wear a top hat, preferably a proper tall, silk one. The English Season has evolved from our love of horse racing and the development of other games that turned into major sporting events centred on the glorious midsummer season. Wimbledon, Lord’s, Henley, Goodwood and Glyndebourne all evoke dressing up, benign sunny weather, picnics and a douceur de vivre that is compressed into a few precious summer months.

The Royal Enclosure at Royal Ascot represents the highlight of the Season and it’s where men are required to wear a top hat, preferably a proper tall, silk one. The English Season has evolved from our love of horse racing and the development of other games that turned into major sporting events centred on the glorious midsummer season. Wimbledon, Lord’s, Henley, Goodwood and Glyndebourne all evoke dressing up, benign sunny weather, picnics and a douceur de vivre that is compressed into a few precious summer months.

Glorious Goodwood: ‘a garden party with racing tacked on’

(Edward Vll)

9. Bluebells

Nearly half of all common bluebells are found in the British Isles, the distinct purple haze carpeting ancient woodland floors evoking the richness and subtlety of our wild flora. The Botanical Society of the British Isles has the bluebell as its symbol, but other wildflowers evince equal adoration, such as the lily of the valley with its scented flowers, cow parsley foaming along road verges and the wild daffodils that so enchanted Wordsworth.

‘Like the blue sky, breaking up through the earth’

(Alfred, Lord Tennyson)

10. The sporran

From a belted leather pouch to a fur-tassled beaver mask suspended from a silver cantle, the sporran (Gaelic sporan—purse) is the best-known accoutrement of the kilt, that instantly recognisable badge of Scottish identity. Originally worn by Highlanders at all levels of society, the kilt and the tartan from which it is made have a long and complex history freighted with issues of status, image and political allegiance. Institutionalised by the British Army and romanticised by Walter Scott and Queen Victoria, Highland regalia became increasingly associated with formal dress—a flamboyant plumage accessorised with sporran, sgian dubh, claymore, powderhorn, shoulder plaid, ornate brooch, belt buckle and Glengarry bonnet. Today, the kilt has become fashionable again, reinterpreted by fashionistas and urban youth to appeal to a broader circle, so that, once again, it transcends all class barriers and social conventions.

‘Where’s the coward that would not dare to fight for such a land?’

(Sir Walter Scott)

11. Fingerposts

The fingerposts that adorned Britain’s roads are charming and distinctive local markers. They are also remarkable survivals. Many were taken down in the Second World War (some of our placenames could only have confused the enemy rather than helped it) and those that did remain came under threat in the 1960s from the edict to standardise road signage. However, the success of the 2005 A Future for Fingerposts campaign means that new ones to match the original designs are sprouting up all over the place.

‘Not all those who wander are lost’

(J. R. R. Tolkien)

12. Penicillin

Discovered by Alexander Fleming, the son of an Ayrshire farmer, in 1928, penicillin broke new ground because, by the time it was being mass-produced in the 1940s, it was among the first drugs to be truly effective against many serious diseases. Fleming wasn’t Britain’s only medical pioneer. In the late 1950s, fellow Scotsman Sir James Black developed the beta blocker Propanolol, which is credited with saving the lives of millions of heart-disease sufferers, as well as Cimetidine, the first modern ulcer drug, and Rosalind Franklin made great strides in the study of DNA. In 1972, Sir Godfrey Hounsfield invented the CAT scanner and, in 1978, Patrick Steptoe and Robert Edwards carried out the first successful IVF procedure.

‘Thanks to penicillin he will come home!’

(Second World War poster)

13. Wellington boot

We have Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington, to thank for Britain’s treasured wellie. Fresh from his defeat of Napoleon in 1815, the Duke deemed his current boots uncomfortable and asked his personal shoemaker to tweak the design of his military Hessian pair. The Wellington boot was originally made from leather until the mid 19th century, when a revolutionary rubber process was discovered. The boot meant farmers could now work a day outside with the luxury of dry feet. Still a farmer’s best friend, modernisation and the rainbow of colours available have ensured it also enjoys a cult fashion status, with the rubber boots now equally at home, caked in mud, at Glastonbury.

‘There’s man all over for you, blaming on his boots the faults of his feet’

(Samuel Beckett)

14. Land Rover

The original Land Rover was launched in 1948 and even now, as part of the Indian-owned Tata group, remains an icon of British engineering, solidity and style. The early colour choice was dictated by military- surplus supplies of aircraft cockpit paint—various shades of light green. The new generation—such as Range Rover, Evoque and Discovery— is a testament to an enduring brand whose sales of technologically advanced cross-country vehicles are growing even while some of those original postwar Series 1 models are still on the road.

‘The idea of wilderness needs no defence, it only needs defenders’

(Edward Abbey)

15. Swaine Adeney Brigg umbrella

The wooden parts of these beautifully crafted items can be made in oak, maple and hickory and the canopies were traditionally fashioned in silk, but it’s what they protect us from that has made our land green and glorious. Where would our small talk come from if we didn’t have the weather to discuss and how would our landscape look so verdant without the rain?

‘The English winter—ending in July, to recommence in August’

(Don Juan, Lord Byron)

16. Roberts radio

The Archers, Just a Minute, Today, Book at Bedtime, Test Match Special, Desert Island Discs: there is so much to entertain and inform on radio. The number of listeners is holding its own in the digital age and podcasts enable people to take their favourite programmes with them on trains and tractors. What better model is there to represent the golden age of radio and its renaissance than the Roberts, from a company that has been making beautiful radios for more than 80 years?

The Archers, Just a Minute, Today, Book at Bedtime, Test Match Special, Desert Island Discs: there is so much to entertain and inform on radio. The number of listeners is holding its own in the digital age and podcasts enable people to take their favourite programmes with them on trains and tractors. What better model is there to represent the golden age of radio and its renaissance than the Roberts, from a company that has been making beautiful radios for more than 80 years?

‘Radio is like bread and butter to people; they will never do without it’

(Harry Roberts)

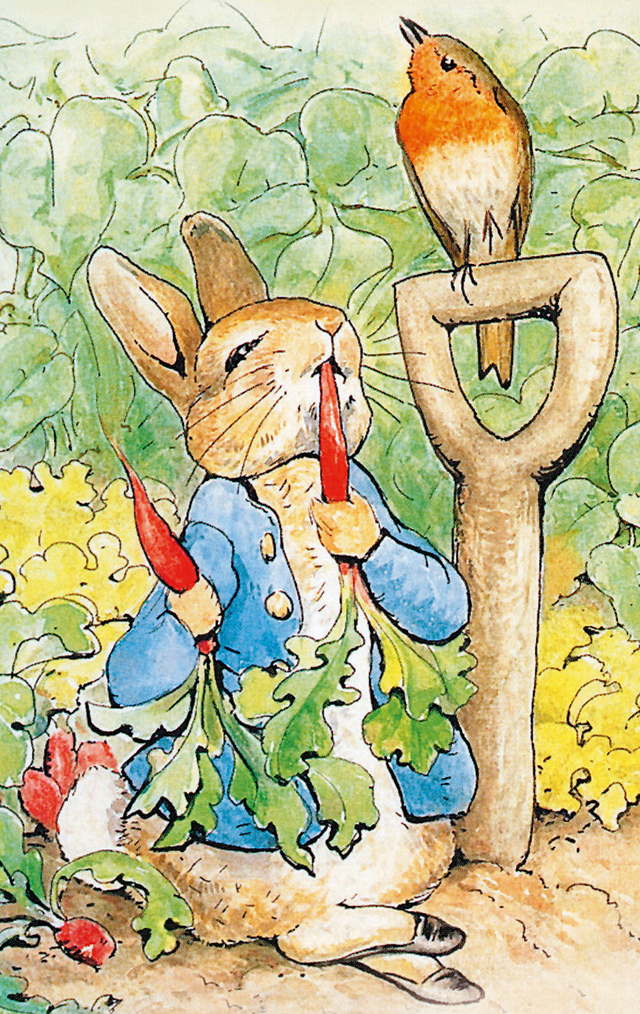

17. Children’s literature

Some 150 years ago, Britain fell in love with the story of a little girl who fell down a rabbit hole; it’s inspired a host of film, television and stage adaptations ever since. Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, like so many British children’s books, has become integral to our national identity as we continue to produce some of the finest children’s authors in the world. We can lay claim to A. A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh, Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Peter Rabbit, Roald Dahl’s BFG, J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings and Enid Blyton’s Famous Five. With a nudge of help from the ‘Harry Potter’ phenomenon and authors such as Michael Morpurgo, Julia Donaldson and Anthony Horowitz, reading is the height of fashion among teenagers today. From Neverland to Narnia, the fantastical and unlimited imagination of British children’s literature continues to flourish.

‘You’re entirely bonkers. But I’ll tell you a secret. All the best people are’

(Lewis Carroll)

18. Glastonbury

Glastonbury began in 1970 when 1,500 tickets were sold for £1 to include ‘free milk from the farm’. It’s now the most iconic music festival in the world—its 135,000 tickets are sold out in a matter of minutes and the announcement of the headline act is front-page news. At music festivals through- out the UK, thousands gather every year to stand in a field to sway to their favourite songs. Like tennis and Pimm’s, music festivals have become a hallmark of summer and weather is never an issue.

‘And hand in hand, on the edge of the sand,/They danced by the light of the moon’

(‘The Owl and the Pussycat’, Edward Lear)

19. Turner

‘Light is therefore colour,’ said the English painter J. M. W. Turner. The master of colour and light, who could combine the abstract technique of sug- gesting weather and atmosphere with technical mastery of detail—for instance, of the ship’s rigging in this 1838 painting of The Fighting Temeraire being tugged to her last berth—Turner was more than just a topographer; his poetic vision imbued his paintings with emotional depth. In his handling of paint, he anticipated Impressionism. He was said once to have tied himself to a ship’s mast in a storm in order to be able to convey the experience to canvas.

‘I don’t paint so that people will understand me, I paint to show what a particular scene was like’ (J.M.W. Turner)

20. The BBC Proms

How could we bring the Season to a suitable conclusion without the unashamed flurry of patriotism at the Last Night of the Proms? A sea of Union Flags and a roar of throaty exuberance fill the Royal Albert Hall, crowning what Czech conductor Jiri Belohlavek has described as ‘the world’s largest and most democratic music festival’. This year, what started out as The Henry Wood Promenade Concerts—and which soon became affectionately known as The Proms, for short—celebrates its 120th anniversary (July 17–September 12), with a programme encompassing more than 100 concerts of every stripe. The BBC has been running the series since 1927 and now offers many ways to experience a Prom on radio and television so, even if you can’t get there, you can still be a part of the action.

‘I am going to run nightly concerts and train the public by easy stages.

Popular at first, gradually raising the standard’

(Robert Newman, explaining his concept for the Promenade concerts)

21. Country house

The country house has been described as one of the supreme achievements of British culture. Their architecture, art and landscape setting are all a distinctive product of our history, society and climate. There were concerns that the history of the country house had come to an end in the 20th century. All the signs are, however, that old—and some new—buildings of this kind are thriving.

‘The stately Homes of England, How beautiful they stand!/Amidst their tall ancestral trees,

O’er all the pleasant land’

(Felicia Hemans)

22. Badminton Lake

The world’s oldest, most famous cross-country obstacle is a magnet for spectators anticipating a splashy mishap and nervous riders dreading one. It’s no longer the hardest test on the course, but it carries the highest risk of humiliation; photographers crowd its banks, recalling winning shots of Princess Anne emerging dripping, a laughing Capt Mark Phillips draining water from his boots, Mark Todd launching in with only one stirrup and a spectator swimming after a horse. Britain’s status as world leader in eventing owes everything to Badminton. In 1949, the 10th Duke of Beaufort, mortified by the home team’s feeble showing in the 1948 Olympics, started it on his estate to train riders. It became the sport’s ‘Wimbledon’ and embodies our unrivalled tradition of using the great country houses as backdrops.

‘Red [flag] on right, white on left, insanity in the middle’

(Anon)

23. Skilled artisans

From saddlers and silversmiths to forgers, thatchers and sandcasters, there are master craftsmen at work throughout this creative island. Skill sets have waxed and waned with fashions for imports and cheaper alternatives—particularly during the 19th and 20th centuries—but the exciting news is that the appetite for quality craftsmanship made and produced in Britain is on the rise. Buyers of a high-end New York apartment development recently opted to have the handmade joinery for their new kitchens shipped in from Wiltshire, spurning local alternatives. Despite advances in technology, such as 3D printing, nothing can replicate something made by the human hand—if that hand is a British one, then the future for our skilled artisans looks bright.

‘When love and skill work together, expect a masterpiece’

(John Ruskin)

24. Grouse butt

Carefully crafted in neat, round shapes on English and Scottish moorland, and often topped with turf, the grouse butt is part of the furniture on a driven grouse- shooting day. Designed and pos- itioned to give guns the best chance of connecting with the super-charged red grouse whiz- zing over their heads, these stone structures afford guns and loaders some protection from fellow shots as they swing through in pursuit of these most wily of gamebirds. The last truly wild and native gamebird in the British Isles, that sportsmen will pay extraordinary amounts of money to shoot, can often be heard chuckling in the heather as the party departs.

‘Proud August’s past her blooming, In gullies and in cuts/ Down the big winds go booming,

Upon some waiting butts’

(The Red Grouse, Patrick R. Chalmers)

25. Jurassic Coast

Comprising Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous cliffs and documenting 180 million years of geological history, this was England’s first (and only) natural World Heritage Site, stretching 95 miles from east Devon to east Dorset. It has made stars of the natural arch at Durdle Door, the tombolo of Chesil Beach and the limestone folding at Lulworth Cove.

‘I must begin with these stones as the world began’

(Hugh MacDiarmid)

26. English vineyard

Last year, English sparkling wine came second in the medals table of the inaugural Champagne & Sparkling Wine World Championships. The area of vines planted in England and Wales in the past 10 years has more than doubled and even The Queen serves homegrown bubbly at state banquets. The chalky soils around the North and South Downs is prime terroir for this revolution—they’re only about 90 miles north of Champagne and the home of Dom Pérignon and Krug—and warming temperatures are suiting the traditional grapes of Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier. Expect more awards and rising sales.

‘I imagine Hell like this: Italian punctuality, German humour and English wine’

(Peter Ustinov’s putdown no longer works)

27. Wooden sailing dingy

The naval victory of Trafalgar is a matter of national pride, as are the pioneering achievements of Drake and Cook and the records broken by Blyth, Knox-Johnston and MacArthur, but is there a more evocative sig- nal of our maritime heritage than a wooden sailing dinghy with ox-blood sails close-hauled across a saltwater estuary? The myriad local designs, from Chichester scow to Devon yawl, add a picturesque tableau to coves and harbours. Simply mention the words Optimist, Mirror, Fireball, Topper, Feva and Wayfarer, and gene- rations of families who have enjoyed summer fun at Bembridge, Fowey, Bosham or Holkham will find their eyes moistening.

‘It isn’t that life ashore is distasteful to me. But life at sea is better’

(Sir Francis Drake)

28. Mary Rose

On October 11, 1982, an immense salvage operation raised the remains of Mary Rose from the bed of the Solent. The ship, the pride of Henry VIII’s fleet, had foundered suddenly in 1545. Preserved within her wreckage was the most astonishing array of Tudor objects: bows, clothing, skeletons and cannons. This whole collection and the ship itself were revealed to the public in a new museum in 2013 after 35 years in conservation. It’s surely the grandest project of its kind ever undertaken and it offers a revelatory insight into the Tudor world.

‘The wind and the waves are always on the side of the ablest navigator’

(Edmund Gibbon)

29. Worcestershire Sauce

What is ham without Colman’s Mustard or roast beef without horseradish? The history of British condiments is wrapped in myth and misconception. Worcestershire Sauce reportedly came to be in the early 1800s when a former gover- nor of Bengal returned to the county brandishing a recipe for a spicy sauce, which he asked two local chemists—John Lea and Will- iam Perrins—to re-create. Marmite began by the river in Burton-on- Trent as a by-product of the brewing process.

‘Subsequently the happy thought struck someone in the business that the powder might,

in solution, make a good sauce’

(Successful Advertising, Thomas Smith, 1885)

30. Graveyards

Graveyards across the world look very different, each society and culture shaping these settlements of the dead according to their own sensibilities and beliefs. The serene and melancholy beauty so distinctive of the British country churchyard, with its yew trees and tombstones, has long been celebrated. To rest in such tranquil beauty makes even the prospect of death seem a degree less terrible.

‘The grave itself is but a covered bridge, Leading from light to light, through a brief darkness!’

(The Golden Legend, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow)

31. Maps and guide books

In this age of satnav, we’re in danger of losing our knowledge of landscape and topography, of how places are connected and natural features relate. Britain has a proud heritage of cartography dating back to about 1355, its famous Ordnance Survey (OS)—created for military mapping of the Highlands after the ’45—still one of the world’s largest map producers. Today, OS maps are largely the preserve of walkers, rambling having become Britain’s most popular leisure activity, serviced by a network of foot- and bridlepaths and other ancient and modern ways. Regional guidebook publishing, popularised by 19th-century tourists, underwent a revival with the advent of the motor car with series such as the ‘Shell Guides’ and ‘Pevsner’. Now, Britain leads the field in ‘New Nature’ writing, with literary travellers such as Robert Macfarlane sustaining our love of landscape, place names and the great outdoors.

‘They were maps that lived, maps that one could study, frown over, and add to; maps, in short, that really meant something’

(My Family and Other Animals, Gerald Durrell)

32. Film

From the comic assault on the aristocracy in Kind Hearts and Coronets to a different kind of retirement in The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, from 400,000 extras in Gandhi to a doomed romance in Brief Encounter, in films epic and intimate, the British film industry has led the world in every kind of discipline. Our actors have always been acknowledged as the very best, but, thanks to films such as the ‘Harry Potter’ series, our technicians and special-effects craftsmen have finally been recognised for their essential and talented contributions. There’s a lot to celebrate this year with Eddie Redmayne’s Oscar triumph, BBC Films marking 25 successful years and the latest Bond film—will Spectre follow in the record-breaking footsteps of Skyfall, the highest grossing British film ever?

‘I think cinema, movies and magic have always been closely associated.

The very earliest people who made films were magicians

(Francis Ford Coppola)

33. Log fires

Autumn counts the relighting of fires among its delights. Better get the logs piled high, for there’s nothing quite like the welcome of a warm hearth, radiating cosiness and hospitality. Then, there is the delicious aroma that permeates through the house. Connoisseurs insist apple, pear or cherry prunings add extra olfactory nuance and, these days, swift trade is made in small but weighty chunks of olive, whose density ensures a slow burn with faint wafts redolent of the maquis. And, especially in cities, wood-burning stoves are now a fashionable alternative; many of them burn so cleanly that they are approved for use even in designated smokeless zones. Either very well seasoned logs or the modern alternative, kiln-dried, will ensure rapid heat-up and clean burning, adjusted by pleasant fiddling with primary and secondary air vents. Now, that’s warmer.

‘One can enjoy a wood fire worthily only when he warms his thoughts by it as well as his hands and feet’

(Odell Shepard)

34. The Angel of the North

Antony Gormley’s winged figure poised above the A1 at Gateshead can be seen eight miles away, a 66ft steel man with 50-ton wings. Britain’s largest public sculpture is provocative and profound, challenging national conventions of public art while possessing an inner depth and almost spiritual presence in the landscape. A former Turner Prize winner, Mr Gormley is the best known of a new generation of British sculptors whose work builds on the reputation carved out by Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth and Anthony Caro. But The Angel of the North is more than just an artwork: made in a Hartlepool steelworks for Gateshead Council and raised over a coalmine beside a motorway, railway line and football pitch, it has become an arresting symbol of the industrialised North-East and its Newcastle United culture.

‘…dark and true and tender is the North’

(The Princess, Alfred, Lord Tennyson)

35. Monarchy

Don’t listen to all the talk of republicanism from down under— you just have to look at the 20,000 people patiently queuing to pay their respects to Richard III in March to realise that the monarchy is as important to us as ever. Despite Shakespeare’s bleak picture of the king and the condemnation of some historians, we were transfixed by the funeral events and the crowds who lined the routes came from all over the world. Bringing the institution right up to date, the nation has been as enthusiastic to welcome Princess Charlotte as they were her elder brother, George, and The Queen is more popular than ever and will become the longest reigning British monarch in September. It seems that the £500 million tourist income generated by the Royal Family will benefit the nation for a long time to come.

‘Happy and glorious/long to reign over us’

(God Save the Queen)

36. Cathedral spires

Britain’s historic cathedrals are, quite simply, the most widely loved, admired and visited of all our public buildings. In 2012, just over a quarter of the population (11.3 million people) was estimated to have visited a Church of England cathedral in the preceding 12 months. Cathedrals are also great landmarks and the object of intense local pride. The vast spire of Salisbury Cathedral, for example, is a defining symbol of the city and a landmark for miles around.

‘Lector, si monumentum requiris, circumspice’

(‘Reader, if you seek a monument, look around’)

(On Christopher Wren’s tomb in St Paul’s)

37. Theatre

Perhaps Terrence Mann had it right when he said: ‘Movies will make you famous, television will make you rich, but theatre will make you good.’ We can be rightly proud of the rich heritage of our stage—the Americans may be astonished at how willingly British actors will exchange a lucrative film job for the chance to tread the boards in the West End, but few other things can bring them so much professional pride and joy. And that transmits to audiences: London’s theatres saw their biggest audiences ever in 2013. Our appetite to be transported to another world as the curtain goes up remains undiminished and, 400 years after his death, Shakespeare’s work is as powerful and popular as ever. Without it, our culture and our language would be all the poorer.

‘All the world’s a stage,/And all the men and women merely players’

(As You Like It, William Shakespeare)

38. English oak

Our legacy of ancient oaks far exceeds that of any other Western European country. Nearly every lowland parish has at least one that’s more than 250 years old, marking a crossroads, commemorating an accession, sheltering a village seat or standing alone in the middle of a field. Oaks can live for more than 500 years and they become distinct characters well before this, such as the Bound Oak in Berkshire, the Milking Oak in Northamptonshire and Warwickshire’s Baginton Oak, which has a pub named after it.

‘Heart of oak are our ships/ Heart of oak are our men’

(David Garrick)

39. Village pubs

If you want to learn the English language with the British Council, one of the sections of the course will be focused on the village pub and the cultural role it plays. Beginning as inns built along the Roman roads, they became so popular that, in 966, King Edgar limited them to one per village. For centuries, they acted as the social heart of the community, but, since the 1990s, the ‘pie and pint’ culture has been in decline and the ‘gastropub’ born. Those lucky enough to have a pub that acts both as a meeting place for villagers of all ages and walks of life and serves good-quality, locally sourced food are fortunate indeed.

If you want to learn the English language with the British Council, one of the sections of the course will be focused on the village pub and the cultural role it plays. Beginning as inns built along the Roman roads, they became so popular that, in 966, King Edgar limited them to one per village. For centuries, they acted as the social heart of the community, but, since the 1990s, the ‘pie and pint’ culture has been in decline and the ‘gastropub’ born. Those lucky enough to have a pub that acts both as a meeting place for villagers of all ages and walks of life and serves good-quality, locally sourced food are fortunate indeed.

‘Few things are more pleasant than a village graced

with a good church, a good priest and a good pub’

(John Hillaby)

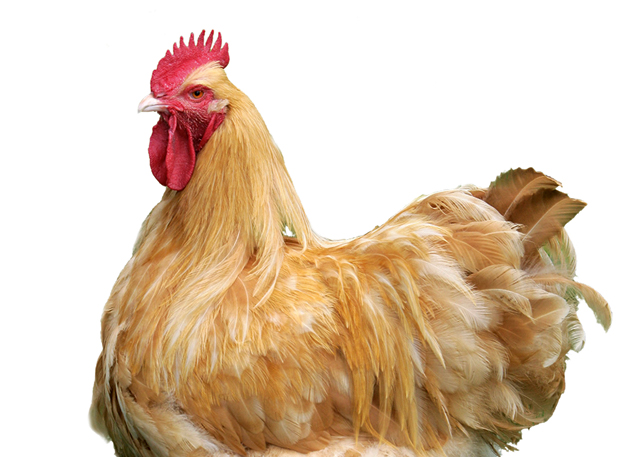

40. Chickens

The fluffy-bottomed Buff Orpington—which also comes in blue, black, white, jubilee, cuckoo and spangled versions—is a chicken with personality, the Marilyn Monroe of the flock and a hen to aspire to. Developed in 1886 by poultry journalist William Cook, a purveyor of fattening powders, in Orpington, Kent, one of its keenest champions was Debo Devonshire, who had them flouncing around Chatsworth, to visitors’ delight. Hens are back in fashion. They’re more amusing company than they’re given credit for and knowledgeable fanciers keep such delightful old breeds as the Scots Dumpy, Marsh Daisy and Speckled Sussex in existence. However, there’s just as much fun—and probably more eggs—to be had with a cheerfully clucking former commercial hybrid.

‘There’s no such thing as equality for hens;

whoever invented the phrase “pecking order” was very clever’

(Deborah Devonshire)

41. William Morris wallpaper

The Arts-and-Crafts Movement was a radical approach to design and production that transformed architecture and the decorative arts in the late 19th century. Reacting to the soulless homogeneity of mechanised production, it promoted traditional methods of hand-craftsmanship as part of a wider, Socialist vision for moral improvement and wholesome living. Key influences included the writings of John Ruskin, the architecture of Philip Webb and the home furnishings company set up by Morris in 1861. Morris & Co fostered unity across the Arts, producing wallpaper, textiles and furniture, as well as metalwork and stained glass, often for buildings designed by like-minded architects for high-minded, Liberal and, paradoxically, rich clients. Arts-and-Crafts designers favoured the bold colours, Gothic style and hand-wrought techniques of medieval craftsmanship and, increasingly, embraced painting, sculpture and book design along with architecture and the decorative arts. Exhibition societies, artisan guilds and craft communities promoted their ideals, which spread internationally and are still a strong influence on makers today.

‘Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful’

(William Morris)

42. Parish-church treasures

In all their astounding variety, our parish churches are monuments to the continuity and history of Christianity in our cities, towns, villages and countryside. These remarkable buildings preserve an extraordinary wealth of artistic riches, from tombs to vestments and stained glass to painting. The place of these much-loved buildings in our lives and landscape must never be taken for granted.

‘The old church tower and garden wall Are black with autumn rain

And dreary winds foreboding call The darkness down again’

(Emily Brontë)

43. Public schools

Eton, Shrewsbury, Harrow, Rugby, Marlborough: nearly everyone will recognise that this is not simply a list of cathedral cities and charming market towns, but some of the greatest schools in the world. Ever since William of Wykeman set up his college for poor scholars in Winchester more than 600 years ago, these schools have been part of national life. Private schools only educate about 7% of the school-age population and annual fees are in excess of £30,000 a year for some. Nearly all, however, provide extensive academic, sports, music and arts scholarships and bursaries. They set a gold standard to which ouruniversal eduction should aspire.

‘That’s the public-school system all over.

They may kick you out, but they never let you down’

(Evelyn Waugh)

44. Rectory

In most villages today, the parson’s house is second only in grandeur to the squire’s, for these buildings were created for clergy who were by birth, education, outlook and pastime, gentlemen. The gradual sale by the Church Commissioners of many of these buildings from the early 20th century onwards has created a large pool of desirable historic, private houses. These are often delightfully set in the shadow of the parish church.

‘We require from buildings two kinds of goodness: first, the doing their practical duty well:

then that they be graceful and pleasing in doing it’

(John Ruskin)

45. Dry-stone walls

Famously, dry-stone walls don’t rely on cement or mortar to hold them together and there is something of the identity of England bound within their framework—hard graft and craftsmanship, geology and the sweeping landscapes they dissect. As well as in the Cotswolds, where there’s thought to be some 4,000 miles of dry-stone walls, these quintessentially British boundaries are generally found wherever stone is abundant or the weather is too rough for hedges, such as the wilds of the Pennines and in Scotland.

‘My hand is upon the stones, and the tale I fain would hear Is of the men who built the walls,

And of the God who made the stones’

(The Song of the Stone Wall, Helen Keller)

46. The English language

Addiction, excitement, generous are just three of the 1,700 words William Shakespeare contributed to the English language. When he was busy creating his masterpieces, modern English was less than 100 years old and consulting a dictionary wasn’t an option—Samuel Johnson’s didn’t emerge until 1755. Our most famous of playwrights not only wrote with a vocabulary approximately four times larger than that of the average person at the time, he also greatly developed the stylistic range and variation of English. Consult any current dictionary, and you’ll find some 600,000 entries reflecting this ever-changing tongue, which is the official language of more than 60 countries.

‘They had nothing in common but the English language’

(Howards End, E. M. Forster)

47. Chalkstreams

Described by Ruskin as ‘trembling and pure, like a body of light’, English chalkstreams are the envy of the world. Some 160 (80%) of the world’s 210 chalk rivers are here. They trickle gently through tranquil countryside, from the becks of the Yorkshire Wolds to the Itchen in Hampshire and the endearing Piddle in Dorset. These mineral-rich, alkaline waters, revered for the superior fly-fishing that can be enjoyed on them, support a host of other wildlife, from kingfishers to otters, and are regarded by countrymen as a liquid national treasure.

‘When trout waved lazy in the clear chalk streams, Glory was in me’

(Sir John Betjeman, writing of the Kennett)

48. The Forth Bridge

Britain’s best-known engineering landmark is a Meccano fantasy of tubular steel latticework that celebrates Victorian engineering and the great railway age. Sponsored by the competing rail companies whose expansion north depended on this strategically vital connection, the 1.6-mile rail bridge between Edinburgh and Fife was designed by Sir John Fowler and Sir Benjamin Baker and opened in 1890. Its single cantilevered span was the longest (since 1917, the second longest) in the world and it has even been adopted as a national colloquialism, ‘painting the Forth Bridge’ being the expression for a never-ending task. The pairing of this behemoth with Freeman Fox & Partners’ Forth Road Bridge of 1964 doubled the significance of the historic North/South Queensferry crossing. Scotland’s Golden Gate is another national icon, soon to be joined by a third: the 1.7-mile Queensferry Crossing, which will become the main vehicular route across the Forth when it opens in 2016.

‘The engineers, with their gigantic works sweep everything before them in this Victorian era’

(Sir Benjamin Baker)

49. Big Ben

Big Ben is properly the name of the largest bell that hangs within the celebrated Victorian clock tower of the palace of Westminster. This singular building, recently renamed the Elizabeth Tower to honour The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee—not to mention the sound of its bells, which play a tune based on a com- position by Handel—has come to symbolise both London and the Houses of Parliament. It’s one of many British buildings that have become instantly recognisable across the globe.

‘I suppose it’s like the ticking crocodile, isn’t it? Time is chasing after all of us’

(Peter Pan, J. M. Barrie)

50. Giant’s Causeway

Throughout the British Isles, the underlying geology is occasionally revealed to form dramatic and distinctive landforms. In few places is the effect so powerful or as curious as this exposed honeycomb of basalt rock that breaks through the cliff-lined coast of Antrim to form the so-called Giant’s Causeway.

‘We meet on the broad pathway of good faith and good will; no advantage shall be taken on either side, but all shall be openness and love’

(William Penn)

51. London Underground map

Had the London Underground publicity department had its way back in 1933, the Tube map as we know it would never have come into being. Initially rejected as being too ‘radical’, Harry Beck’s colourful and, at the time, revolutionary design is now a globally recognised symbol of our capital city. Tube stations famously played a huge role in the Second World War, acting as air-raid shelters, government offices and storage space for British Museum treasures. Today, the Underground delivers more than one billion passengers to 270 stations a year.

‘[The objective is] to enable the traveller so to employ his time, his money and his energy, that he may derive the greatest possible amount of pleasure and instruction from his visit to the greatest city in the modern world’

(London and its Environs: Handbook for Travellers, 1889, Baedeker)

52. Old English side-by-side shotgun

Many of the great English gunmakers first opened their doors in the early 1800s and it’s remarkable that, once these innovative and skilful gunsmiths had perfected the hammer-less, breech-loading side-by-side shotgun in the 1860s, the design has never been bettered. Indeed, the boxlock and sidelock actions that British gunmakers developed then are used in almost all double guns to this day. Traditional makers, such as Purdey & Sons, Westley Richards, Holland & Holland and Boss & Co, still top many leading game shots’ wish lists.

‘The fascination of shooting as a sport depends almost wholly

on whether you are at the right or wrong end of the gun’

(The Adventures of Sally, P. G. Wodehouse)

53. Tea at The Ritz

Ever since Anna Russell, 7th Duchess of Bedford, purportedly complained of ‘having that sinking feeling’ when waiting for her fashionably late dinner, afternoon tea has occupied a sweet space in British hearts. Hymned in song lyrics (The Kinks’ 1967 Afternoon Tea) and preserved by tearooms and hotels across the country, nowhere does it better than The Ritz, a name synonymous with afternoon tea; it’s been served at the hotel since its opening in 1906, a feat surpassed only by Claridge’s. The classic combination of finger sandwiches and sweet pastries served with loose teas has undergone a renaissance: paired with Champagne, accompanied by live music and transformed for all celebratory occasions. The only problem that remains now is what to spread on your scone first—cream or jam?

‘Wouldn’t it be dreadful to live in a country where they didn’t have tea?’

(Noël Coward)

54. British tailoring

Mayfair’s Savile Row and its environs have played host to the most accomplished tailors in the world since the 17th century and a bespoke suit from this hallowed quarter remains the aspiration of any well- dressed gentleman. The oldest tailor of the lot is Ede & Ravenscroft, which dates back to 1689 and still flourishes. A bespoke suit, if well cared for, should last up to 20 years.

‘Th’ embroider’d suit at least he deem’d his prey;/ That suit an unpaid tailor snatched away

(Alexander Pope)

55. The Rolls-Royce

The Rolls-Royce has been a mark of excellence since the conception of the illustrious motor-car company over a lunch in 1904. The very first model, the Silver Ghost, remained in production from 1907 to 1925. Responsible for first-class aero engines (the Merlin powered the Spitfire) as well as motor cars, Rolls-Royce, although now two separate companies, remains a pinnacle of engineering excellence. It’s been based at Goodwood in West Sussex for 12 years. With models such as the Phantom, the Ghost and the Wraith, it’s enjoying a glorious renaissance.

‘Strive for perfection in everything we do. Take the best that exists and make it better.

When it does not exist, design it’

(Henry Royce)

56. The lawn

A fine lawn is considered an English preoccupation, brought to perfection by the twin blessings of a benevolent maritime climate and fertile soils. As a calm, green backdrop to floral borders, beautiful trees or summer recreation, the lawn is without equal. And although its creation was, until the mid 19th century, a labour-intensive exercise only achieved with sharp scythes, modern-day machinery and specialist turf-seed mixtures have put great grass within everybody’s reach. The eternal question is whether stripes are in or infra dig.

‘Nothing is more pleasant to the eye than green grass kept finely shorn’

(Sir Francis Bacon, 1625)

57. Hedgerows

There are currently more than 280,000 miles of hedges in Britain, of which 95,000 miles can be described as ancient or species rich—there’s proof that some date back to the Bronze Age; others have been formed spontaneously as well as being planted by farmers. Usually a mix of shrub and tree species, such as haw- thorn, blackthorn, hazel, ash and oak, interwoven with climbers such as travellers’ joy and honeysuckle, they provide a larder and nesting place for small mammals, insects, butterflies and bats and are a delightfully distinctive feature of our landscape.

‘There’s real life for you… The open road, the dusty highway, the heath, the common, the hedgerows’ (Mr Toad)

58. War memorial

Such was the scale of the casualties in the First World War that virtually every town and village in the country came to possess a permanent monument to its dead. The imperative to create memori- als was further fuelled by the refusal of the authorities to return bodies from military graveyards on the Continent. These ubiquitous memorials to war remain the focus of annual Armistice Day celebrations. They have often also been updated to commemorate the casu- alties of more recent conflicts.

‘They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them’

(For the Fallen, Laurence Binyon)

59. Hunting horn

Since foxhunting originated in Britain in the 17th century, the hunting horn has been an essential tool for huntsmen to communicate with hounds and followers. Its evocative sound—the thrilling ‘Gone Away’, the celebratory ‘doubling the horn’, the sad, tremble of the kill—represents much more than mere practicality. The pageant of hunting continues—more than 300 hunts still meet regularly in most parts of the country.

‘The sound of his horn brought me from my bed’

(D’ye ken John Peel, John Woodcock Graves)

60. Cricket bat

The origins of cricket are lost in the mists of time, but it’s thought to have evolved in Kent and Sussex in the Middle Ages. Now, it’s played predominantly by countries in the Commonwealth, but Lord’s is still considered to be the ‘home of cricket’. Five-day Test matches remain the gold standard of international competition, but the shortened versions of One Day Internationals and T20 have broadened the appeal. At amateur level, the thwack of willow on leather remains one of the summer sounds of the English village.

‘Cricket to us was more than play. It was a worship in the summer sun’

(Edmund Blunden)