Averil King is impressed by a wide-ranging survey of works by Scottish women artists.

Echoes of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s work can be seen in A Girl of the Sixties (about 1900) by Bessie MacNicol.

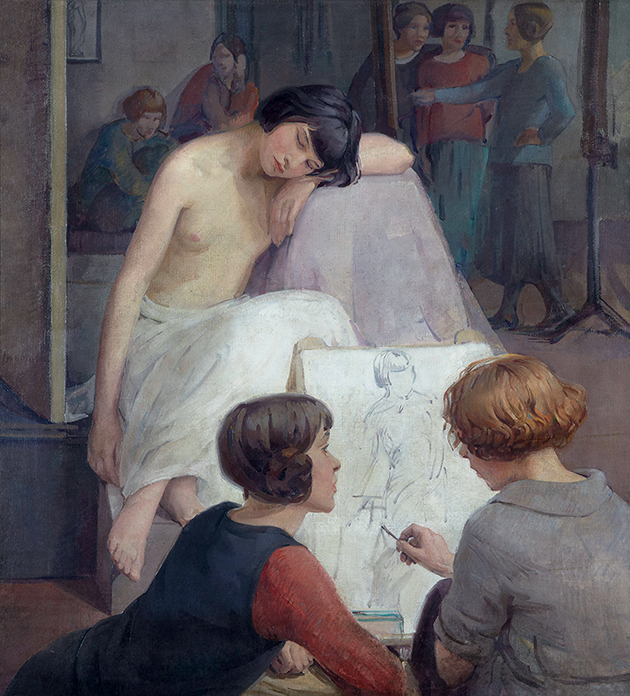

Until the mid 19th century, women who chose the dangerously bohemian path of an artistic career were often advised to paint flowers, but, in 1848, the newly formed Glasgow School of Art admitted female students and, in 1860, London’s Royal Academy (RA) followed suit. Drawing from the live model, however, was another matter, allowed at the RA only from 1893 and not permitted at the Glasgow and Edinburgh Schools of Art until the early 20th century.

Showing paintings and sculptures by artists born in Scotland, and ones who moved there or were of Scottish descent, this exhibition provides a varied and interesting survey of their accomplishments. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the works included reveal a degree of self-absorption, with self-portraits featuring strongly. Images of the artists themselves are testaments to their struggle and commemorate their determination—and their competence. Among the most striking of these is Isabel Brodie Babianska’s Reflection (Self-portrait) of 1939, in which the young artist stands at her easel looking unflinchingly at the viewer. In the gentler self-portrait by Dorothy Carleton Smyth (1921), the artist describes herself against a vivid scarlet background, with a jar of well-used paintbrushes by her side. Smyth had no need to appear rebellious, as she would later be appointed the first woman director of the Glasgow School of Art, but died in 1933, shortly before she could take up the post.

Although not a self-portrait, Bessie MacNicol’s A Girl of the Sixties (about 1900) also features a young woman. Inspired by a theatrical performance in Glasgow, this decorative costume piece has echoes, too, of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s depiction of single female figures. MacNicol’s work was well received and, after her death during her first pregnancy in 1904, James Caw, director of the National Galleries of Scotland, wrote of her as ‘probably the most accomplished lady-artist that Scotland has yet produced’.

Dorothy Johnstone’s Rest Time in the Life Class (1923) allows us an insight into artistic training, perhaps at the Edinburgh College of Art, where she had studied from 1908. Two female students are seen discussing a drawing of the girl who has been modelling for them and is resting behind them. Several wear their hair bobbed, as was then fashionable, but also practical.

In general—with the exception of Johnstone’s Girl with Fruit (1925), in which the young woman eating fruit has a seductive air, and Doris Zinkeisen’s glamorous self-portrait of 1929—the works shown make few concessions to fashion or their subjects’ physical attractions. Several women portrayed wartime subjects: in 1918, Norah Neilson Gray painted a French army hospital and Zinkeisen herself recorded a scene at Belsen concentration camp in 1945.

Many women artists had difficulty reconciling their work with family life and more than one marriage failed for this reason. Nonetheless, there are several exhibits on the subject of motherhood. These include Gertrude Williams’s bronze sculpture Sleeping Mother and Child (1903–5) and Phyllis Mary Bone’s tender Red Deer—Mother and Son (1942), also in bronze, in which the young foal reaches up to nuzzle his mother’s face. One artist facing the dilemma of balancing marriage and career was the talented Cecile Walton, the daughter of one of the Glasgow Boys, Edward Arthur Walton. Both her marriages were doomed to failure. Her portrait of her future first husband and a friend, Eric Robertson and Mary Newbery, painted in 1912, shows them against a backdrop of flowers and is sometimes seen as a rhapsody of summer in the last few years of peacetime.

Walton also excelled at drawing and included in the display in the adjoining library of book illustrations by Scottish women are her appealing colour illustrations for an edition of Hans Christian Andersen’s stories, published in Edinburgh in 1911. Among the comparatively small number of genre paintings are Flora Macdonald Reid’s Fieldworkers (1883), which follows the example of the Glasgow Boys in portraying rural workers at this time, and Mary Cameron’s earthy Les Joueurs (1907), a study of Spanish peasant life in the tradition of Velázquez.

There are just a few dramatic and boldly painted landscapes, including Anne Redpath’s Erbalunga, Corsica (1955) and Joan Eardley’s Catterline in Winter (1963), both painted with a heavy impasto. A more innovative take on the Scottish landscape is provided by Bet Low in her Merge and Emerge of 1961. Brought up along the Clyde Estuary, Low developed an early feeling for the countryside. She later moved to Orkney, where this work, made up entirely of dark-brown shapes merging with stripes of bright yellow-green, was inspired by the island landscape and its atmospheric weather conditions.

‘Modern Scottish Women —Painters and Sculptors 1885–1965’ is at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, until June 26 (www.nationalgalleries.org; 0131–624 6200)